BY G. CONNOR SALTER

According to Nick Tosches, from the moment that William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley was published in 1946, it was “an acclaimed and successful novel, and a damned and banned one.” A dark story about carnival employee Stanton Carlisle’s rise and fall as he uses mentalist tricks to pose as a genuine psychic, it’s considered a key book in post-World War II hardboiled fiction (or, for writers like Paul Duncan, the shift when hardboiled becomes noir).

However, there was a long period when few knew the book outside of carnival and magician aficionado circles (Gresham also wrote a biography of Harry Houdini). Playwright and composer Jonathan Brielle recalls, “In the early 90s, nobody was thinking about Nightmare Alley—except for magicians, except for people who connected to the kinds of worlds that Gresham wrote about. Those kinds of folks really held the book in incredibly high esteem, but outside of that world, it was really not known.”

For Brielle, adapting Nightmare Alley into a musical was a long and curious process. He first heard about the novel in a way that he admits sounds like a joke: “I was working in Los Vegas, and I was sitting at a bar with a ventriloquist.”

The ventriloquist was Jay Johnson, known for his work on the TV show Soap and Broadway shows like Jay Johnson: The Two and Only. “Jay proceeded to tell me the story of Nightmare Alley, and I immediately thought, ‘This is a musical.’”

Later, in New York, Brielle tracked down information about the novel through the public library, the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building on 42nd Street. What he found told him how to explore adaptation rights, but also started his larger search to learn more about the man who wrote Nightmare Alley.

The more Brielle studied Gresham’s life—a man who explored I Ching, Christianity, tarot, and Dianetics, who served as an Abraham Lincoln Brigade medic in the Spanish Civil War, who wrote everything from freelance journalism to science fiction stories—the more he appreciated the writer. “I suspect he was incredibly perceptive about people,” Brielle said. “When you study everything from Freud to tarot to religions, you gain a certain wisdom and knowledge about people.”

Brielle also found that he resonated with Gresham’s search for meaning. “I had sort of my own studies with the occult and with psychics and with tarot as well as Freud. I had similar callings.”

He could also relate to how Gresham pursued many pathways to deal with inner pain. “I had my own journey with depression. Believe me, I did not suffer the way Mr. Gresham suffered being in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and I can’t even imagine what that horrific experience was like. But I also went to analysis for 19 years—strict Freudian analysis. I studied many different religions, I was a searcher as well in my younger years. So, I really related to Mr. Gresham and the journey he was on, his dealing with alcohol.”

While Brielle knew he wanted to make a musical from Nightmare Alley, he had to establish the rights first. Ironically, a lawsuit involving another noir writer, Cornell Woolrich, had recently changed the process. Woolrich’s 1942 short story “It Had to Be Murder” was adapted into the Alfred Hitchcock classic Rear Window, starring and co-produced by Jimmy Steward. Woolrich died in 1968, and his executor renewed the story’s copyright in 1969 before selling the rights to literary agent Sheldon Abend. Abend sued Stewart in 1971 and 1988 over Rear Window being aired on TV and later re-released in theaters and on video without Abend’s permission. The Supreme Court ruled in Abend’s favor in 1990, establishing a new precedent.

“If a writer doesn’t survive the copyright renewal, it reverts back to their estate,” Jonathan explains, “so the rights went to his widow, Mrs. Gresham.”

Let’s Make Some Magic: Getting Permission for Nightmare Alley

As many people familiar with Gresham’s life story know, he had two sons, David and Douglas, with writer Joy Davidman. They separated in 1953, and Davidman moved with their sons to England. She later married C.S. Lewis (a story that became the basis for a play and multiple movies called Shadowlands). After their 1954 divorce, Gresham married Davidman’s cousin, Renée Rodriguez, and they stayed married until his death.

In 1992, Brielle met Renée, who lived in Ocala, Florida. “I arrived at around 9 am and left at 10 pm, we literally spent the day together,” he recalled. “She invited me in immediately and said, ‘Have you ever seen the movie?’ I said no, and she said, ‘Would you like to see it?’”

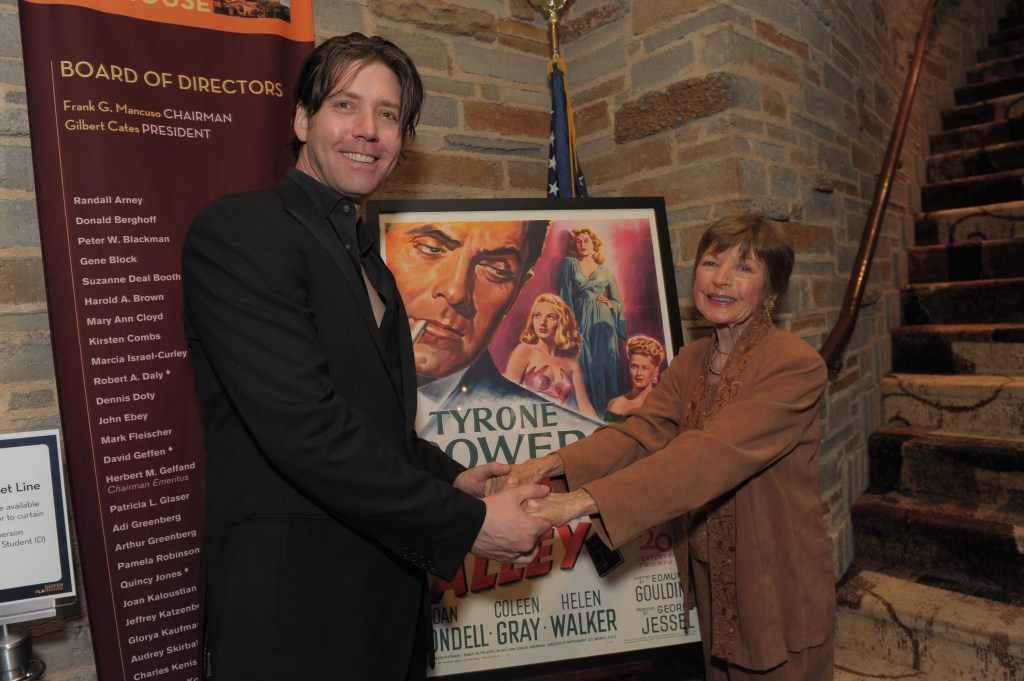

The movie, released in 1947, starring Tyrone Power and directed by Edmund Goulding, was famously one of the higher-budget film noirs. Gresham spent some time in California while the movie was being shot, although it’s unclear whether he contributed to its script.

Brielle and Renée watched the movie in the ranch house’s living room. A large painting of Gresham by Richard Schmid hung on one wall under a large chair. Renée mentioned it was Bill’s chair and directed Brielle to sit in it.

They watched the movie from a videotape of a TV broadcast—one of the few ways to see the movie. Kim Morgan writes that a lawsuit between Fox and the estate of producer George Jessell kept the movie from being shown on TV or home media for some time. The movie wasn’t available on home media until 2005.

After the movie, Renée asked if he’d like a tarot card reading from Bill’s cards.

“I was sitting on the edge of their bed, and I believe the tarot card was wrapped in a silk scarf, as tarot cards are, generally,” Brielle recalled. He cut the deck and pulled the magician card. “I thought that was a lovely sign.”

They talked about Gresham, the book, and the movie for the rest of the day. “We just had a grand old time,” Brielle recalled. “Clearly, she still very much loved him.”

Much of their conversation involved the ending. The novel ends with a disheartened Stan on the run seeking work at a carnival and being offered a job. “Of course, it’s only temporary,” the carnival boss says. “Until we get a real geek.” In carnival shows, a geek was a performer who pretended to be feral and bit heads off chickens and snakes. Spain Rodriguez’s 2003 graphic novel Nightmare Alley adds a little addendum: Stan walks away, then stops and returns to the carnival boss. The 1947 movie ends with Stan’s wife, Molly, finding him at the new carnival and promising to take care of him.

“We talked about the ending a lot,” Brielle recalled. “Renée said that Bill had felt okay about it and realized that to make a Hollywood film, that was what it needed to be.”

Near the end of the day, Brielle took Renée to dinner. During the meal, she said something unexpected: “She told me that Bill had hung himself because he had tongue cancer.”

As many researchers know, Bill Gresham checked into the Dixie Hotel in New York on September 14, 1962, and was found dead the next day. He had been diagnosed with inoperable tongue cancer—probably, Alan Wald notes, caused by chemicals in lighter fluid Gresham put in his mouth for a fire-eating act at parties.

Bret Wood reports that Gresham’s limited finances did not allow for treatment, and being a former tuberculosis patient disqualified him from life insurance. Renée and her children, Rosemary and Bob, would be left destitute if Gresham tried to fight the cancer, and no money if he died. Gresham also knew firsthand how cancer could affect people: his friend Rufus Bush had died from tongue cancer, and Davidman had died from breast cancer. When his body was found the next day, the coroner’s report stated that Gresham died from overdosing on sleeping pills.

Brielle isn’t sure how to reconcile the report with Renée’s information—whether the coroner wanted to spare the family’s feelings or some other option. More than anything, he was affected by how Renée, after only knowing him for day, trusted him with that detail. It was as if she needed to confess it. “It was such a revealing, heavy moment. It took her all day to tell me.”

Renée also told him he’d need permission from Bill’s sons for a musical. “She spoke very warmly of Douglas, and that he was over in Ireland, and that I would have to be in touch, but that David would probably not be available.”

As many scholars working on Gresham or Davidman had learned, David Gresham was very private. He didn’t leave his home in Switzerland to meet Brielle but permitted the musical. “The only contact I had with David was through the attorneys and signatures on things,” Brielle remembered.

Douglas Gresham, later known for his work with the C.S. Lewis estate, was a little more accessible. Brielle remembers Douglas as supporting the idea as long as it benefitted the right person. “He was very loving and caring about Renée,” Brielle recalled. He was very concerned about making sure that Renée was cared for.”

I Haven’t Any Lines: Writing Nightmare Alley

Once Brielle had the legal support, it was still rough going. “Creating a musical has the gestation of way longer than an elephant. It takes years to launch these things.” It also presented some new artistic challenges for him. “I had had a show on Broadway, but I had never been the book writer—the adaptor—as well as the music writer.”

Brielle had the right to develop the musical on a short-term basis, renewing his option regularly as long as he showed he had produced a certain amount of progress. Around 1995, he revisited Ocala to perform some of the songs for Renée. “She seemed quite pleased and allowed me to keep going and keep working on it.”

One person became very supportive at the time. Selma Luttinger was an assistant with the Robert A. Freedman Literary Agency and had a connection with Gresham’s executor, Brandt & Brandt. Luttinger regularly encouraged Brielle to work on the project and got him copies of Gresham’s other books. “She was lovely,” he recalled. “She was really an advocate for me and a supporter of Bill’s work. She became a fan of mine and a fan of the shows and really supported it. At the same time, she really supported Renée and the family.”

Brielle recalled how Selma balanced those roles well when she told him about an offer to sell the movie rights to an interested movie company. He released that section of the derivative rights, which led to some money for Renée.

Adapting the story meant Brielle had to decide what would and wouldn’t work on stage. Sometimes the changes were pragmatic—for example, changing the name of Ezra Grindle, a wealthy businessman that Stan tries to con. “I found that Grindle is a hard name for an actor to pronounce. So, I changed it to Grimble, because Grimble was just easier on the actors. Grindle is just not as euphonious or something, it doesn’t flow as easily.”

Other changes took more development. “I noticed when adapting that the women were really a bit thin, a bit one-dimensional.” It wasn’t that Gresham didn’t make the female characters memorable. He gave them strong names that implied their character—like a psychoanalyst named Lillith Ritter, named for a demonic figure in Jewish mythology. “Lillith—choosing the name Lillith was like, ‘Here comes, look out…’ Names aren’t chosen randomly. They’re just not.”

Gresham could also give his female characters strong backstories—like Molly’s memories of her con artist father teaching her how to leave a hotel without paying the bill. Yet even there, Brielle noticed he was learning a lot about Molly but not about her emotions. So, the women were memorable but not necessarily well-characterized.

“His women were not as fully painted as the men in the story. You think about how Molly was, it’s borderline trope-y. I think as a southern boy, Gresham had certain ideals at the time he wrote it.” Brielle quipped, “That’s my Freudian take, as someone who did Freudian analysis, on why the women were thin.”

Curtain Time: Staging Nightmare Alley

In 1996, the Director’s Company in New York worked with Primary Stages to do a workshop production of Nightmare Alley. At that point, the second act was well-developed—and coincidentally, explored material rarely appearing in Nightmare Alley adaptations. The 1947 movie shows Stan marrying Molly and going on the road as a nightclub mentalist act, which leads to him meeting Lillith Ritter, who helps him set up an elaborate con job on Grindle. However, in the book, Stan meets Ritter after some time working as a spiritualist minister, using a house with hidden gadgets and Molly’s help to trick wealthy clients with names like Mrs. Peabody.

The 1996 workshop highlighted this spiritualist phase, with Stan declaring himself to be a reverend. “It was very entertaining,” Brielle recalled. “It was slightly tongue-in-cheek and a wink. I had Molly coming out of the cabinet and a magician helping us do all the gags. Mrs. Peabody was there getting conned and also Grindle—they were all there in a big musical number about convincing people by telling them what they already know.”

However, the first act, covering Stan’s time working at a carnival where he learns mentalism and meets Molly, still needed work. Since it was a detailed look at the carnival community—including Stan learning mentalism from fortuneteller Madame Zeena and her husband Pete—there was much ground to cover before getting to the reverend material. “Setting the stage for what happens in the act when he’s conning people—there’s a lot,” Brielle reflected. “I wanted to get it right, and the world of carny right.”

In 2007, he met Gilbert Cates, artistic director of Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles. “Because Gil was so enamored with the world of carnival and circus, even though he was the artistic director, he said, ‘I really want to direct this.’ We became great friends, and he became my mentor and the older brother I never had.”

The musical premiered on April 13, 2010, at Geffen Playhouse. Brielle sadly had to cut the second act he loved so much due to a more famous 2010 musical exploring similar territory. “After the musical Leap of Faith, which was based on the Steve Martin movie, came out, it felt like, ‘Ooh, this is well-worn territory.’ So, I started looking at how to skip that portion of the novel and get right to the convincing of Grindle.”

The reviews for Nightmare Alley were mixed. Brielle suspects the main problem was the show was treated too seriously too soon. “Part of a musical’s journey is that you like to see productions that are developmental productions. In the old days, you would go to Boston, go to Philly, go to Baltimore, and make changes all along the way, and then you get to go to New York. I was thinking, the Geffen Playhouse being in Los Angeles and me being a New York-centric guy, ‘well, this is out-of-town for me.’ Except the Geffen Playhouse is not viewed as out-of-town, and we were reviewed as if we were in-town, and we weren’t finished.”

The Geffen Playhouse production held its last performance on May 23, 2010. While the production wasn’t a rousing success, it helped accomplish a milestone. The number of performances met 75 percent of the performance quota to “merge the rights” so Brielle wouldn’t have to renew his adaptation rights regularly. Brielle met the final quota by taking the musical to New York for 24 performances at a small Greenwich Village theater. He now had the long-term rights for his adaptation secured.

See You Next Season: The Future of Nightmare Alley

Since 2010, Brielle has continued to develop the play. “Until the play’s got its main audience and is published, I’m still tweaking it.”

Establishing long-term rights has allowed him to make smaller versions to experiment with. He has considered making what he calls a muzi, a shortened musical only covering the first chapter. “I’ve been toying with a muzi of Nightmare Alley so that you’d want to binge it, so to speak, so you’d want to see the next chapter.”

He’s shared some of these shorter versions with the public. “I’ve done a 20-minute version as an intro to get people interested in it, which was incredibly successful at New Jersey Rep for two years in a row at a short play festival. They would really like to produce it. I just haven’t been able to do it yet.”

Brielle came close to staging Nightmare Alley in 2016, but with a producer who asked if they could do another project first: A Complicated Woman, based on the life of intersex theatre producer John Kenley. That musical finished its run in June 2024, a month after this interview took place.

Another interesting factor is that Nightmare Alley is no longer known just for the novel or the 1947 movie. Guillermo del Toro eventually acquired the movie rights that Brielle had sold, and released his movie Nightmare Alley in 2021. Seeing the movie has challenged Brielle to consider new ways to handle the material.

Like many movie critics, he found the pacing dragged a bit. “It’s gorgeously shot, but it’s a little slow, and it doesn’t have to be because so much happens.”

Brielle does admire “the incredible performance that Cate Blanchett gave” as Ritter. Since he struggled to make female characters more complex, he admired how del Toro hinted at a dark backstory when Ritter shows Stan a huge scar on her chest. “Guillermo gave her some depth by showing what motivated her. She was suffering from the feeling that she had to be the baddest bear in the woods because of what happened to her. When she shows Stan her scar, she’s saying, ‘This is who I am, this is who I have to be.’ Guillermo gave her some interesting depth that I don’t recall being in the novel.”

At the same time, Brielle balances respecting the movie with affirming he has a different vision. “Guillermo creates beautiful stories, and he’s quite an artist. I just think my angle on the story is a little different. I find it more interesting to have Stan a little closer to Gresham and have Stan as having potential.”

In Tears by the Third Act: Finding an Ending for Nightmare Alley

That difference in perspective affects how Brielle sees the ending. The del Toro film ends more darkly than the novel. After the carnival boss offers Stan a job playing the geek, he asks Stan if he can do it. Stan laughs and replies, “I was born for it.”

Brielle suggests this ending reflects del Toro’s religious upbringing. “What’s interesting about Guillermo’s take is that being Catholic—or raised Catholic, I assume—he has a very right and wrong thing. The first movie was interesting in that they ended the film with, ‘He tried to fly too close to the sun.’ It was a different moral: ‘You can’t reach too high in life.’”

Brielle experimented with a similarly dark ending. In the Geffen Playhouse version, “Stan really goes down the tubes. I didn’t do the Hollywood ending in my first production. It’s a tough role to play because it can really take a toll on you. You have to take that emotional journey.”

Ultimately, Brielle found this ending challenging not only for the actors but also for the form. Relentless tragedy doesn’t work well in musical theatre.

“A musical—even the darkest of musicals, like Sweeney Todd—generally has hope at the end of it,” he explained. “The basic formula of a musical is love overcomes an obstacle, which equals hope. Musicals are a very American art form created by immigrants in the beginning of the 1900s, so it was an outlet to have hope. Even with Sweeney—which is basically a revenge piece, so you go on the ride knowing they kind of all deserve it, and yet our moralistic selves go, ‘Yeah, he can’t live through this’—they very wisely had the next generation sing the last song, which gives you some sense of hope that maybe we’ll get past that revenge feeling.”

More than that, Brielle suspects his feelings about the ending are rooted in how he perceives evil and its consequences. He agrees that Stan is no saint. “What’s so brilliantly written in Gresham’s novel is you’re rooting for this bad guy. It’s such a well-written novel.” Yet while del Toro’s take seems to be “When a bad person does bad things, bad things happen to them,” Brielle sees evil more in terms of people hurting themselves when they do harmful things. “There’s a karmic law that what you put out, you get. You attract like energy.”

If del Toro’s film is ultimately about judgment, it’s perhaps key that the movie opens with a scene implying that Stan has a criminal secret. He is a likable but damned figure from the start, therefore born to play the geek. Brielle prefers to see hope for eventual redemption. “For me, I couldn’t make a musical about a guy who does bad things and just keeps doing bad, keeps doing bad, keeps doing bad. I believe that we all start out as innocents somewhere.”

Since Brielle wants to see hope and progress in the story, he wonders how to create a “save the cat” moment—something that makes audiences sympathize with Stan, even if he’s flawed. He compares the dilemma to Frank Underwood’s first scene in House of Cards, where Underwood breaks a puppy’s neck after a car has hit the puppy. “All in one, it’s an act of ruthlessness and kindness.” The struggle for Nightmare Alley becomes how to make that kind of scene possible after the hero has been very ruthless. “Even if you’ve burned a lot of bridges behind you, which Stan Carlisle does, is there any way to make it back?”

Stan is the Author: Redemption in Nightmare Alley

For Brielle, the solution partly involves the fact that, like many researchers, he sees Stan as similar to Gresham. Several times in the interview, he talks about them almost interchangeably. When he discusses Gresham’s insights into people, he says, “I think that Gresham—as well as Stan—were incredibly perceptive about people.” Referencing the novel’s scene where Stan draws the hanged man card from Zeena’s tarot deck, Brielle comments, “What fascinated me was that Gresham was the hanged man. He wasn’t dead. He was suspended. To me, that gives us the option that there’s hope. They’re going to be changed, and they’re not going to be who they were. But I think hope is essential in the world.”

According to Tosches, there is a note in the Marion E. Wade Center’s archives where Gresham wrote, “Stan is the author” of Nightmare Alley.

If Stan is comparable to Gresham, that leads back to the 1947 movie. Like Stan, Gresham hit a low point. His divorce from Davidman meant the end of a marriage, of a writing collaboration, and separation from his sons. But all accounts agree that he became sober and happily married to Renée.

“I think Renée was an incredible influence, as anyone’s partner in life can be, and somehow he was able to maintain his sobriety,” Brielle said. “Clearly, her love helped him.”

Given Gresham’s death, it wasn’t a love story with the happiest of endings. “He chose not to fight cancer, and he chose to end his life—that was either a decision done out of fear or out of love for Renée and not wanting to put her through that. Only the gods know the answer to that.”

For all the sadness, Brielle still sees Gresham’s life as essentially hopeful. The fact that Gresham accepted the 1947 movie ending, where Molly finds the degraded Stan and he gets a chance to move on despite having scars, permits Brielle to provide a redemptive note in the musical.

“I believe that Gresham’s acceptance of what Hollywood did to the end of the story, according to Renée, meant that he believed love could heal. It doesn’t make up for, doesn’t forgive, all the horrific things that Stan the character did—and maybe in Gresham’s own eyes, his own judgment of his own failings. But his love, and feeling loved by Renée, healed him in some way.”

It’s clear that for Brielle, hope for healing is something we can all aspire to—even when talking about the kind of dark, fatalistic events that noir fiction explores. “We all have, in our lives, our karmic tie to those who came before us. We either repeat what our parents have done, what their parents did, or we break the karmic tie. Breaking the karmic tie is an opportunity to move forward. I believe that humanity tends to take three steps forward and two steps back. But my optimistic self, because I do write musicals and I do believe in hope, says that’s one step we’ve gained.”

Jonathan Brielle is currently developing his next production of Nightmare Alley, with updates eventually available on his website. Music from Nightmare Alley is available on his SoundCloud profile.

(Article first published on July 18, 2024).