BY G. CONNOR SALTER

In a previous article, Jonathan Brielle shared his journey adapting Nightmare Alley from the original novel. The following contains his reflections on Freudian analysis, the tarot, and other subjects that couldn’t be included in that article for space reasons.

Making a musical is always complicated.

You have the physical factors based on where the musical is staged. “You have limitations of how and where you’re going to produce it,” Brielle explains, “and those limitations are sometimes incredible opportunities to be creative and create a visual vocabulary with the show.”

Then there are people you work with. “When you’re starting with a new piece of theatre, you’re trying to create the ultimate version that will stand the test of time. Within that, you marry a director, and as in any marriage, you have a give and take.”

However, another important factor is understanding the subject matter—in this case, William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel Nightmare Alley. “All of the shows that I’ve done have been very involved in some way with the creators of the show,” Brielle says. “What I mean by that is that it was just as important to me to feel and see Gresham’s intention, maybe things that he hadn’t figured out for himself. Psychologically, why was he so attracted to ‘how does a man ever get that low?’ You wonder that because there’s a part of you that goes, ‘Well, but for the grace of God, there go I.’”

The story in Nightmare Alley is undoubtedly dark: it begins with Stanton Carlisle seeing a geek show—a man playing at being feral in a cage and eating live chickens or snakes. It follows Stan’s attempts to achieve fame and fortune by posing as a psychic. It ends cycling back to something similar to the first scene. It’s also a deeply personal book, informed by Gresham’s struggles with alcoholism, fascination with psychics and carnivals, not to mention his time receiving psychoanalysis after serving in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War.

Brielle found he could appreciate many parts of Gresham’s journey, particularly his search for enlightenment in different worldviews, from tarot to I Ching to Dianetics. “I’ve experimented in my life, in my twenties. I read Carlos Castaneda and tried to find my guide, and did all of that in search of what I thought was in search of a truth, when in fact it was dealing with my own form of depression. Life is a funny, tricky thing. There’s no fairness. To me, it’s just about finding joy and leaving the best you can behind. That’s what it’s become for me.”

The Freudian connection was one area in which Brielle particularly resonated with Gresham. Brielle went through 19 years of analysis. “It was incredibly helpful,” Brielle reflected. “I probably went another 12 years too long, and it became an addiction for me.” Gresham’s six years of analysis after Spain inform some crucial scenes in Nightmare Alley where Stan receives therapy from Lillith Ritter, an analyst who helps him exorcise his past but then manipulates him into helping her con a wealthy businessman.

Given Brielle’s understanding that even therapy can become addictive, he appreciated Gresham showing how analysis can go wrong with the wrong motives. “It was a very smart take on what analysis can do. It’s just as easy to manipulate someone through the logic of Freud as it is through tarot. There’s a sense of relief when a person helps you say out loud something that you might have been burying. Imagine that you’re the person that experiences doing it, getting at something… and you feel better.”

Brielle gave the example of talking with his analyst about his fear of flying. One day, when he was discussing a particularly terrible flight that had gone through a hurricane, the analyst broke his usual routine. Instead of talking Brielle through an idea so Brielle told it to himself, the analyst gave some direct advice:

“He said that I believed the pilot was my father and, ‘since every son has murderous feelings about your father, you want to murder the pilot, but that meant if you did that, you would die too.’ I walked out of there and wasn’t afraid of flying. Now, it could have been Dumbo’s feather. But my being accepted it. When someone is able to change your emotional state, they have a lot of power over you. If you allow them to have that power, you create a belief system.”

Brielle sees that mix—the relief at getting help, the awareness that there may have been manipulation or wishful thinking involved—as something Gresham captures so well in Ritter’s analysis scenes with Stan. “Gresham knew exactly how to write it and must have had very mixed feelings about whoever his therapist or analyst was, and felt manipulated and yet, at the same time, felt healed. And he connected it to church and contacting your loved ones after death—because you have an opportunity to heal, and that’s so powerful. That’s what’s so fascinating about the novel.”

These ideas suggest a tension. On the one hand, the inner journey may become purely about getting over our neuroses. As Brielle puts it, “Sometimes our searching—whether it’s through religions or other forms—sometimes we’re trying to self-medicate our own conflicts, also sometimes known as depressions.”

On the other hand, Brielle doesn’t disregard these searches as all being con games to make us feel better—what Gresham’s characters would call “a spookshow.” “I think tarot can be an incredible window to the soul,” Brielle says. “I think Freud can be an incredible window to the soul. I think religion, depending on what it is, can be an incredible window to the soul. Or it can be an incredible manipulator if you have ulterior motives and are trying to be the baddest bear in the woods.”

Given that Nightmare Alley shows Stan embracing the temptation to manipulate others, he may be a shrewd man using his knowledge poorly.

“I think that Stan is incredibly perceptive,” Brielle says. “You take that talent and that wisdom and knowledge that you’ve gained over years, and you decide, ‘You know what? The world ain’t handing me any piece of cake today, so I’m going to cut a slice for myself.’”

Taken far enough, of course, the belief we must manipulate to survive makes us feral—as Brielle puts it several times in the interview, we succumb to tropey evil. “You look at the tropey evil in the world today. People who feel you have to be the baddest bear in the woods. Otherwise, you’ll be eaten by another bear.”

Perhaps it leads to becoming feral in another way. Like the geek in Nightmare Alley, whose life choices reduce him to feral circumstances.

All these points about faith, manipulation, and survival raise the question of how we can avoid becoming the manipulators or the manipulated. Perhaps the answer lies in making the systems about more than self-medicating. Brielle sees joy as very important.

“For me, the Achilles heel of analysis is that it focuses on what’s wrong. It focuses on problems. Which is important, but for me, with my analyst, it never focused on joy. I’ve come to the conclusion in life that you don’t ever rid yourself of pain. What we as humans are capable of doing is surrounding ourselves with joy. In a sense, you crowd it out. It’s never gone. It’s true with grief. When someone you love dearly passes, that pain never goes away, but you can surround it with the joy of your life. It’s never gone, but you surround it.”

These reflections have informed not only Brielle portrays analysis in his musical but also how it features the tarot card deck. Fans of the novel will know that not only does the story feature Stan getting a tarot reading from fortuneteller Madame Zeena, but it makes them part of the novel’s structure.

“Since each chapter was headed with a tarot card, I felt the tarot played a really important role in the storytelling,” he explains.

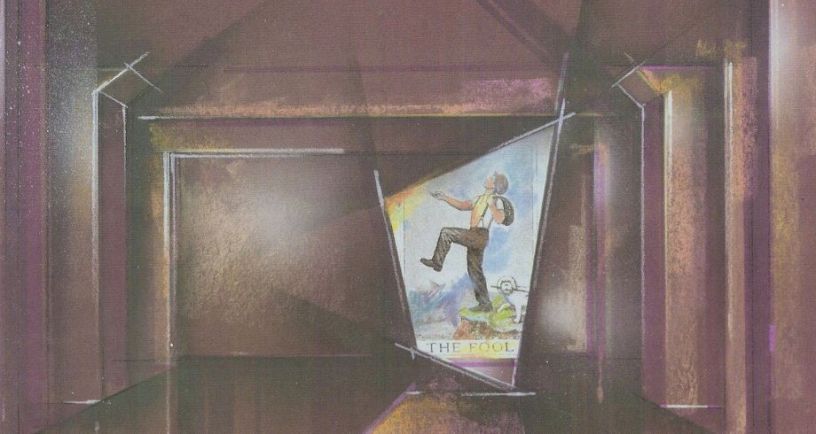

In a 1996 workshop production, he emulated how the first chapter uses the Fool card as its header. “There was a lightbox, and we started the show with the Fool coming out of that card,” he recalled. “In my Geffen production, I was experimenting with Zeena as the storyteller, and the story comes out of the tarot cards.” Fourteen years after the Geffen Playhouse production, he likes to think about more radical ways to feature tarot cards in the play. “There’s a part of me that wants to take the tarot deck and go into different stories for each character.”

The last option, of course, communicates how stories can change. How can we achieve a better outcome, even though we may still feel the effects of our past mistakes?

“We carry our scars,” Brielle reflects. “We can heal ourselves, but not all the scars go away. Love is healing, but it’s like if you’ve amputated an arm, you’re not growing to grow an arm back. There are some things you can’t quite ever get back, but you can move on, and if there’s any meaning to our existence… to me, musicals represent the hope that there is meaning.”

The tarot’s usage in Gresham’s novel has helped Brielle consider how there may be redemption for Stan, as there was for Gresham when he married Renée Rodriguez. Brielle’s meeting with Renée in 1992 to discuss the musical gave him a strong sense that the couple had loved each other very much, and Renée’s love had helped Gresham achieve sobriety. He connects Gresham’s journey from innocence to trauma to healing with the tarot card over the book’s first chapter.

“The book opens with the Fool card,” Brielle says. “What is the Fool? The Fool isn’t an idiot. The Fool is an innocent. The innocent with a foot up in the air, not understanding, with his head in the clouds, and not knowing where he’s going to step down. I think Gresham was the Fool. He was the innocent with his foot in the air and went through some horrible experiences being part of the Lincoln Brigade, and all of that affected him darkly, and left psychological scars. Scars that we are all susceptible to. To me, that’s what makes the story so compelling—and love can save you. It’s not going to remove scars. And whether you’ve done irreparable damage, it’s not going to fix irreparable damage, but it can at least heal you going forward. I still feel a responsibility—I don’t know why. Maybe I feel a responsibility to Renée and her love for Bill, that there is some form of redemption. What it will be, I haven’t figured out. There will be some form.”

To Brielle, that possibility of hope—that the Fool is an innocent who will be broken but can heal, that love can help us along the way—is what the tarot ultimately says in Nightmare Alley.

“What Gresham has laid out, with those 22 chapters and the major arcana, is a journey from innocence to how you can be corrupted. But if you shuffle the deck again, you might get a second chance. I think that’s what the musical’s about.”

Jonathan Brielle is currently developing his next production of Nightmare Alley. Updates will be available on his website. Music from Nightmare Alley is available on his SoundCloud profile.

(Article first published on July 25, 2024).