BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Gina Dalfonzo brings interesting observations to many topics. Her work ranges from articles about Olympic skating to reflections on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. These articles have appeared in such places as Christianity Today, Christ & Pop Culture, Aleteia, The Atlantic, Plough Quarterly, and The Englewood Review of Books. She also edits Dickensblog and runs a biweekly book review newsletter Dear, Strange Things.

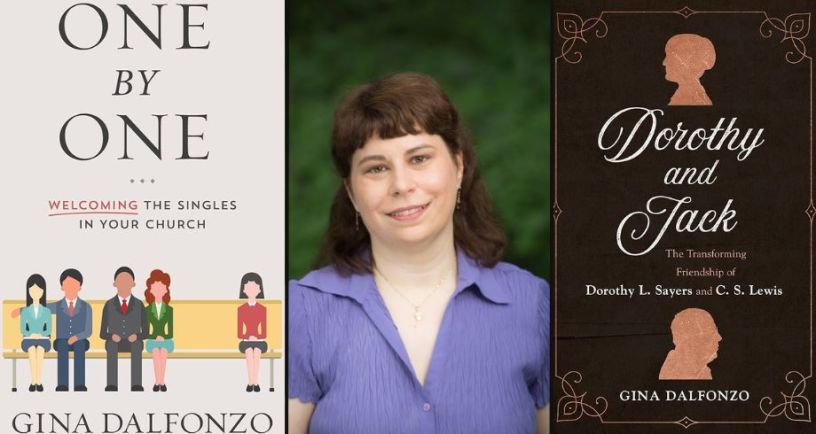

Her books include the anthology The Gospel in Dickens: Selections from His Works, Dorothy and Jack: The Transforming Friendship of Dorothy L. Sayers and C.S. Lewis, and One by One: Welcoming the Singles in Your Church. Her upcoming book will explore a new area: movies.

She was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

How did you become interested in writing?

When I was a child I was interested in all kinds of potential careers—ballerina, concert pianist, veterinarian—but somehow I always circled back to writing. It was one thing I just kept doing consistently and enjoyed doing. Eventually it dawned on me that it was what I was meant to be doing!

You’ve written a lot about classic authors who inspire you—from Charles Dickens to Dorothy Parker. Are there any authors you admire who you wish were better known?

I’m always telling people to read H. G. Parry, a wonderful New Zealand writer of historical and literary fantasy. She’s published four novels so far and I love them all, but my favorite is her first, The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep—as you can tell from the title, she gets lots of good Dickens references in there!But all her novels are written with great imagination, wit, and heart. As I’ve said elsewhere, she made me cry over William Pitt the Younger (in her novel A Radical Act of Free Magic), a historical figure to whom I’d never given much thought before. That speaks to how moving her writing is and how well she brings her characters to life.

It’s clear from reading your work that you enjoy classic stories. You’ve also written about what happens when adaptations of classic material—whether it’s modern updates of Jane Austen novels or new movie versions of Much Ado About Nothing—miss the mark. What are one or two key things you suggest we need to remember when exploring or adapting a classic work?

It’s a fine line to walk. As I mentioned in that Austen piece in particular, one thing that makes a work a classic is its author’s ability to faithfully portray his or her culture and at the same time critique it. This both grounds the work in its own time and makes it timeless. So a good update should be able to do something similar, but while it’s portraying its own time, it also has to connect with the original work that was portraying its own time! A recent update that does all this successfully is Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver’s update of David Copperfield. It’s very gritty, with several of its characters, including the young hero, trapped in toxic relationships and ravaged by opioid addiction. Yet even as its characters experience Dickensian levels of poverty and misery, the story also reaches a Dickensian level of hope. There are disconcerting modern elements in it (a lot of profanity, for one thing), and yet it still reflects the spirit of the original.

You make some astute observations in your introduction to The Gospel in Dickens about how Dickens’ ire against Christian characters is usually criticizing them for hypocrisy. Has that clear-eyed depiction influenced your faith?

Yes, I believe it has. It reminds me that not everything that calls itself Christian really is, that you have to look for it among the poor and meek and not the glitzy and ostentatious—as Jesus frequently told us! Also, the fact that Dickens still believed despite being aware of all the hypocrisy and other sins reminds me to see the big picture and remember how much good there still is in our faith.

Plenty has been written about C.S. Lewis’ male friends in the Inklings, less about people outside that circle. How did you become interested in telling the story of his friendship with Dorothy L. Sayers?

This friendship was something I had known about ever since I took a college course on the Inklings and their friends. But I came to realize that not many people in general knew about it. Interestingly, their fandoms tend not to overlap that much—she’s better known among readers of detective novels, and he, of course, among readers of theology, fantasy, and/or children’s novels. So even the biggest fans of each aren’t always aware of how well they knew each other. But I was such a great fan of both that I wanted to dig deeper into their friendship and their correspondence and share it all with others. I was really fortunate to get the opportunity to do that, and I enjoyed it so much.

One thing I appreciated about Dorothy & Jack was your boldness in pointing out Lewis and Sayers weren’t perfect. Sometimes they made choices that were unfortunate in hindsight, like disregarding stories about Charles Williams’ behavior with women. When did you realize the book was going to have to address their flaws as well as their strengths?

Oh, I knew it all along. You can’t tell someone’s story properly without showing the bad as well as the good. It would be only half a story. And it would also be unrealistic and dishonest. The good thing is, you can often learn as much from someone’s mistakes as you can from their virtues! And in the case of these two, another good thing is they learned from their own mistakes. Because they both took their faith and its teachings on sin and redemption seriously, they were able to recognize many of their own flaws, repent, change, and grow.

Earlier this year, I got to interview Williams scholar Sørina Higgins, and we discussed the need to overcome seeing the Inklings and their friends as “great evangelical saints.” What has help you see them as people in all their complexity (the good, the bad)?

A moment ago, you mentioned the section in the book about their unwillingness to see the whole truth about Williams (something that Sørina has done a great job writing about, incidentally). That was one thing that helped, because I was reading about this at a moment when our contemporary culture is taking stock of how long we’ve tried to sweep such behavior under the rug, and how that enabled the perpetrators to keep doing it. So while I could see it was hard for Sayers and Lewis to believe something bad about a good friend, I also had a helpful perspective on how damaging such an attitude can be.

Many fans of Lewis and his circle tend to decry all things modern, and in some ways that’s perfectly understandable. Our modern culture can be very shortsighted and closeminded. That’s why, for instance, Lewis suggested reading one old book for every new book we read, “to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds.” It’s an excellent rule. But it works the other way around as well. We need to be aware of new attitudes and ideas and find what’s good in them even as we remember to keep absorbing what’s good from the past. And I think that ultimately helps us look at the past with greater understanding.

How has your journey facing Sayers’ and Lewis’ complexity compared to your journey facing Dickens’ complexity—someone you write about regularly?

What a great question! I think learning about Sayers and Lewis, warts and all, helped me to do the same with Dickens. Because when I was younger, I did tend to put my favorite authors and historical figures on a pedestal—I didn’t want to face the fact that they had any faults at all. But I had a good professor, Dr. Robert Ives at Messiah University, who introduced me to Sayers and Lewis and their circles, and he taught about them in ways that helped me see that you don’t have to put someone on a pedestal to admire and love them. You can allow them to be human. In fact, it’s better if you do.

Dorothy and Jack and your earlier book, One by One, both explored how often Christian groups prioritize marriage in ways that create problems for whatever doesn’t fit that label. Looking at the situation now, do you think American evangelicalism is getting better at having that conversation, or do we have a long way to go?

Yes and yes! That is, I see more and more Christians talking about it in honest and healthy ways and seeking to make things better, so yes, the conversation is getting better. But I still see some truly unfortunate bias against single people, sometimes in very prominent places, so we do have a long way to go. (For instance, there are some Christian thought leaders and even a couple of politicians who have said they’d like single women’s votes to count for less!) It feels like a long slog sometimes, but all we can do is keep sharing and asking people to listen. Slowly but surely, and despite the pushback, I do believe we’re getting somewhere.

What can you tell us about your latest book?

I’m really excited about it. It’s about movies, so it’s something both new and old for me—I talk about movies all the time (just look at my Twitter), but I’ve never written a book about them before! The working title is The Screen and the Mirror, and it’s about watching movies in a way that teaches us about ourselves and shows us our need for redemption. (So in a way you could say it connects back to Dorothy and Jack and The Gospel in Dickens, with that warts-and-all approach!) The book traces this theme in the original Manchurian Candidate, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, The Godfather, In the Heat of the Night, Knives Out, and several more. My manuscript is due in January 2025, so look for it from Cascade Books sometime after that!

Recently, in an Inkling Folk Fellowship event where you talked about your book, the conversation led to different decades of filmmaking. What is your favorite decade?

I truly don’t know if I can narrow it down to one decade! I really have three favorites. The 1930s had so many groundbreaking classics in various genres—crime and detective films, musicals, epics, romantic comedies—but then the 1940s had some truly special films like Casablanca, It’s a Wonderful Life, The Best Years of Our Lives, and so many more. And then in the 1950s, along came my favorite actress (Audrey Hepburn) and my favorite film (Singin’ in the Rain). So I don’t know how to pick just one of those decades! They’re all so good!

More information about Dalfonzo’s work can be found on Dear, Strange Things or on her Facebook page.