BY G. CONNOR SALTER

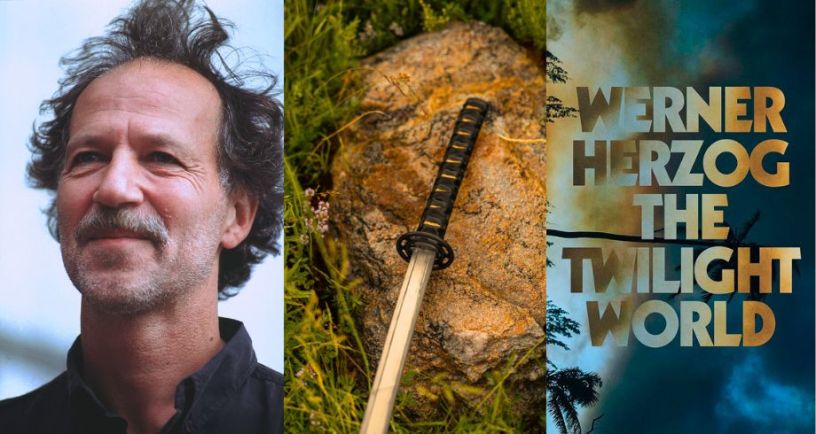

World War II is full of strange stories. One of the strangest stories concerns Hiroo Onada, a Japanese soldier sent to do guerrilla warfare on the Philippines’ Lubang Island… who didn’t stop fighting until 1974. Onada didn’t believe reports the war had ended until adventurer Norio Suzuki found him and connected Onada to his commanding officer, who confirmed the war had stopped in 1945. In 1997, Onada was visited in Tokyo by acclaimed filmmaker Werner Herzog, famous for making movies about individuals on seemingly impossible quests. Their conversations about Onada’s experience form this book, a historical fiction narrative that sticks closely to the facts, while imagining how the experience changed Onada.

This is Herzog’s first novel, and the subject matter is perhaps not surprising. Herzog has made many films about people on seemingly quixotic journeys (most famously Fitzcarraldo). He has also taken a few crazy journeys himself, like walking from Munich to Paris in the winter to visit a dying mentor, as recorded in his book On Walking in Ice. His recent autobiography Every Man For Himself and God Against All (also translated by Hoffman) makes Herzog seem a little more grounded, showing how his early life perhaps conditioned him to try hard things. After growing up in a primitive German village during World War II, only getting shoes in winter and rarely having enough food, most of modern life is easy, and “impossible” movie projects are just projects that require a little extra commitment.

Like previous Herzog books and movies, the story works because these grandiose events are communicated without much ornamentation. The writing style, at least translated by Hoffman, is poetic but not overdone. In that respect, it evokes the style of jungle thrillers like George Steiner’s The Portage of San Cristobal of A.H. Or, to use an example from a Herzog filmmaking contemporary, it may remind readers of the Michael Herr-penned narration in Francis Ford Coppola’s movie Apocalypse Now: strange events described with short words and simple sentence structure. The result makes the characters interesting but never bizarre. Their actions seem unusual but always plausible.

So, it’s well-told, but is it unique? Does it do anything that Herzog doesn’t do better in his movies?

For this reviewer, the answer is yes. For one thing, Herzog avoids the route he sometimes takes when describing this sort of character. He usually makes his quixotic heroes relatable, but some are very clearly fools (particularly the title character in Aguirre, the Wrath of God). Here, Herzog depicts Onada as single-minded, but not foolish. Partly, Herzog does this by giving details on Suzuki, an explorer who said he wanted to find “Lieutenant Onoda, a panda, and the Abominable Snowman, in that order,” and died in 1986 while seeking his third objective. Giving Onada a kindred single-minded spirit shows that this single-minded impulse is more common than some would think.

It also helps that Herzog makes this World War II story into something larger than World War II. The novel mentions several battles, but without any gore, and in a detached way discussing the events after the fact (“character X exploded the docks on Monday,” etc.). Herzog reserves the most details to describe Onada (and initially, some comrades) learning how to live and live out their mission in the jungle. How does one keep military gear rust-free in a perpetually wet environment? How do one’s perceptions (of time, of aging) change when one lives for decades away from other people? Herzog depicts nature as a brutally efficient killing machine that grinds humans down. Thus, Onada’s story becomes more of a war with nature than a war against his American and Filipino targets. The fact he doesn’t win his private war on the West doesn’t make him look ridiculous. The more important fact is how well he survived in the jungle and what he learned from that experience.

That latter point, what Onada learns from the jungle, might be the most intriguing element in this book. In the past, Herzog has avoided the idea that humans can learn something from nature. He has described himself as an atheist and fairly consistently refused to talk about nature as if it has something divine about it. Herzog’s movies generally describe nature as dark, vast, and cruel. In Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams about the making of Fitzcarraldo, Herzog is interviewed describing the Peruvian jungle as a dark place that God left unfinished, a vast “web of death.” In his (perhaps tongue-in-cheek) 1999 speech, the Minnesota Declaration, Herzog stated, “Mother Nature doesn’t call, doesn’t speak to you,” and that “We ought to be grateful that the Universe out there knows no smile.” Characters like Aguirre are fools because they think they can master or overcome natural forces. This is a long way from contemporary Terrence Malick’s vision of nature in World War II drama The Thin Red Line, where nature is a beautiful place imbued with divinity that humans can learn from if they reconnect with the land.

Yet here, Herzog seems to be reaching for divinity. This time around, nature doesn’t eat his character alive. There are some surprisingly tender, metaphysical moments where Onada considers how nature has changed him. After ending his service and retiring in Japan, he becomes a rancher in Brazil and strides in his fields, contemplating the night sky. Onada may not become an unabashed nature lover like Private Witt in The Thin Red Line, but he’s far closer to that character than Aguirre or Fitzcarraldo.

How much Herzog sees this as an evolution from his early work is hard to say. Writers like Andrew O’Hehir have suggested that recent movies like the 2011 documentary Into the Abyss show Herzog balancing respect for Christianity with maintaining his atheism. Heroz doesn’t appear (or at least hasn’t admitted) to become more spiritual as he’s aged. Every Man for Himself and God Against All admits he had a religious phase in his twenties but ascribes that religious longing to misplaced romantic longing for women. The autobiography ends with Herzog pondering a future where our languages will be forgotten, and knowledge of our lives will become inaccessible to future generations. Yet in Twilight of the Worlds, Herzog’s protagonist finds something redemptive, poetic, divine in nature. Do his characters capture his feelings better than his public statements? Hard to say. Time will tell.

Scholars will probably argue for some time about how The Twilight World compares to more famous man-versus-nature novels (Heart of Darkness, Robinson Crusoe, etc.). Whether it becomes a new classic in the canon, it is certainly compelling and worth exploring.

Publication Information (English Edition)

Title: The Twilight World

Author: Werner Herzog, translated by Michael Hoffman

Publisher: Penguin Press

Publication Date: June 14, 2022

ISBN: 9780593490266