BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Dr. Don W. King (PhD, University of North Carolina at Greensboro) teaches British literature at Montreat College. He has published a wide variety of work, particularly in Christian Scholar’s Review (which he edited from 1999 to 2015), and Christianity & Literature.

Most notably, he has published a variety of works on the Inklings, published in all four major Inklings journals (Sehnsucht, Mythlore, VII, and the Journal of Inklings Studies) and contributions to the C.S. Lewis Encyclopedia and the multi-volume C.S. Lewis: Life, Works, and Legacy.

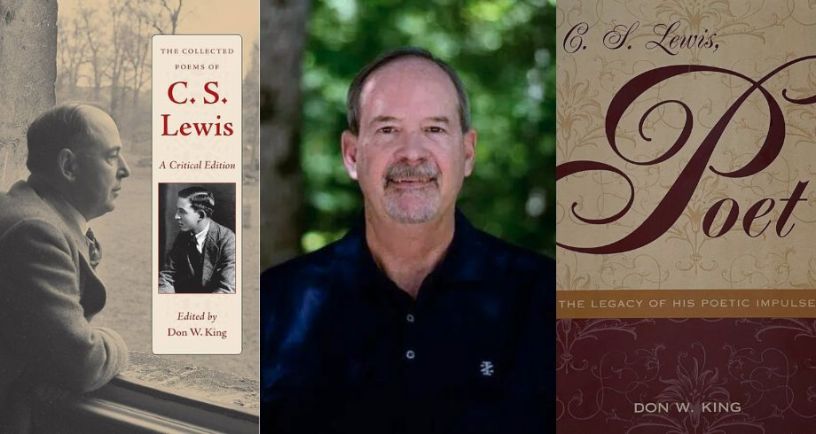

King’s own books have focused on under-discussed areas of Inklings scholarship, such as Lewis’ poetry (C.S. Lewis, Poet: The Legacy of His Poetic Impulse and The Collected Poems of C.S. Lewis), a woman he reportedly considered marrying (Hunting the Unicorn: A Critical Biography of Ruth Pitter) and the woman he did marry (Out of My Bone: The Letters of Joy Davidman, and Yet One More Spring: A Critical Study of the Works of Joy Davidman). His book on Lewis’ older brother, Inkling, Soldier, and Brother: A Life of Warren Hamilton Lewis, won the Bronze Independent Publisher Book of the Year Award in 2023.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions. Because his answers on his major research topics were so informative and detailed, this interview will be divided into several articles. In this first installment, we look at his work on C.S. Lewis’ poetry and his reflections on Inklings scholarship.

Interview Questions

If I’m reading your list of publications correctly, your first academic publication on the Inklings appeared in 1984 in Mythlore, which makes this your fortieth anniversary as an Inklings scholar. How does it feel to reach that landmark?

First of all, thanks to you, Connor, for this interview. I’m always happy to talk about Lewis and those around him.

Now to your questions. Forty years ago, I never would’ve imagined that I would’ve written so much on the Inklings and in particular on C. S. Lewis, but as time has gone by, I’ve simply followed like many other scholars a passion that came to me unexpectedly. I’m so happy to have done what I’ve done and very thankful for all the help that I’ve gotten along the way.

Not many people discuss Lewis as a poet. How did you become interested in that side of his work?

I first became interested in Lewis as a poet in the mid-1980s. At the time I thought I had read everything that Lewis had written, but then I came across his Spirits and Bondage (1919) and Dymer (1926); to me it was telling that his first two published works were volumes of poetry. Then I read Poems (1964) and Narrative Poems (1969), that Walter Hooper had edited and published. I thought, wow this is intriguing, so I started reading his poetry in earnest and became fascinated with his incredible desire as a young man to become a great poet. Indeed, up until his mid to late 20s Lewis yearned to achieve acclaim as a great poet.

I tried to find what kind of scholarship there was available on Lewis as a poet, but almost nothing had been published on him as a poet. So from the mid-80s to the late 90s I was on a path of trying to find, read, and study all of his poetry. Eventually in 2001 I published my book on as a poet: C.S. Lewis Poet: The Legacy of His Poetic Impulse.

By the way, I make two main contentions about Lewis as a poet. First, although he is not a great poet—like a Yeats, Eliot, or Heaney—he is a very good poet. People sometimes too quickly dismiss Lewis as a poet, and I think that is a huge mistake. Why? Because of my second contention: that some of Lewis’s best poetry appears in his prose. That is, we see in his poetic prose (defined as “ordinary spoken and written language (prose) that makes use of cadence, rhythm, figurative language, or other devices ordinarily associated with poetry” Harry Shaw) the longing lasting influence of that early desire to be a great poet. Poetic prose flows often from Lewis’s pen. For example, think about chapter 3, 4, and 17 in Perelandra, multiple passages in the Narnia series, and all of A Grief Observed.

Forgive me if this is incorrect, but it seems like Lewis becomes disillusioned about being a poet after his early books (Spirits in Bondage, Dymer) don’t have the success he hoped. Do you see that affecting his poetry—his themes changing, his style changing, anything like that?

During his years of trying to become a great poet, Lewis modeled his verse upon older, traditional poetic forms, especially long, narrative poems and retellings of old myths, characterized by frequent archaisms and the use of traditional meters. Among the poetic works influencing him the most were Homer’s Iliad; Thomas Malory’s Morte D’Arthur; Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queen; the anonymously written Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; John Milton’s “Comus” and Paradise Lost; Percy Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound; William Wordsworth’s The Prelude; and William Morris’s Sigurd the Volsung.

When Lewis “died” to the idea of being a great poet after the tepid critical reception of Spirits in Bondage and Dymer, his gift in prose was released. Although he continued to write and publish poetry (often under the pseudonym “N. W.” Anglo-Saxon shorthand for “I know not whom”), it was no longer with the desire to become a great poet. It is no exaggeration to say that when God killed Lewis’s desire to be a great poet, He also released in Lewis an imaginative fountain head that no one—including Lewis—could have ever imagined.

You’ve done some great research into understudied Inklings figures and topics. What’s some advice you would give to anyone trying to explore an understudied Inklings topic?

All my research and writing has been driven essentially by one thing: coming across something I was really interested in and that no one else had written about. So in a sense all my books have as their primary audience me. Of course I’m delighted when others find what I have done interesting or helpful—I don’t write in a complete vacuum. As far as advice goes, I’d say look for aspects of the Inkling that you find compelling and yet under researched or written about. Throw your passion and energy into that topic and write to satisfy your curiosity and interest. Almost certainly others will be interested.

Any future projects you can tell us about?

Yes. Here’s a list:

——–. “Joy Davidman’s Unpublished Letters: January 4, 1949, to December 19, 1952.” VII, Journal of the Marion E. Wade Center 40 (2024): forthcoming.

——–. “Frankenstein’s Nursery Rhymes: The Unpublished Poetry of Joy Davidman.” Sehnsucht: The C. S. Journal 19 (2025). Forthcoming.

——–“C. S. Lewis’s Poetry: Yearning for Lost Eden.” In the Routledge Companion to C. S. Lewis. Eds. Mary Baggett and David Baggett. 2025. Forthcoming.

——–. “Review of The Major and the Missionary: The Letters of Warren Hamilton Lewis and Blanche Biggs. By Diana Pavlac Glyer. Journal of Inklings Studies (2025). Forthcoming.

——–. “Amor Agonistes: The Love Sonnets of Louise Labé and Joy Davidman.”

Many of King’s essays on Lewis have been collected in Plain to the Inward Eye: Selected Essays on C.S. Lewis. More information about his work and courses can be found at Montreat College’s website.

Come back next week when King discusses his groundbreaking work on C.S. Lewis’ brother, Warren “Warnie” Hamilton Lewis.