BY G. CONNOR SALTER

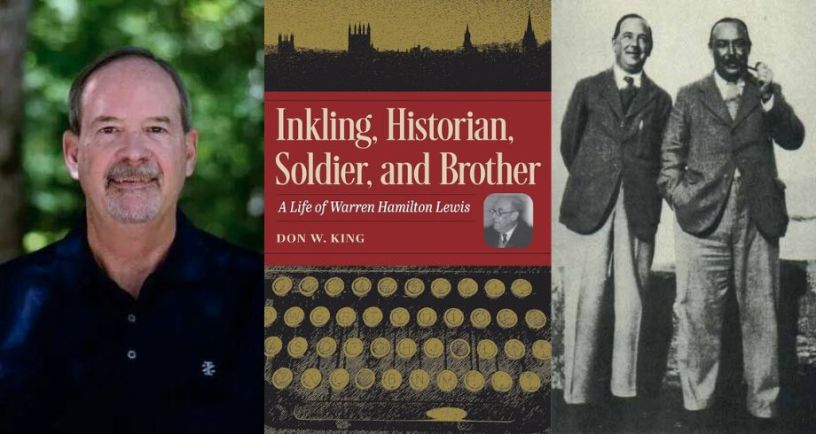

Dr. Don W. King (PhD, University of North Carolina at Greensboro) teaches British literature at Montreat College. He is a well-known scholar on the Inklings, particularly known for work on under-discussed areas of Inklings scholarship, such as C.S. Lewis’ poetry.

In this second part of our interview, King discusses C.S. Lewis’ older brother. Warren “Warnie” Hamilton Lewis was close to his brother (or “Jack,” as family and friends called him) throughout their lives, managing Lewis’ correspondence and sharing a home with him, The Kilns, in Oxford. Much has been written about his difficult relationship sharing the home with Mrs. Janie Moore, the mother of Lewis’ World War I colleague Paddy Moore. Lewis had promised to care for Paddy’s mother if Paddy died in battle, and Mrs. Moore lived with the brothers at the Kilns until her death in 1951.

Warnie attended many of the Inklings’ meetings, wrote multiple books on French history, and contributed to Inklings scholarship with Letters of C.S. Lewis, an early collection of his brother’s correspondence.

King is the first person to write a full-length biography of Warnie: Inkling, Soldier, and Brother: A Life of Warren Hamilton Lewis won the Bronze Independent Publisher Book of the Year Award in 2023. He was kind enough to give many thoughts on Warnie, both as an Inkling and as a writer in his own right.

Interview Questions

2023 was a good year for fans of Warren “Warnie” Hamilton Lewis: we got your book and Diana Pavlac Glyer’s book The Major and the Missionary: Warren Hamilton Lewis and Blanche Biggs. Were you aware the letter collection was coming out?

Yes. Diana and I have been friends since the 1980s and have often consulted one another on various projects. I started working on the Warnie biography in 2015. Diana had come across the correspondence between Warnie and Biggs in 1998 while doing research at the Marion E. Wade Center. I’m not sure when she decided to publish their correspondence, but I think it was also around 2015.

Any particularly surprising research discoveries as you were working on the Warnie biography?

Many! Some things I discovered I can only note here:

- Warnie’s boating on the canals near Oxford in his beloved Bosphorous (he published eight essays on these trips in the Motor Boat and Yachting magazine).

- The critical role he played in caring for Joy Davidman after her bone cancer was discovered. As much as Warnie had come to despise Mrs. Moore, it is important to note how much he loved Joy—as a confidante, counselor, collaborator, sister, and beloved friend. After his mother, Joy was the woman he most loved in his life. And because of Joy’s knowledge of French, she helped edit several of his books on seventeenth-century French history.

- Throughout his life Warnie took a pragmatic and hands-on view of life; he was concerned with “how things work.” The continuous flow of life, the day-to-day, and the present and pressing matters of the moment captured his attention.

- Warnie was an excellent character sketcher, revealing a sharp eye for physical description, but perhaps even more telling were his astute evaluations of the essential moral, spiritual, and social qualities of the individual under review.

- The great joy Warnie and Jack realized during their walking tours in the 1930s.

What were the more detailed discoveries about Warnie that fascinated you?

First, I was captivated by his WWI service. His experience in history’s greatest bloodbath mirrored that of thousands of others. In addition, his nightmarish days in northern France call to mind the war poetry of Edmund Blunden, Ivor Gurney, David Jones, Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Edward Thomas as well as the prose of Sassoon and Robert Graves and their German counterparts Ernest Jünger and Erich Maria Remarque.

Moreover, as a career army officer later serving in Sierra Leone and Shanghai, Warnie’s Eurocentric sensibilities made him incapable of seeing the ways in which British colonialism shaped and hampered his understanding of the native African and Chinese people among which he lived. Retiring from the army at the relatively young age of thirty-seven, Warnie spent the remainder of his life resolved to begin what he called “the business of living,” by which he meant finding satisfaction and meaning in a life outside the world of billets and barracks.

Second, I found studying Warnie’s life shed new light on his famous brother, including the warm and loving relationship between the two brothers that lasted throughout their lives. Both brothers loved each other deeply from their earliest days until Jack’s passing. Also, Warnie’s struggle with alcoholism is well known, but its origin, influence on his life, and impact on his brother’s life has not been explored in any detail.[1] Moreover, after the death of C.S. Lewis, Warnie lived another ten years—years that became increasingly dark as he grieved the passing of his beloved brother.

Third, I appreciated more deeply that Warnie was an accomplished writer and “amateur” historian—that is, he was not a university-trained and -educated scholar. Nevertheless, he researched and wrote seven books on seventeenth-century French history. In addition, Warnie collected, edited, and wrote the eleven-volume typescript manuscript, Memoirs of the Lewis Family: 1850-1930. Further, he wrote eight essays on his experiences piloting a motorboat on and around the canals in Oxford. Moreover, after Jack’s death in 1963, Warnie published the Letters of C.S. Lewis (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1966). These volumes continue to be consulted today by researchers wanting to learn more about the life of C.S. Lewis. But perhaps Warnie’s greatest written work was his diary—one he kept for roughly fifty years and running to 1.2 million words.

John Wain, himself an Inkling, had great affection for Warnie, noting among many other qualities, his penchant for excellent writing. In writing about the published portions of Warnie’s entire diary, he linked the two brothers: “I think C.S. Lewis is the best writer of expository prose that modern England has to show . . . He sets out his subject matter absolutely correctly, and his style is perfect from one sentence to the next. It’s always rhythmical, cogent, economical, memorable. The words are right, the rhythms are right. The words are in the right order, the images are right, there is no clumsy sentence anywhere. It’s absolutely superb prose.” Then he adds: “W. H. Lewis is exactly the same. In his less ambitious way, there is no clumsily written sentence anywhere in his work. He had the same gift.”[2]

Fourth, I explored in much great depth than I ever had before Warnie’s role as an original member (along with his brother and J.R.R. Tolkien) of the Oxford Inklings—that now famous group of novelists, thinkers, churchmen, poets, essayists, medical men, scholars, and friends who met regularly to drink beer and to hear written compositions read aloud and to discuss books, ideas, history, and writers. In his diaries, Warnie often wrote summaries of what occurred at the various gatherings of the Inklings. Indeed, much of what we know about meetings of the Inklings is a direct result of Warnie.

Fifth, I delved into Warnie’s participation as an active member of the household at The Kilns, the residence in Headington that he co-owned with his brother and Mrs. Janie Moore. In fact, after his retirement from the army in the early 1930s, two rooms were added to The Kilns that served as his study and bedroom for the rest of his life. I draw extensively from Warnie’s published and unpublished diaries and discover new insights about life at The Kilns, especially the relationship between Jack and Mrs. Moore; between Warnie and Jack; between Warnie and Mrs. Moore; and between the various other members of the household.

Of special interest to many will be the unhappy nature of Warnie’s relationship with Mrs. Moore. By the time of her death in the early 1950s, Warnie disliked her deeply. I spend a great deal of time in the biography documenting how completely Warnie came to despise Mrs. Moore.

Can you give us more detail on the Mrs. Moore situation?

Here’s my summary of Warnie, Jack, and Mrs. Moore:

Although Warnie says it was a crushing misfortune that his brother ever met Moore, I think it was also a crushing misfortune for Warnie since most of his life after WWI—and particularly after his retirement from the army—was blighted by his years of living with her at The Kilns. Within only a few years of moving to The Kilns, Warnie was profoundly unhappy; his relationship with Moore poisoned his life, making every night at The Kilns like marching into an unwelcoming army billet. While it would be unfair to blame Moore for Warnie’s slide into alcoholism, it must be said that his feelings towards her certainly led him to drink excessively at times as a way of coping with being around her. Second, at the center of the conflict between Warnie and Moore was Jack. Both wanted the lion’s share of his attention, and so they were jealous of each other. Moore replaced her son, Paddy, lost in WWI, with Jack; she became possessive and obsessive about him, and she fought against anything or anyone that threatened their relationship. Warnie longed to return to the idyllic days when he and Jack were in the little attic room at their home in Belfast; he resented Moore’s hold over Jack, finding it mysterious, bizarre, and pathological. If two people ever fought each other over the soul of a third, it was Moore and Warnie. Finally, both Moore and Warnie were emotionally dependent persons. Both needed someone to serve as a beacon, to be the focus of their lives—lives that sought to find meaning and purpose in what was often an existence marked by uncertainty, confusion, and heartache. Warnie and Moore would never have known each other, much less lived together for over twenty years, had not both loved Jack so much.

Inkling, Soldier, and Brother: A Life of Warren Hamilton Lewis is available where books are sold. Many of King’s essays on the Inklings have been collected in Plain to the Inward Eye: Selected Essays on C.S. Lewis. More information about his work and courses can be found at Montreat College’s website.

Come back next week when Don W. King talks about two women who played a central role in C.S. Lewis’ life: Ruth Pitter and Joy Davidman.

[1] Interviewer Note: See the F&F interview with Diana Pavlac Glyer for more insights on this area.

[2] Interviewer’s Note: See C.S. Lewis and His Circle: Essays and Memoirs from the C.S. Lewis Society (Roger White, Brendan N. Wolfe, and Judith Wolfe) p.228 for the full quote.