BY G. CONNOR SALTER

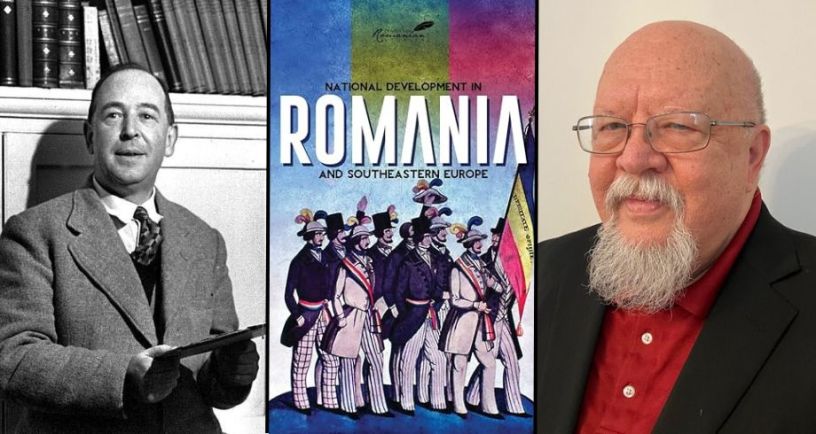

Dr. Paul E. Michelson (PhD, Indiana University Bloomington) brings an unusual approach to Inklings studies. He earned his doctorate specializing in South East European history and has worked extensively in Romanian history. His many contributions to that field include writing the book Romanian Politics, 1859-1871: From Prince Cuza to Prince Carol and contributing to the books A History of Romania and Encyclopedia of East Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism.

His articles on C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and related figures have appeared in many publications, including Linguaculture, Christian History, and Inklings Forever. He has also written about and supported the growing community of Inklings fans in Romania. He is a founding member of the C.S. Lewis & Kindred Spirits Society for Central and Eastern Europe.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

How did you discover the Inklings’ work?

When I was a freshman in college in the fall of 1963, the college church group I attended decided to read Mere Christianity. This was two months before Lewis died. I was not taken with Mere Christianity, probably because I was reading the wrong philosophy books. “What are they teaching them?” as Professor Kirke asked. I could tell you if you had the time, but in short, most of it was the kind of pop-elite culture books and articles we still have around today: the latest memes, trendy stuff in trendy elite journals that five years later would be completely forgotten, but would have—as Lewis put it in The Abolition of Man—stolen little bits of the Western heritage from us.

I had a pretty strong Christian faith, but I don’t think the idea of the integration of faith and learning was part of it as such. Christianity was one thing and the general culture was another, and the twain did not meet except where the culture made a frontal assault on orthodox Christianity (such as the God is Dead movement). Such onslaughts were recognized as bad but not necessarily part of the cultural “soup” we were immersed in. These attacks, of course, led to lots of heated discussions with less orthodox pastors and students in other campus religious groups (what we would probably call “mainline” today). So, we were in the conflict on the theological front, but I don’t think we saw that the same thing should be happening on the philosophical, cultural, and educational fronts.

Later, my soon-to-be fiancée (later wife) and I would meet in the children’s literature section of the college library and read the Narnian books together. I don’t recall who recommended this, but God bless them. Then one of the philosophy profs gave a lecture to our college church group on the philosophy and theology of Narnia, which might have been a first insight into the faith and learning issue/problem. We also learned a lot more about Lewis’s other commitments and hats.

At about the same time, J.R.R. Tolkien erupted as the literary phenomenon du jour. At a student conference, I met several people with considerable obvious intellectual attainments who were animatedly reading and discussing The Lord of the Rings. It didn’t take me long to discover why. It was, I think, typical that I was totally unaware that Tolkien and Lewis had anything in common, possibly because most of the Tolkien aficionados I originally met were not particularly Christian and probably had little or no interest in Lewis.

Then when we went off to graduate school in Indiana, it was much clearer. While one is heavily focused on the field or fields of study, one has to have outside interests. The Sunday School class at the church we now attended was full of graduate students and spouses who were highly interested in and pursued faith/learning matters. We still didn’t call it that, but looking back that’s what it was. My outside reading hobby became C.S. Lewis who seemed to be interested in the same questions. Mere Christianity now made more sense and I bought and read through all of Lewis’s books while toiling away in the history of Eastern Europe, Russia, and Western Europe. In the process, I read Lewis’s sci-fi trilogy, which led me back to Tolkien.

Did your academic interest in the Inklings come before Romanian history, or vice versa, or have they always been in tandem?

Obviously, I was a historian first and only peripherally interested in Lewis and Tolkien, who were more of a hobby or an entertainment. It was only much later when I had begun to teach on them at a midwestern Christian college—now Huntington University—that an academic interest in the Inklings developed. They, evidently, had been encountered in connection with reading Lewis and Tolkien and reading about them. I also taught a couple of January (short-term) courses that dealt with them, their lives, and their work. Several of these courses involved trips to the Wade Center where we were received and enlightened by that gracious and congenial Southern gentleman and scholar, Clyde S. Kilby.

How did you choose Romanian history as your research subject?

The short story is I was interested in nineteenth-century Europe. I figured Western European countries would have been pretty well covered by their own historians, leaving more minute topics. But because Marxism imposed a specific approach to history and specific conclusions, it turns out that pre-1989 East European communist countries had a lot of very significant topics that were either ignored or falsified. It was a good decision because right from the start, Romanian historians were interested in what I was doing and, in a number of cases, quietly encouraged my work.

You were recently part of a wonderful discussion hosted by the Inkling Folk Fellowship about the C.S. Lewis & Kindred Spirits Society and its efforts to promote Lewis’ work. For the benefit of those who don’t know, how did C.S. Lewis catch on in Romania?

Obviously, a conservative, Christian, bourgeois writer like C.S. Lewis would not be published or studied in Communist Romania. Mere Christianity was translated into Romania and sneaked into the country as were Bibles, but these were hard to get ahold of. After the fall of Communism in 1989, a few things, including The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe were translated and published. A number of Romanians were quick to point out that Narnia’s White Witch bore a lot of similarities to the co-dictator of Romania, Nicolae Ceaușescu’s wife Elena, which increased interest in Lewis. The big breakthrough owed to the fact that the co-owner and editor-in-chief of post-1989’s most prestigious and largest publication house had become acquainted with Lewis’s writings when he spent a year on an exchange fellowship in West Germany. His publishing house has steadily been translating and publishing most of Lewis’s books except for the two literary histories, and Narnia, which was published by the leading post-1989 sci-fi fantasy publisher.

Secondly, English literature scholars at the University of Iași in North Eastern Romania became interested in Narnia and then the Inklings and started teaching an occasional course on these subjects. One of them, Rodica Albu, was the first translator of The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe in the 1990s. One of their graduate students (whose dissertation was the first on Lewis in Romania), a woman named Denise Vasiliu, got a grant to study at the Wade Center in Wheaton and was introduced by the then-Director Christopher Mitchell to American and British Inklings scholars, including Jerry Root, Michael Ward, and Walter Hooper. Dr. Vasiliu was inspired to organize the first C.S. Lewis conference in 2013, and convinced Michael Ward and several other Westerners to attend—including the then-British Ambassador to Romania, Martin Harris, who talked about how Lewis had affected him and displayed his own battered childhood copy of The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. These conferences have continued to the present, the sixth of which was in the winter of 2023.

What are some reasons that Lewis and other Inklings have resonated with Romanian readers?

Apart from how the dictatorial regime in Narnia and in Communist Romania resonated, Lewis and Tolkien are popular there for many of the same reasons they and the Inklings are popular anywhere: Romanians like sci-fi and fantasy literature. Romanian Evangelical Christians find encouragement and apologetic help from Lewis’s writings. Lewis’s non-denominational “Mere Christianity” means that he can be read by Evangelicals, Roman Catholics, and Romanian Eastern Orthodox (80% of the population is Orthodox), and have provided the basis for inter-faith dialogue between conservative, traditional believers. Tolkien, because he is not overtly Christian in his work, is even more successful and popular in Romania; occasionally, people find the link to the Inklings and thence to Lewis, which is all to the good. The other Inklings are much less known, but there is a growing acquaintance, especially because of the CSLKS.

I’m glad you’ve brought up the CSLKS. How did you become involved with the group?

I became aware of these efforts only in 2018 since most of my Romanian colleagues and friends were historians and did not overlap with the early 2010s start of the movement. I was at the Wade Center in Wheaton and Marge Mead asked if I knew the Vasiliu family. I did not, so she put me in touch with them, with the result that I attended the 2018 conference and participated in the organization of the C.S. Lewis and Kindred Spirits Society that preceded the conference. It turned out that my academic work in Romania previously had prepared me to link up with their Romanian networks, and I have been an enthusiastic supporter of the CSLKS ever since.

Several members mentioned in that IFF event mentioned kindred spirits like George MacDonald. Who are some kindred spirits you would love to see get explored more?

There is room for all of them at CSLKS, possibly MacDonald first of all because of the breadth of his work and the fact that we have several very active members. Charles Williams’s novels would reach the sci-fi crowd and some of his theological works on Dante and other subjects could reasonably be translated and published. There is a lot of potential for more about Owen Barfield and Dorothy L. Sayers. Chesterton has been translated into Romanian (Father Brown and other fiction); I dare say quite a few of his other works would be feasible as well. The last two or three CSLKS conferences have had a steadily increasing number of papers on all of the above; this, in turn, will spur future interest and study. (Two volumes of conference papers have been published to date and a third will appear this year.)

Has interacting with Eastern European fans of the Inklings taught you things that you didn’t expect? For example, do they bring new interpretations to the text that challenge you?

Well, there is always the influence of the historical context in which Eastern Europe has existed and exist. Naturally, this lends itself to difference perspectives. Since I have spent 50 years studying the East European context, I am less surprised by how some of this comes out in Inklings interpretations. And on the other hand, I have probably thought less about this than other things, such as the basics of Lewis’ thoughts, or other Inklings related topics, and perhaps need to give more attention to this in the future.

This may have been less true before the 1980s, but it seems like Midwestern Americans have built a huge Inklings market. There’s the academic side (the archives at Wheaton College and Taylor University) but also a popular side that loves using Lewis for inspirational material. For example, Grand Rapids in Michigan is filled with Christian publishers releasing books every quarter with titles like 10 Lessons from C.S. Lewis on Hope. Speaking as an Inklings scholar who’s lived in the Midwest for some time, how do you feel about that commercialization?

I don’t think it’s necessarily bad, especially if it gets people to go back to the sources and reading what Lewis, Tolkien, and the others actually wrote themselves. I don’t have a very high opinion of the three Narnia movies that have appeared so far: The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe was the only movie that one could watch without too much anguish, but I was under-whelmed and astonished that some novice screen-writer thought he knew better than Lewis how to write or plot a story; Prince Caspian’s decision to appeal to the adolescent market was an incoherent failure since it disgusted most serious Narnia fans without winning over the teeny-bopper demographic; Voyage of the Dawn Treader’s butchering of the story has only one evident virtue, that of making the first two movies seem better than they were. And there is the fact that all three do a pretty thorough job of erasing or obscuring any Christian themes that might have been present.

Anyway, I don’t think the bad money in Lewis and Inklings studies necessarily drives out the good. At the very least, a bad book on Lewis is likely to have lengthy quotations from Lewis. What can be bad about that? People might be drawn to actually reading Lewis. This reminds me of an interesting phenomenon in Communist Romania. A book came out attacking Christians (surprise!). The book, I was told, sold pretty well, but not for the atheist stuff. The book had quite large portions of the Bible adduced to proved its worthlessness. But, people were buying the book to cut out the Bible passages and paste them into notebooks for devotional purposes since actual Bibles were difficult, if not impossible, to obtain. Ha, ha. One fantasizes that the Marxist mastermind behind publication of that book got fired for producing reverse propaganda. And it can’t be ignored that people with a fanboy interest in Lewis and Inklings studies are often the largest audience for courses and other serious stuff and may push on to greater depth. As for inspirational material, I rather think Lewis and the Inklings can be inspirational.

It’s been suggested that Eastern European countries became especially interested in fantasy during the USSR era, perhaps as a means to dream and explore ideas outside the system. Any thoughts on that?

I did a paper on “Inklings in Eastern Europe (especially in Russia and Romania)” for the 2023 Inklings in Indy conference and, to some extent, this is true. Of course, reading anywhere is, in general, a route into some other reality. Tolkien said that faërie stories are escapist and that there’s nothing wrong with thinking about escape when you are in prison. Soviet states were in fact giant prisons and fantasy would be an escape. The same would be true for great literature: Gulliver’s Travels, Shakespeare, and so forth.

Sometimes conversations about fantasy and sci-fi start by talking about how those works can explore authoritarianism’s dangers, and give the impression they give better ways of exploring those questions then straight journalism. Do you think there’s a false dichotomy there? Can we learn to cherish Tolkien’s descriptions of Saruman’s dangerous authoritarianism and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s journalism about the gulags, even though they use different methods to discuss the same dangers?

This would be the start of a rather long discussion that we should pursue elsewhere. In short, there are both true and false dichotomies. Sometimes, hyperbole is needed to make the truth sink in. “Better ways of exploring”? Sometimes, but I wouldn’t want either/or. You probably need the non-fiction material to understand the fiction. Does One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich do a better job of portraying reality than The Gulag Archipelago? For some, the point will sink in better from one than the other. But we need both. Solzhenitsyn published One Day long before Gulag, but his entire Russian audience knew about the latter from firsthand experience and didn’t need a book about it. Westerners, who were incredibly ignorant about the Gulag even though it had been around since the 1920s, do need books on it.

Any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

Well, I’m mainly trying to finish a bunch of Romanian projects and books that have percolated too long. I have been asked to put together a little book about the life and ideas of Lewis for a Romanian audience (not one of the aforementioned projects) as an introduction to CSL. We’ll see. I also have three essays on stories about CSL, Tolkien, and Sayers, which I think would make a nice little book. And I have several essays, published and not, about Lewis-related subjects that could be a nice book.

What are some ways that people outside Romania can help the C.S. Lewis & Kindred Spirits Society?

CSLKS is trying to build a regular network of contributors so that the amazing projects they are pursuing in Iași don’t have to go from hand to mouth. I can’t think of a more deserving project to support if you are an Inklings advocate and see the apologetic opportunities that are there. If you are interested in more information about CSLKS, I have a recent “history” of the project you can download at this link: http://pmichelson.com/michelson_csl comes to romania 2022.pdf.

More information about Michelson’s work can be found on his website. Readers interested in hearing more about the C.S. Lewis & Kindred Spirits Society can be found through the Agora Christi Facebook page. Donations to the group can be made through Faith & Learning International.