BY G. CONNOR SALTER

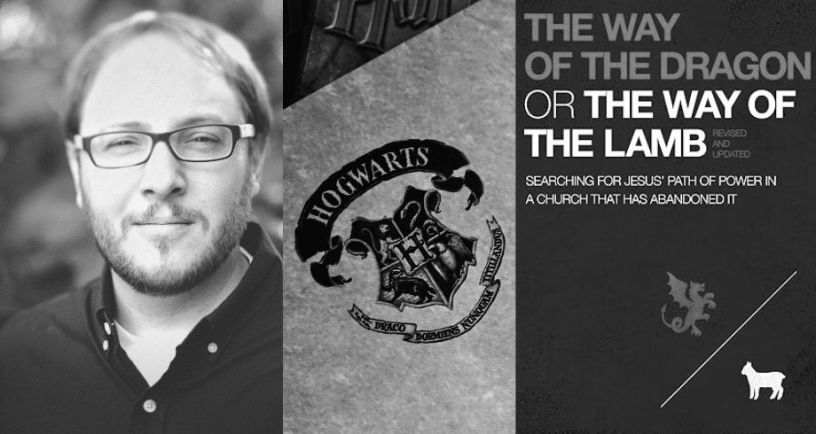

Kyle Strobel earned his PhD in theology from the University of Aberdeen, and has written extensively on philosophical and theological subjects. His many works on theologian Jonathan Edwards include Jonathan Edwards: An Introduction to His Thought (with Oliver Crisp) and, on Edwards’s spirituality, Formed for the Glory of God: Learning from the Spiritual Practices of Jonathan Edwards. He has also written Where Prayer Becomes Real: How Honesty with God Transforms Your Soul and The Way of the Dragon or the Way of the Lamb: Searching for Jesus’ Path of Power in a Church that Has Abandoned It (with Jamin Goggin).

However, he also speaks regularly about fantasy literature, particularly the Harry Potter series. His thoughts on the series have appeared on the podcasts Believe to See, Church Grammar, and Poema, and in writing for the Anselm Society.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

How did you discover the Harry Potter books?

I was a bit out of touch with popular books when they came out, focusing more on my studies, and so I ended up seeing some of the movies first. It wasn’t until I landed my first professor job that I decided to dedicate some time to the series. I was teaching students who grew up reading them when they were the same age as Harry, Ron, and Hermione. Since my students’ entire lives were lived against the backdrop of Harry Potter, I wondered if I could use the narrative to articulate the Christian Worldview, which was the main class I was teaching at the time. I was shocked at how deeply Christian they were since the movies tend to minimize that reality.

How did you make the shift from reading the books for lecturing to reading them for pleasure and then eventually writing about them?

I was captivated by Rowling’s narrative. I was surprised by how deeply they gripped me. She has a wonderful ability to depict things like evil, power, and friendship, and so the more I read them the more I was taken in with her explicitly theological purposes. This was all the more striking to me given how the church tended to respond to the books.

You’ve written about how crucial it is that the series presents sacrificial love and power as ultimately victorious over worldly displays of power. Do you think that gives the series a particularly Christian vision of what matters?

The central aim of the Harry Potter narratives is to describe how we all have to stand before death. How we do so – the path we take – will ultimately determine our humanity. This has everything to do with power. You write about magic when you want to describe how people seek power – what it is for, where it is from, and how you use it to advance a life – and so her narratives have a specifically Christian aim toward describing that reality.

This is why the book The Tales of Beedle the Bard is such an important companion piece to the series. If you haven’t read that, you can’t really see what she is doing in the series concerning magic. It turns out that it is true that we have to become like children to embrace the things of the kingdom, and so she offers a children’s book to unveil those secrets.

(Importantly, Dumbledore knows this, which is why he gifts this book to Hermione in his will. Hermione, in particular, with all of her book knowledge, must come to see a deeper kind of knowing that children embody so naturally.)

How do you think Rowling’s treatment compares to Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, where readers get another surprising vision of sacrificial love defeating lust for power?

Rowling certainly learned a lot from Tolkien and Lewis, and she is explicit about this. I think her unique brilliance is, in part, the developmental sequencing of the books, where the writing and depth of ideas grow along with the reader. So, it is hard to compare her work with others in that sense, especially given her reliance on them.

But I do think her series is closer to Tolkien than Lewis’ other two series (Narnia and The Space Trilogy), given her particular interest in power and how it functions. While Tolkien and Lewis both have “Death” as a kind of way of existence that warps the soul, she focuses on this idea to a greater degree and does a bit more with it. Because of this, I think, it leads her into depicting similar things as Tolkien, especially with heroes whose power is only discovered in and through their weakness.

Can you think of any Christian authors working today who create similarly compelling treatments?

Yes actually. There are some really wonderful series being done today. I think of Andrew Peterson’s The Wingfeather Saga and S. D. Smith’s The Green Ember series. Both are delightful. Smith’s is probably for a bit of a younger audience than Peterson’s books, but I loved them both. Like L’Engle’s series, Peterson picks up on the power of naming and being named, and that proves to be a profound theme for him, along with the recognition that we have to tell our stories, particularly our painful ones, in order for them to be redeemed.

You explored sacrificial love vs. worldly power in an ebook on Harry Potter, but you’ve also written about it in The Way of the Dragon or the Way of the Lamb. How did your treatment change as you addressed it in a new context?

I was originally asked to write the ebook as a “free giveaway” for The Way of the Dragon or the Way of the Lamb, which name biblical archetypes for the two contrasting ways of power. So, when I reread all of the Harry Potter books to write this, my focus was on the question of power as it was narrated by Rowling. I knew this theme was central from my previous readings, but I was surprised to find how central it was. This was when I was particularly struck by the biblical imagery and quotations in the books.

Articulating what I saw in Scripture about power through the Harry Potter narratives ended up being a really rich experience for me. It is one thing to name something Scripture says, but something a bit deeper to unveil it through characters in a story. My hope was to use these narratives, that so many know so well, to unveil a new constellation of imagery that could reveal what they didn’t have eyes to see in their prior readings.

Your article for the Anselm Society highlights how Harry walks a path that “is inevitably interwoven with death itself.” That’s a dark theme, but it does become redemptive. Do you think that willingness to do both, be somber and be hopeful, helps explain why the series is more compelling than many fantasy stories that try to be uplifting all the time?

I think that is right. One of the dangers of Christians working in the realm of literature and art is the temptation to avoid the darkness and pretend it isn’t around us. We live in the present evil age, and we, of all people, need to name evil for what it is. But many fall victim to what I call the “Kinkade heresy,”[1] where instead of using fantasy to lead us into the truth, one seeks to use fantasy to blind oneself further to what is really going on in the world. Good fantasy and science fiction should lead us to see the world we live in more clearly and to see it for what it is, and should not lead us to imagine the world was otherwise.

(John Comenius’ classic The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart,is a pietist allegory that seeks to name this theme, for any readers who want a spiritual classic that reads more like The Phantom Tollbooth!)

David Mathis observed in an article for Desiring God that most Christian critiques of the series disappeared once the series’ conclusion appeared and its final vision became clear. What are some ways Christians can avoid being too quick to judge trends?

I think it is important to name something that few do at this point. The obvious answer to the question, “Is the Harry Potter series dangerous?” is “Yes.” Of course it is. It is dangerous because we live in a theologically illiterate world, where people read these books and can only fantasize about doing magic. The mistake is to recognize the danger and then believe that banning them is the properly Christian response. Rather, the more dangerous thing we can do is to hand books to children and then never help them become actually literate people (or, worse, banning them so they read them in secret without actually talking about them). We should hand these books to our children and ask them questions, wondering with them about why each school year at Hogwarts revolves around Christmas, why 1 Corinthians 15 is etched into Harry’s parents’ tombstone, and why you become more snakelike when you give yourself to evil. Christians should see these books as an opportunity and not something to hide from.

Your interview with Church Grammar connected the way of the lamb/way of power discussion with the (sadly now very topical) discussion about Christian leaders misusing power. Does that demonstrate what we miss if we assume fiction can’t teach us spiritual lessons?

I think we have become blind to how Scripture describes power, and how it discerns the difference between worldly power and kingdom power. One side doesn’t bother to think about it, letting the ends justify the means, and so typically give themselves to cover-ups, toxic leadership, and all sorts of sinful behavior they think is justified by having a good doctrinal statement. The other side, equally foolish, demonizes power, as if we could have an adequate understanding of being human without power.

What fiction does so well is to teach us that there is a right way to embrace power, because there is a power that is uniquely the power of life and of love. Harry is on a journey to realize that he really is more powerful than Voldemort. He cannot initially believe it because he is still walking by sight. Harry, like us all, will have to grapple with the reality that we need to walk by faith and not by sight. Only when Harry begins to see that Voldemort has nothing to live for, and that he cannot know love or friendship, does he begin to see that there is a deeper way that Dumbledore has set before him. It is also significant, I think, that Dumbledore, undoubtedly powerful, consistently downgrades the importance of magic and always offers the fruit of the Spirit as more significant (kindness, as one obvious example).

This may be less true now, but in recent memory, evangelical Christians have favored adventure or fantasy stories that praise fighting for goodness but don’t delve much into avoiding worldly power. Movies like Braveheart, books like This Present Darkness became staples of Christian men’s conferences, but without much discussion about how to pair that yearning for justice with an understanding of the way of the lamb. Do you think the evangelical community is getting better at having that conversation?

I think so, even if only in pockets of evangelicalism. I think evangelicalism, out of a desire to make a difference in the world for Christ, has a tendency to embrace worldliness. The desire is a good one, but it ends up getting warped by methods that are antithetical to the cross. So, some of the interest in movies like Braveheart is akin to that. The overarching vision becomes, “Let’s dominate for Christ,” rather than, “Let us bear our cross and follow.”

Any upcoming projects you’d like to tell us about?

Right now I’m focusing on our degree programs in The Institute for Spiritual Formation at Talbot School of Theology. This has become such a rich community of prayer and vulnerability, and one of our constant discussions is about art, literature, and theology. We’re creating more spaces for this and so this has been a really exciting time.

More information about Strobel’s work can be found on Facebook, Twitter, and his Biola University profile.

[1] Interviewer’s Note: Thomas Kinkade (1958-2012) was an American painter known for his overly sentimental paintings. Karen Swallow Prior uses him as an example of how idolizing sentimentality damages the soul in her book The Evangelical Imagination.