BY AVELLINA BALESTRI

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your background.

I’ve been an incorrigible writer since childhood. I published my first short story at nineteen, and spent a lot of my teenage years writing abysmal science fiction novels, which I have since burned to keep them out of the hands of posterity. I eventually learned to channel my vice into a socially useful profession and became a technical writer. I tried other careers, but that was the only thing that stayed interesting. Since I retired, though, my congenital vice of writing fiction has returned and I am now inflicting historical novels and fairytale fantasies on a terrified public.

What first inspired you to start writing?

I don’t know. That is lost in the mists of childhood. I’ve been a writer as long as I can remember. It’s like asking someone why they drink too much or eat so much chocolate. It’s probably either a genetic defect or the result of some childhood trauma. My father was a professor of English who taught Shakespeare and the modern novel, so in my case it could have been either of those causes. I have tried to give it up several times, but I just can’t seem to quit.

And I firmly believe that this is the only reason anyone should ever be a writer. If you can do something else, anything at all, do that instead. It’s a lousy way to make a living, and there are far too many people doing it. Far more than the economy or the culture can sustain. Be a plumber. Be a doctor. Be anything other than a writer unless you just can’t stay interested in anything else.

How did you first become interested in history, and what are your favorite time periods?

I grew up on a cul-de-sac in Manchester, UK, and at the end of our street there was a railway line. This was at the time when steam locomotives (the most romantic form of travel ever invented) were being replaced by diesels (the least romantic form of travel ever invented). It was always a treat when a steam train came by. I remember me and my friends sneaking into the locomotive sheds where the decommissioned engines were being disassembled, and chatting up the workmen. They were as sad as we were to see the old machines being scrapped. But we learned a lot about how steam engines worked.

This was in the halcyon days when parents would let their children wander and no one bothered to mend holes in fences or fasten gates. It was the kind of childhood you can only read about in books today, and the librarians probably don’t want you reading those books either. In case it gave three nine-year-old boys the idea that they could wonder around railway stations and locomotive yards unsupervised and actually learn to take care of themselves and be back in time for tea.

Anyway, I got hooked on railways and the history of railways. And what you discover when you start studying railways is that transport is integral to every aspect of society. Railways quickly led me into all kinds of other things, from economy to politics to war. Transport is really the key to understanding any period. How easy is it for people to move around? What kinds of products can they transport at what costs? Those questions explain social structures. They explain administration and politics. They explain war and how it is fought, and why.

For example, transport is probably the most convincing explanation of why the Mediterranean world developed the way it did, and why other parts of the world did not develop as quickly. The presence of horses, navigable rivers, and a small, relatively calm sea with many civilizations scattered around its shores provided a unique opportunity for people to move around and meet each other. And that led to an exchange of ideas – which happens whether you are visiting or trading or fighting, but probably most when you are fighting. If you want to understand any place and time, study its transport and the consequences of it.

This interest led me to do an MA and part of a PhD studying the role of technology in the industrial revolution. Most of the explanation at the time were purely economic and essentially assumed that inventions just happened when the economic conditions required them. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” was a catch phrase of the era. I showed that this idea was bunk. Necessity can exist for centuries before invention happens. Not that anyone cared.

Curiously, these days I think people would shrug and say, well of course the causes were technological. That’s how we think these days. Then they looked at everything through an economic lens. Now we look at everything through a technological lens. Every age tends to have its pet theory that explains everything. Knowing what the pet theory of everything is for the period you are looking at is also key to understanding history.

That is actually one of the things I find most interesting about history: how people look for explanations with their own strange lenses, and the bizarre explanations they come up with in consequence. The internet has become a smorgasbord of strange wrong history.

Because I am interested in things like this, though, I don’t really have a favorite period. I’m often amused by people who say they would like to live in the past. I give them a week before they come crying back to the present. Most people have no idea how hard life was in the past. It doesn’t get said nearly often enough, but up until 200 years ago, something in the range of half of all children born died before they reached the age of five. And there were lots of ways to die after that as well. Consider that in a world without contraceptives, the population grew incredibly slowly. Think about what the death rate has to be for that to be the case. You don’t want to live in the past. And no, not even in the palace of Versailles.

For my fiction, I have dipped into different periods based on the stories I want to tell. Different times and places provide the perfect stage to tell a certain kind of story. For example, in The Wistful and the Good, Elswyth is engaged to one man but falls in love with another. Set that in the modern individualistic world and there is no story. She marries for love. The End. Set it in a world in which marriages are arranged to secure alliances and thus keep whole families and communities safe, and there is a story.

All that said, though, historical fiction readers, or at least, the publishing industry, has its favorite periods, and the Anglo-Saxon age is not one of them unless you name is Bernard Cornwell (as one agent told me in so many words). So for my latest work, I have shifted from the Anglo-Saxons to the Napoleonic period.

What started you on the journey of historical fiction writing in particular?

That’s a good question. I studied history from the beginning, from when I was a kid. And I grew up on Rosemary Sutcliffe, so I was well exposed to historical fiction. But all the awful dreadful horrible novels that I wrote in my youth were science fiction or fantasy. I think in those days I bought into the notion that to write a story you have to have an “idea.” So I wrote a fantasy about a boy who travelled around the world backwards while trying to get home. It was all about that “idea” and then all the ingenious ways I could come up with to make him keep moving in the wrong direction. It was awful.

I stopped writing fiction for a long time because I was too busy with other things. But once I came back to it, I realized that stories are not about ideas. Instead, all good stories are about moral dilemmas. They are about a choice between values. The “ideas” are just ways to force a character into a position where thy cannot avoid making that choice. And coming up with those kinds of ideas is not the hard part. The story problem is all about creating a convincing conflict of values for a believable human being. For instance, does Elswyth – not anyone, but Elswyth in particular, whoever she is in particular – marry for the alliance to secure her family’s future, or does she marry the man she loves. The dilemmas themselves are ageless. It is really all about creating a character who makes the reader feel like the dilemma is fresh for them.

And I think that once I figured out that that is what stories were about, history seemed like a more natural place to stage them than outer space. Which is by no means to suggest that this is universally true, just that it is true for me. (The said, SFF is the genre where the notion of the “story idea” is most common, and where the idea itself can sometimes carry a book.)

What are your favorite and least favorite parts of working within the historical fiction genre?

My least favorite part has to be the fanatical way that so many writers and not a few readers demand absolute fidelity to the historical record in everything. Put the wrong number of buttons on a glove and you will be banished to the outer darkness. And it is not that I think you should be sloppy about that stuff, but rather than being obsessive about it means that you are valuing historical fiction for the wrong thing.

I often ask people, what if there was a great historical novel, a literary classic, and new research showed that the events in the novel did not happen the way it says. Would that make it a worse novel? It’s surprising how many historical fiction readers and writers either say it would make it worse, or hedge and refuse to answer. If you are valuing a novel for its value as a history text, you are valuing it from all the wrong reasons.

There are, of course, many historical novels and films that outright lie about the past, and that is reprehensible, because it is lying. My attitude is, the novelist is under no obligation to tell the truth about history, but they are under a firm obligation not to lie about it.

Anyway, the point is, historical fiction is not a good way to learn history. It always falsifies the past, if only by making things seem far more certain and clear cut than they really were. Novels have a different purpose. History provides many stages on which to set many stories, but it is quality of the story, not its capacity to serve as a textbook, that we should be looking at.

I would say that my favorite part is the ability to find the perfect stage for exploring a particular theme or telling a particular story. Modern civilization is designed to take the drama out of life. And that’s a good things. I’d rather find my drama in books than in the streets. But the lack of drama, particularly physical drama, in modern life means that authors turn to trauma for their drama, and while there is a place for that, there is currently a gross excess of it, and it is often crass and exploitative. My response is usually, stop moaning and go on an adventure already.

How have you chosen which historical characters to feature in your books, and what made their stories resonate with you?

I’m not a tales-from-history kind of writer. I use history as a stage to examine a theme. All of my characters are inventions. King Eardwulf in St. Agnes and the Selkie and The Needle of Avocation shares a name with a king of the same period, though none of his character or personal history. (Actually, we know nothing about the real Eardwulf’s character or personal history. He is a name on a list of reigns.) Apart from that, every character is an invention.

What is your process in terms of research and bringing historical characters to life?

I’ll start with a couple of survey texts on the period and then research as I go. The biggest problem for historical novelists, I think, is knowing what to research and when. I remember reading one manuscript in which the author had an stage coach spinning its wheels in the mud. Well, of course, no vehicle spins its wheels unless they are driven by an engine. If you get a stagecoach wheel in mud, it just sinks. The author was clearly projecting a modern experience into the past without thinking it through. You have to develop an alertness to that kind of thing, which comes from an sound general background in history, combined with a good sense of the plausible. If you can develop that, then you can research topically as you write. If you don’t develop it, you can research till you are blue and you will still make mistakes of this kind. Actually, we probably all make mistake of this kind from time to time. The trick is not to make the ones that are easy to spot.

But when it comes to characters, the great thing is to really understand the milieu in which they lived. We talk about judging people by the ideas of their own time, but there is an arrogance in that, a sense that we are so much better now than they were in the past, and so we have to make allowances. That’s nonsense. Humans are horrible. They were horrible then, and they are horrible now. We are only nice under certain limited conditions. The difference is that today we are so much richer, and so those conditions occur somewhat more often. Our extraordinary wealth makes the present unlike the past. For instance, today we regard liberty as the norm and bondage as an abomination. But for almost all of history, bondage was the norm and liberty was a privilege won by service.

Similarly, we regard individualism as a social ideal and universal aspiration, and any kind of obligation to family or society as something to be cast off. But that kind of individualism requires lots of money, safe streets, reliable banks and courts, and the ability to work for an institution for money so that you can buy food and lodging from another institution for money. If those conditions don’t exist, you need a family with strong obligations to you which you return with strong obligations to them. As an historical novelists, you need to clearly understand that for any period outside the last 200 year, and sometimes much less than that, society was made up of families, not individuals, and people’s social position was defined by those to whom they had obligations and from whom they received the necessities of life. If you understand that, you have the starting point for imagining an historical character.

And, of course, look at the transport, because transport is wealth and transport is mobility. Individualism without effective transport makes no sense. What we call individual liberty, most societies called exile. Exile is great if you have the money and safe streets with an effective police force. Without those things, it is a death sentence. Safety lies in the tribe.

Consider too that transport governs what percentage of people you meet every day who are strangers. If you live in a modern city, a very high percentage of the people you encounter are strangers. They look different. They speak differently. They worship differently. In most periods of history, even for people living in cities, most of the people they met in a day were known to them. Strangers were rare, and strangers who looked or spoke or worshipped differently were even more rare. This makes leaving home a much more terrible prospect than it is for a modern person. And it makes an enormous difference to how you greet a stranger if you haven’t met anyone you don’t already know in the last three years.

What is your method to integrate fictional characters and situations into the historical setting?

This is where you have to look into what I call the deep ground of history. In my Anglo-Saxon books my characters are on the lowest rung of the nobility. They keep slaves. They keep slaves not because they don’t know better or because everyone else kept slaves too. They kept slaves because transport was poor, everyone lived on the land, and everyone depended on one another. Everyone was bound, from the slaves to the nobles to the so-called freemen, to the king. Degrees of liberty and wealth could be won by service, and it was possible to move up in society, even for a slave. But the slaves were simply the lowest rank with the fewest privileges. The whole notion of individual liberty does not arise until you get a larger and more developed middle class.

Another thing to remember is that we are a tribal species. Studies show that we are capable of having personal relationships with about 400 people. After that everyone is effectively a stranger. If you live in a rural village with poor transport, your tribe, your 400 people, include young and old, weak and strong, wise and foolish, healthy and sick, sane and mad. You have to get on with all of them, because there is no one else to be your tribe. Today, most of your 400 are probably people very like you that you know online. You have far more in common with them that someone in a tribal village had with their tribe. And therefore you don’t have to learn to accommodate yourself to the variety of people in a tribe you cannot change. You can change your tribe at will, and isolate yourself from anything and anyone disagreeable. You are going to have a very different set of social skills, and a very different set of affections and hatreds than the person in a village tribe who has to get on with everyone around them, but hardly ever meets a stranger or has any clue that other people live differently.

You have to be constantly asking, what shapes this person’s milieu. In particular, what makes them feel safe and what makes them feel unsafe. Because it is when we feel safe that we are nice, and when we feel unsafe that we are horrible. And yes, people who have never had to deal with anyone who isn’t just like them feel unsafe a lot of the time and behave horribly as a result. The modern examples are obvious. We need to think through the historical equivalents.

If you had the chance to convey a message to your favorite historical characters, what would it be?

I’d tell Thomas More to get out of England before Henry’s men came to arrest him. And take Bishop Fisher with him.

What do you find more enjoyable/difficult: First drafts or editing/rewriting?

Oh, first drafts. That’s where the story happens. It’s where you meet the characters. After that its all just slog. But I am not someone who believes in the crap first draft. I think that is a pernicious idea. It’s true that if you are writing a novel for the first time that your first draft will be crap, just as when you ride a bicycle for the first time, you will skin your knees. But that is not how you should aspire to write. Characters are formed and events crystalize as you write the first draft, and there will be elements of those characters and events that will stay with you for a long as you work on the book. If you don’t get them right in the first draft, you will be struggling with them and compromising with them through every rewrite and the result will never be as fluid or organic as if you had got them right the first time. So I really urge people not to spew out a crap first draft and then try to fix it later. You wouldn’t approach any other project like that. Don’t do it with you writing. Take the time to really think through your story and make the first draft as good as it can possibly be.

How have you gone about publicizing yourself and your works?

I have gone about it extremely badly. I forget that I am supposed to be doing it for weeks at a time and then do random stuff in a panic. It seems like marketing and publicity requires doing many small things and keeping track of them all. I am hopeless at that. If anyone has any advice, I’m listening.

What are some of the main themes/morals you would like readers to take away from your works?

I hate moralizing fiction. I hate it with a blue blinding passion. I regard it as a corruption of the form. You might as well be a moralizing plumber or a moralizing pastry chef. The job of the novelist is to tell a truthful story about human experience. And since as Catholics we acknowledge our universal sinfulness in this our present exile, the job of the Catholic novelist is to tell a truthful story about sin and sinners.

The problem with moralizing fiction is that it almost always lies about human experience. It lies about sin and it lies about virtue. People turn to moralizing fiction for affirmation of their own imagined moral superiority. Moralizing fiction encourages an unhealthy pride in the reader. It is a corruption of the form, and thus immoral in itself. It’s like the plumber making the pipes leak because he disapproves of the lifestyle of the householder, or the pastry chef making nicer cakes for the customers they like. These are both betrayals of their respective professions. Cobbler, stick to thy last. Novelist, tell the truth about human experience.

There is a place for moralizing. Priests and editorial writers should moralize. It’s their job. But not novelists. Not because moralizing is wrong, but because it is not our job.

What is some advice you would give aspiring authors, especially those focusing on the historical fiction genre?

Become a plumber instead. It’s good money, steady work, you will get to meet and work with other people. And the world needs more plumbers. Being a novelist means lousy money, unreliable work, and solitude. And the world does not need more novelists. There are far too many already. If you have to be a writer, if nothing else will satisfy, be a technical writer. It is good money, somewhat steady work, and you will get to meet and work with other people. And the world needs good technical writers. But if there is any way you can possibly avoid it, don’t become a novelist.

If there is no way you can possibly avoid it, then take the time to understand the publishing industry. And I don’t just mean to understand about query letters and contract. I mean learn about how books are chosen and how they are edited to fit certain vertical markets. Be very clear in your mind whether you are willing to produce the specific types of product the publishing industry is looking for at the moment. I see so many people posting on forums saying, “I have just completed a 300,000 word historical fantasy about a shepherd in 9th century Siberia. How do I find a publisher?” To which the only answer is start again with a project that actually has a chance of selling. Or publish it yourself.

This does not mean that you have to write to market. The market is in a horrible place right now, and the ideological capture of the big publishing houses means that a large chunk of the reading public is not being served. But at the same time, understand the relationship between art and commerce, and don’t suppose that you can ignore commerce all through the writing process and still expect to find a publisher. If you can find some overlap between what you are interested in and capable of writing about and what some publishers is publishing, go for it. If not, be prepared to self-publish. Or become a plumber. Becoming a plumber is a much better idea. I wish I was interested in plumbing.

Plug your socials, published works, and current projects!

My main social media is my newsletter, Stories All the Way Down, which is at https://gmbaker.substack.com. You can also find me on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/gmbaker/ and LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/mbakeranalecta/. My website is https://gmbaker.net.

My published works include:

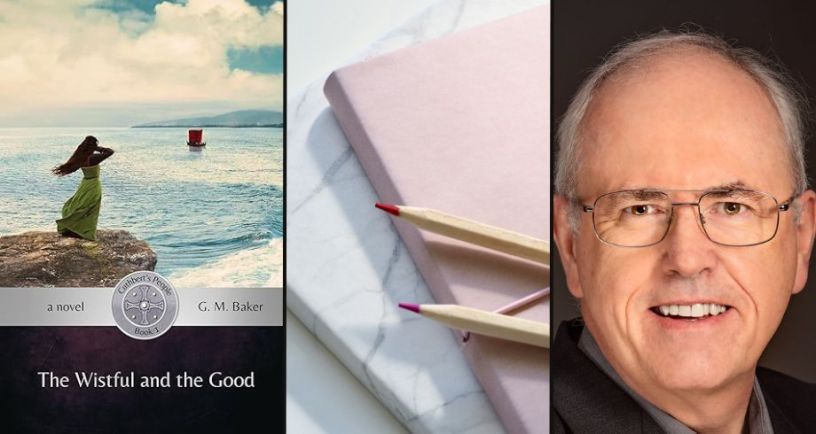

- The Wistful and the Good (historical novel, 8th century Anglo Saxon)

- St. Agnes and the Selkie (historical novel, 8th century Anglo-Saxon)

- The Needle of Avocation (historical novel, 8th century Anglo-Saxon)

- Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight (fairytale/dark fantasy)

- The Four Constraints of a Catholic Novelist (essay, Dappled Things)

My current project is an historical novel set in Cornwall in the Napoleonic era called The Wrecker’s Daughter about a young woman who works in the family business of wrecking ships, murdering their crews, and stealing their cargos.