BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Today, April 9, marks 79 years since Dietrich Bonhoeffer died by execution for resisting the Nazis.

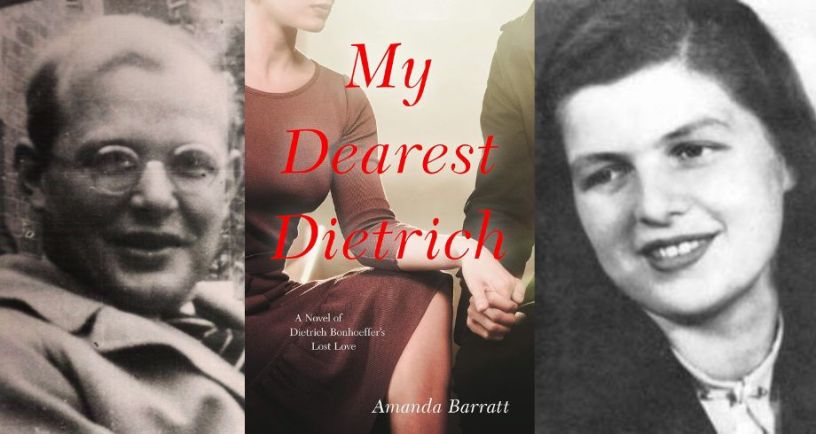

My Dearest Dietrich: A Novel of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Lost Love. By Amanda Barr. Kregel Publications, 2019. ISBN 978-0-8254-4605-4. Historical Romance.

It’s June 1942, and Maria von Wedemeyer has met an unusual man: pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Maria knows little about Dietrich. Only that her grandmother praises his theology books, that Dietrich has preached against the Nazis and taught at an underground seminary. Now, the Gestapo has banned Dietrich from preaching and he’s working for the German military intelligence division. Maria suspects that, like many of her relatives, Dietrich uses his position to fight the Nazis. Dietrich feels that at thirty-six, he’s past romance. Neither expect it when they learn their attraction is mutual.

They know their romance has obstacles. Maria is only eighteen, and Dietrich’s secret work is more dangerous than anyone knows. Despite their attempts to fight it, the connection grows. When Dietrich becomes involved in a plot targeting Hitler, he and Maria must decide what to do about their love.

Much has been written about Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s life—his connection to a Hitler assassination plot, his ethical dilemmas as a pastor who lied to authorities, his martyrdom just before World War II ended. Less has been written about his romance with Maria von Wedemeyer—possibly because, like the love story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Davidman, it’s an unconventional May-December romance. Bonhoeffer wasn’t quite middle-aged, but at thirty-six, he was exactly twice von Wedemeyer’s age. How do we understand a man like Bonhoeffer getting engaged to a woman literally half his age without seeking creepy Freudian explanations?

The problem is not an easy one, and other Bonhoeffer projects have stumbled over this point. For example, a key flaw in the (very flawed) 2000 biopic Bonhoeffer: Agent of Grace is it never makes von Wedemeyer into a nuanced character. She appears a lovesick blonde swooning for a middle-aged man because the plot demands it. Several characters comment on the romance not making sense. One of Bonhoeffer’s guards asks, “Tell me, what does a girl like that see in you?” and he replies “Honestly, Herr Knobloch, I’ve been asking myself the same question.” There’s an element of truth to this point. However, good writing can frame a dilemma (why this relationship was strange but made emotional sense to the couple) so it feels plausible if surprising.

Barr solves this problem by highlighting Maria’s (emotional and intellectual) qualities. She depicts the cleverness and math skills that aided von Wedemeyer when she became a computer scientist in America during the 1950s. Like the depiction of Joy Davidman in Shadowlands, this characterization shows how this woman had the brains and personality to complement (and challenge) the man she fell in love with.

Barr also gives the romance context by quoting the couple’s love letters, and providing dates so readers can track how it progressed as World War II progressed. The letters, plus scenes based on real conversations, show how cautious Dietrich and Maria were about a romance that neither planned. The dates show how events (losing relatives, Gestapo threats) put Maria and Dietrich’s romance in a pressure cooker: they fell in love fast in dark times, and the dark times pushed them closer together.

Along with using facts and quotes for context, Barr depicts the secondary characters in ways that flesh out this surprising romance. She shows Maria’s grandmother (who supported the romance) and her mother (who initially opposed it) as complex individuals. Individuals who sometimes created complications but were clearly real people with understandable motivations. Barr also depicts Bonhoeffer’s 17-year-old niece Renate and her older fiancée Eberhard Bethge, a romance that predated Dietrich and Maria. Seeing how the surprising Bethge romance developed (Dietrich realizing his niece loves his best friend, maybe jealous of his best friend) helps readers see that Dietrich and Maria weren’t the only couple thrown together quickly by World War II.

There are moments where the book feels creaky. Barr occasionally adds fictional characters who feel like stock historical romance characters—the villainous German prison officer who has a caddish interest in the woman, etc. Bonhoeffer historians may raise an eyebrow at the fact Barr praises Eric Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer biography in her acknowledgments. Scholars have criticized Metaxas for his research and for presenting an Americanized Bonhoeffer where he seems to be a proto-evangelical. Given that this book was nominated for a Christy Award in 2020 (the Christy Awards primarily recognize fiction books released by evangelical publishers like Baker Books), it’s hard to escape the sense this novel fits broadly into the same camp as Metaxas’ book. It’s an American take on a 1930s German theologian, and that means it will emphasize his heroism over his flaws. Still, it does a good job of showing Bonhoeffer wrestled with what to do in these dark times. The book may not have the nuance and density of Erik Larson’s book about 1930s Berlin (In the Garden of Beasts). However, Barr does make it clear that, as Larson wrote, “these were complicated people moving through a complicated time…” Barr also does a far better job of avoiding WWII fiction stereotypes than many Christian WWII novels (for example, the cliché-laiden When the Heart Sings).

All told, Barr does a fine job. She combines biography, history, and some necessary fiction (imagining how conversations went, etc.) to make this story understandable and compelling.

A great novel about a unique romance.

Publication Information:

Rating (1-5 stars):

Four stars. Barr uses the WWII historical fiction framework masterfully. There are very few occasions where she falls back on clichés, and even then, Barr finds ways to get past the tropes and do something different.

Rating of Writing Style (1-5 stars):

Four stars. Barr weaves cultural details (father is “Vater,” coffee is “kaffee,” etc.) better than many historical fiction writers, making the German setting integral to this story about Germans falling in love while subverting their nation’s leaders. The historical facts mean this isn’t a very action-driven story, and Barr spends much time on introspection (characters thinking about their surroundings, feelings). This makes the book more melodramatic than some WWII historical romances, but that element feels natural and never bogs the story down.

Trigger Warnings:

Being a story about World War II, there are various discussions about Nazi violence (characters thinking about Jews being placed on trains, Gestapo verbally threatening people). None of these scenes involve graphic imagery. The main characters enter a romance that involves several kissing/dancing scenes, but never progresses to anything more sexual. There are a handful of scenes of a Gestapo officer making romantic overtures and intimidating a woman, which never progress to sexual violence.