BY G. CONNOR SALTER

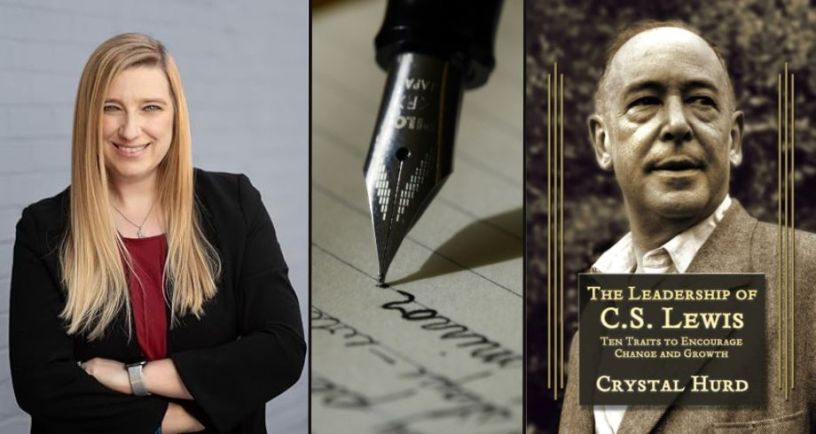

Dr. Crystal Hurd earned her doctorate with a thesis on “Transformational Leadership in the Life and Works of C.S. Lewis.” Along with turning that dissertation into a book (The Leadership of C.S. Lewis) she has also written the devotional Thirty Days with C.S. Lewis and contributed to the collection Women and C.S. Lewis. She is currently the Review Editor for Sehnsucht, where she has contributed book reviews and published never-before-released work from C.S. Lewis archives. She has also delivered talks on the Inklings for Northwind Theological Seminary, and given interviews for the C.S. Lewis Foundation, Pints with Jack, Leading Saints, Men With Chests, the Wade Center Podcast, and All About Jack.

Currently, she is writing a book on Lewis’ paternal and maternal families—the Lewises and the Hamiltons. She is particularly looking forward to sharing details about his father, solicitor (and occasional fiction writer) Albert J. Lewis.

She was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

When did you become exposed to C.S. Lewis’ work?

I remember someone mentioning him to me in 2002, right after I graduated from the University of Tennessee. I was lamenting how there aren’t any good Christian writers who really challenged my mind and faith (like classic authors do). A friend of mine casually mentioned Mere Christianity, so I picked it up at the bookstore the next time I went. To say it changed my life (as cliché as that sounds) is really an understatement. That book changed the way I think about life, my faith, and my purpose. After that, I went “through the wardrobe” to other Lewis works.

When did you transition from being a fan of the Inklings to writing about them?

My dissertation was the perfect excuse to start writing about them! Around the time I was finishing my doctorate, I started a blog, which focused on my research and other related topics to Lewis. It was really an extension of what I was doing for grad school. However, I kept seeing all of these fascinating aspects of Lewis’s life and work, and I wanted an outlet to share those observations. Then I began doing conferences. The first one I attended was Taylor University’s C.S. Lewis and Friends Colloquium in 2012. I met lifelong friends there, and it showed me that there are many opportunities to read, research, and reflect on the Inklings.

You picked a unique topic for your dissertation. Most people writing a thesis on Lewis would do something on literary symbolism or his biography, but you focused on seeing him as a leader. How did you become interested in that angle?

My doctorate is in Education Leadership and Policy Analysis, so I noticed how Lewis fit the expectations of a Transformational Leader. There was almost no research on how artists serve as leaders. Yet, when we think about it, writers have unparalleled access to our minds. They shape our thoughts and imaginations in new and innovative ways. To me, it was not a giant leap to interpreting him as a leader. He wouldn’t have considered himself one, yet he possessed all of the characteristics. Leadership theory has progressed significantly in the last hundred years. During Lewis’s lifetime, the “Great Man Theory” was prominent. This theory argued that tall men with a booming voice and instant charisma often made the best leaders. While many leaders had these qualities, they weren’t the only signs of effective leadership. Lewis once described himself as “short and fat” to one of his child correspondents. He didn’t feel that he had those required traits, but he fought valiantly in battle and knew how to bring dissenting voices to the table to discuss issues during his tenure as the president of the Socratic Club.

You’ve co-written an article with Charlie W. Starr on the Lanier Theological Library’s archives of C.S. Lewis’ work. How much of your work do you estimate involves exploring archives?

All of it. Honestly, looking through the archives is the best part. It’s like treasure hunting!

What are some key pieces of advice you would give first-time researchers about using archives’ resources well?

I would definitely suggest committing to research. Google your topic and see what is out there. If scholarship already exists, build on that. Email the writer/researcher. Ask questions. Be curious and humble. Find a mentor.

You pointed out in a 2015 article for VII that Albert Lewis is “often characterized as a negligent, self-consumed patriarch, whose absenteeism and unfailing obedience to routine were misconstrued as a lack of love by his sons.” How did you become interested in exploring the truth behind this mischaracterization?

This is a funny story! In 2013, my husband and I won tickets to a NASCAR race in Wisconsin, so we planned a day at the Wade Center. I did some preliminary research on the leadership aspect, then I decided to peruse the stacks. One of the archivists suggested that I look through the Lewis Papers, which is an unpublished 11-volume collection of family correspondence and paper excerpts.

As I began to read through it, I noticed that Albert was actually warm, humorous, and encouraging in his day-to-day writing. I had a moment of cognitive dissonance thinking, this isn’t how he is portrayed in all the biographies. Diving into the Papers further, I found an exchange with Warren in which Albert tells him that his selection of underwear is “old-manish.” I laughed out loud in the Reading Room at the Wade! At that point, I decided that Albert needed a defense himself. He has been mischaracterized by so many biographers, yet the correspondence revealed that he tried to connect with his sons through literature and humor.

Forgive me if I’m mistaken, but didn’t Albert lose another relative the year his wife, Flora, died?

Yes, two actually. He lost his father and his brother all during 1908. That was an incredibly tough year for him.

What are some key things that people overlook about Albert?

Most people don’t know that Albert grew up in the working class. His father was a boilermaker, and most of his brothers ended up working in boilermaking and ropemaking. Albert is a bit of an anomaly. He actually went to Lurgan College for a brief time before his father could no longer afford for him to attend. At that time, he apprenticed as a solicitor to help ease the financial burden on his parents. Perhaps this is why Albert was so patient (and generous) with C.S. Lewis as he endured his three Firsts at Oxford. Albert, as a police court solicitor, defended many people who were disenfranchised and could not afford representation. He was exceptionally good at his job.

In 2020, you published something unexpected in Sehnsuccht: a short story written by Albert. How did you discover this story?

“The Story of the Half Sovereign” was a joy to discover when I found it buried in The Lewis Papers. Just for reference, it follows the story of a poor man who tries to buy some food for Christmas dinner, but he is accused of passing a fake coin to pay for the food. He ends up in jail for many months while his family suffers. He is later found innocent, but the story illustrates how prejudiced the aristocracy is against those who are poor and destitute.

How would you describe Albert’s writing style?

Much like his son. Albert’s fictional prose reads a lot like Charles Dickens or Anthony Trollope. His speeches are incredibly similar to C.S. Lewis’s style: lots of allusions to the Bible and literature, arguments which appeal to logic as much as passion. His speeches are teeming with historical references. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree!

You’ve also written about other underdiscussed members of the Lewis family, such as his aunt Lillian. Who are some other underdiscussed people in Inklings studies that you’d like to see more research on?

It excites me to see scholars like Sarah Waters, who is doing some amazing research on Lewis and Shakespeare. Also, Sarah O’Dell’s work on Dr. Havard is incredibly exciting. I would love to see a wider embrace of George MacDonald’s work and more enthusiasm on the writings of Charles Williams (Sørina Higgins has done great work). Women associated with the Inklings, such as Dorothy Sayers and Joy Davidman, would also illustrate some broader contributions. Secretly, I want to see some work on Austin Farrer’s wife, Katherine. She was a crime writer.

You contributed a wonderful piece to Sehnsucht in 2016 after Bruce L. Edward’s passing, mentioning how he encouraged you early in your academic career. How important are mentors and community to good scholarship?

I cannot articulate how important it is to have a mentor. Bruce was not only a dear friend, but a guide when I was just striking out into the scholarship community. His wisdom and advice continue to encourage me to this day. I still have his emails. Mentors know the territory, and they can help new folks navigate the landscape. I remember asking Bruce about aspects on Lewis, on publishing, on submitting articles. He dispelled so many myths for me but also he took time out of his busy schedule to give words of praise and reassurance.

What are some ways that you’ve benefitted and grown from the Inklings scholarship community?

The Inklings Scholarship community has helped me realize that heart and head are not diametrically opposed. We can have the brilliant glow of the imagination married to the pragmatics of the intellect, and they can improve one another. They are allies, not adversaries. God designed us with this cooperation of qualities in mind. All of us are on this journey together, so it is important to share a conversation (and a cuppa) with fellow pilgrims.

More information about Hurd’s work can be found on her website and Amazon page.