BY G. CONNOR SALTER

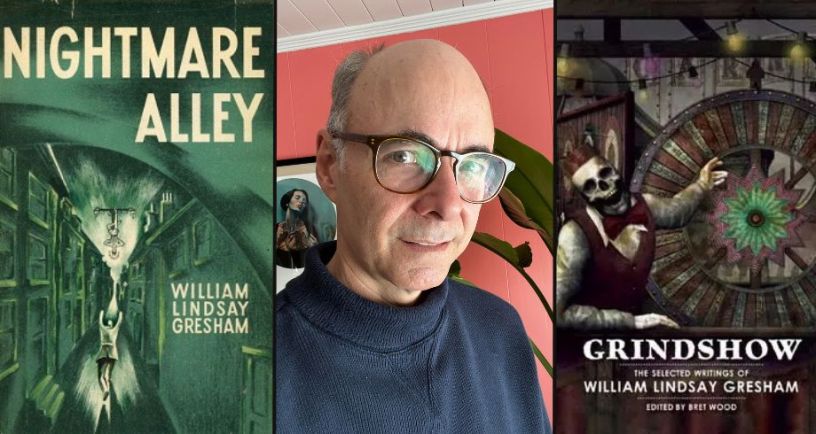

While William Lindsay Gresham is famous for helping put the word “geek” into popular American culture with his 1946 hardboiled novel Nightmare Alley, very little information is known about his life.

Filmmaker and author Bret Wood is at the forefront of efforts to make Gresham better known. In this second section of our interview, Wood discusses his seminal book Grindshow: The Selected Works of William Lindsay Gresham, his introduction to the Centipede Press edition of Nightmare Alley, and his hopes for future research on Gresham.

Interview Questions

There are some great insights in Grindshow from conversations you had with his widow, Renée. How and when did you connect with her?

That whole adventure owes its origin to Nick Tosches (Hellfire: The Jerry Lewis Story, Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams, Country: The Twisted Roots Of Rock ‘n’ Roll), with whom I’d corresponded on various weird pop culture topics since at least 1994.

I was a huge fan of his work: his depth of research; his sly, diabolical voice as a writer; his scalding wit. And that’s just what he was like as a person, so I was always kind of starstruck by him. You wouldn’t know it from his writing but he was a kind of gracious person. He was always very generous with his time and knowledge, but by the same token, he wasn’t shy about asking a favor. And that usually involved performing some labyrinthine genealogical research that could only be done on-site in Georgia (before such documents became searchable online). A mutual interest in Nightmare Alley was an early topic of conversation between us.

Around 1996, Nick came from New York to Atlanta where I was living, to research the life of minstrel performer Emmett Miller (Where Dead Voices Gather, 2001). He and I took a road trip to Macon to search for Miller’s grave and seek out the last relative who had any real recollection of the man.

A few years later, Nick suggested I make a road trip of my own to interview Renée. If memory serves, he had learned of her whereabouts from Charles Schlessiger (of Brandt and Hochman Literary Agents, who still represent Gresham’s work). Eager to emulate and please my literary idol, I agreed. I asked Charles to help me set it up.

This was fairly early in my interest in Gresham, and I regret that I didn’t already have a better knowledge of the complexity of relationships between himself and Renée, Davidman, Lewis, and his own sons for that matter. [1] What did I know? I gave Brian Sibley’s C.S. Lewis Through the Shadowlands a quick read, and I was off! I drove to Ocala, Florida, and met with Renée on September 30, 2002.

In hindsight, I think it was better that I didn’t already know too much about Renée’s life with Bill, her relationship with Joy. Renée knew I admired her late husband’s work. My ears were open, and she took the time to explain it to me. She wasn’t interested in weighing in on a literary debate, she just wanted to try and share her side of a complicated and at times tragic family story.

She used my visit as an opportunity to go through a few boxes of Gresham’s things, which hadn’t been unpacked in decades. We found a glass inhaler that was presumably used by Gresham to treat asthma, an expired driver’s license, his I Ching sticks kept in a cloth drawstring pouch. Before I’d arrived, she had set aside the note Gresham had left for her when he went to New York that day in 1962, not for a doctor’s appointment, as he had told her, but in order to pay one last visit to the magician’s table at the Dixie Hotel, then check into a room and swallow a lethal dose of sleeping pills. This was one of the first things she shared with me. She was determined to be very forthright.

Renée spoke very candidly about the time she was residing with Bill and Joy, just before Joy went to England to meet C.S. Lewis. At the time I had very little knowledge of the complexities of these triangles, and simply allowed my tape recorder to run. Going back and re-reading the transcript in preparation for this interview, I was amazed at the depth of personal information she had shared with me (which I didn’t fully appreciate at the time).

One of the first things she showed me was the typewritten note Gresham had left her when he went to New York to end his life. Clearly, she was eager to share her side of the Gresham/Davidman/Lewis story, since at that time her late husband was always being depicted as the villain, and she welcomed the opportunity to set the record straight.

She died three years later (in 2005) and to my knowledge there are no other long-form interviews with her.[2]

Returning full circle to Nick Tosches. He went on to write the introduction to the New York Review Books edition of Nightmare Alley (2010). Gresham was one of those subjects that Nick was fascinated by, and up until his death in 2019, he continued to correspond with a handful of Gresham enthusiasts, chasing some factual detail, birth certificate, or hard-to-find essay.

What were some of surprises from your conversations with Renée?

She showed me the filing cabinet in which Gresham saved his work. Typed manuscripts neatly organized. Contributor’s copies of magazines. Held in that cabinet was the definitive Gresham bibliography that so many of us were trying to compile. Even more tantalizing, she showed me the contents page of one of the 1960s men’s magazines. Gresham had notated the stories he had written pseudonymously. It wasn’t unusual for him to have three pieces in the same issue, but under different pen names. I have often wracked my memory trying to remember the different names. But I’m glad to know that the materials are safely preserved at Wheaton College, so someone can still retrieve this valuable information and contribute more pieces to the Gresham oeuvre.

What led you to work with Centipede Press on Grindshow and a Nightmare Alley special edition?

I can’t remember how I first heard about the project, but there were several of us (Bramlett and Tosches included) who were trying to track down copies of Nightmare Alley in its various incarnations, so Centipede could reproduce original illustrations. At the time it was going to be Nightmare Alley, supplemented with a selection of Gresham’s carnival essays.

I wrote to Centipede editor Jerad Walters and made a case that there was enough material to easily fill two volumes. This led to the 2013 publication of Grindshow (a term for a carnival performance that operates continuously, its endless audience brought in by the sounds of a loud bally[3] outside). Nightmare Alley included five examples of his carnival-themed non-fiction, and the introduction was focused on Gresham’s spiritual quests. Grindshow gathered 24 essays and short stories that reveal Gresham’s explorations of science fiction, crime, biography, and magic, but that merely only scratches the surfaces of the hundreds of pieces he wrote over the course of his life.

The argument was, this will likely be the only time Gresham’s work is ever anthologized, so let’s be ambitious and pay proper tribute to his work. I volunteered to write the introductions for the two volumes, and was surprised when Jerad agreed. As a writer, this is the work I’m most proud of having published, because I’m pleased with my essays but, more importantly, I feel like I made a permanent contribution to establishing Gresham’s legacy.

But there is still much more to discover. When we were putting the Centipede books to bed, I figured out that Gresham had pseudonymously written a whopping five-part tell-all exposé of phony mystics: “I Was a Bogus Miracle Man.” What makes this especially interesting is that it was published just as Nightmare Alley was going into print. On one hand, Gresham was bundling up and recycling the overflow of material he’d gathered on phony mystics. And by signing the essays “Jefferson Hall” and publishing them in Master Detective magazine (June-October, 1946), perhaps Gresham hoped these true crime articles would underscore the plausibility of Nightmare Alley’s plot of criminal mentalism.

There are still Gresham essays I haven’t read, such as his three-part true crime exposé, “My Battle Against Our Deadly Dope Racket” published in American Weekly in 1941 (by Arthur La Roe, as told to William Lindsay Gresham). If I ever get to the Special Collections at Wheaton College, that’s on the top of my list of non-fiction pieces to read. But to be frank, his early true detective writing is not very inspiring, but it does reveal Gresham slipping into character as a certain kind of writer. Becoming Asa Kendall, Jefferson Hall, or Arthur La Roe allowed him to flavor his gave him license to assume a more hardboiled demeanor or be a bit more reckless with the facts.

You write in the introduction to Grindshow about how Gresham’s an unusual hardboiled writer, often looking to expand beyond the form. Granting that he’s atypical for the genre, who are some hardboiled authors he reminds you of?

Gresham most reminds me of Horace McCoy. Their lives parallel in several ways. In his early years, McCoy eked out a living being paid by-the-word to write for pulp fiction magazines (Black Mask, mostly), but he had higher literary aspirations. One evening he goes to a dance marathon and sees in this gruesome spectacle a potent metaphor for America’s collapsed dreams during the Great Depression. He writes his first novel: They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Like Nightmare Alley, it is a masterpiece that bridges the gap between hardboiled noir and modern fiction. And like Nightmare Alley, it’s a book that’s so good that the author was doomed to never write another that could approach it.

McCoy is one of those writers, like Gresham, whose short works are impossible to find, because they have not been reprinted, and only exist in original copies of 1930s pulp magazines (which are very expensive to acquire). At one time, Jerad and I discussed collaborating on a volume of McCoy for Centipede Press. Perhaps that is an idea we’ll circle back to one day.

How did you connect with Perry C. Bramlett?

Bramlett was a C.S. Lewis historian who wrote such books as Touring C.S. Lewis’ Ireland and England and C.S. Lewis: Life at the Center. He later began focusing most of his attention on Gresham. Like me, he was on a quest to obtain original copies of all of Gresham’s stories, but also had compiled a significant amount of correspondence with those who knew Gresham personally. He had also delved deep into Gresham’s interest in professional magic.

I first came to know Perry through correspondence, at the time Nightmare Alley and Grindshow were being prepared for Centipede Press, circa 2012. He was consulting with Jerad about which stories to include, and I was brought into the conversation for suggestions and to help track down original illustrations for reproduction. Perry died in 2013, shortly after those books were published.

Several years passed, and I was put in touch with Perry’s widow, Joan Bramlett, by Domingo. She had been planning to donate Perry’s Gresham research to a particular library but had changed her mind, and wanted recommendations on what to do with the material. It was important to her that the boxes of notebooks and files not simply be put into storage, but made accessible to other researchers. I ended up acquiring the materials from Joan myself, and am now trying to determine how best to preserve and share the information. Perry preferred paper files over digital, and so the most vital documents are contained within about a dozen three-ring binders of paper notes. My dream is to have everything digitized and searchable, because right now it is a bit of a nightmare trying to locate a specific piece of correspondence in this data haystack.

When Perry died, he intended to write a Gresham biography, but was still in the process of assembling and sorting information. He had some ideas for titles and had broken down the book into chapters, sub-headings, and appendices. But other than a draft of a chapter on Limbo Tower, he hadn’t really begun writing the book. But within the boxes and bins of documents rest the raw materials for an amazing book on Gresham.

Obviously, there is a lot that has not been published about Gresham yet—no biography, no letter collection, etc. Granting that, what are some things you would especially like to see more research into?

Sheldon has written an extraordinarily well-researched account of Gresham’s life.[4] And I hope to somehow facilitate its publication.

Beyond that, I would love to see (and contribute to) an accurate bibliography of Gresham’s work, including all the pseudonymous writing, with annotations or commentary that connect these stories to Gresham’s life. Renée Gresham once told me, “The only way you’d find him is through his stories.” And by that she meant that he put all his ideas and knowledge into his work, rather than journals or autobiographical essays.

Her favorite story was “The Game Room” and she told me it was written, “when we were first falling in love, if you want to put it that way. It’s about a man and woman, in a sleazy apartment, playing a game of ‘Let’s make believe we’re in Hawaii’…game-playing about going different places, and it wasn’t at all like the truth of where they were living. In essence that’s about the most of us. And to me was a very touching story. But y’know, every experience was fodder for stories.” The story becomes richer in meaning when one knows the circumstances under which it was written.

Similarly, some of his short stories are written in the first-person, and the storyteller often editorializes with details from his own ancestry or childhood. Whether these are Gresham’s own truths or else semi-truths filtered through the voice of the narrator, they represent observations and life lessons that were meaningful to him, and define the character of the author, perhaps more so than the factual data of his life.

A great example is the 1947 short story “Tearing Out the Wilderness,” which relates a bit of family legend, of Gresham’s two-fisted, hard-drinking great uncle, “Asa Kimball.” In this story, a Civil War veteran, wracked by guilt over the death of his comrades, unburdens himself of his secret shame after falling in love with a young school teacher. It reveals a lot about Gresham’s ideas of heroism, shame, and alcoholism (he would join Alcoholics Anonymous around 1948). So meaningful was this family legend to Bill that he adopted “Asa Kendall” as one of his pseudonyms, and it was under this name that he booked the hotel room in which he ended his life.

One of the biggest misconceptions about Gresham is that he was a hardboiled crime writer. He wrote very little detective fiction. He was really more of a folklorist, and loved to resurrect larger-than-life heroes and villains. One of the last projects he pitched as a book (in 1960) was Nothing But Guts, an anthology of portraits of infamous but courageous individuals from history: pirate Henry Morgan, Pancho Villa (“bloodthirsty bandit-politico of Mexico”), gangster “Mad Dog” Vincent Coll, and others. These profiles had been written for various men’s magazines in the 1950s, and this neglected body of work represents some of Gresham’s most passionate interests.

Early in his career in the 1930s, Gresham sang folk ballads in Greenwich Village cafés. Later in life, with a little persuasion, he would take up his guitar and entertain dinner party guests with some of his songs. Renée had an audiocassette of Gresham singing his songs, but when I visited her, neither of us had a tape player on which to play it. I hope the tape survives and will be digitized as an important piece of the Gresham mosaic.

Anything new work on Gresham you’re working on?

I’m passionate about Gresham but never felt like I had the breadth of knowledge (and mental bandwidth) to write the definitive biography. But after the deaths of Bramlett and Tosches, I realized I need to be more supportive of other writers who are researching Gresham and those whose lives intersected with his. So, I am providing feedback to Sheldon on his incredibly detailed Gresham bio, and maybe in some way I can facilitate and contribute to its publication.

I also hope to catalogue the materials in such a way that they are searchable, and can serve as a bedrock of raw data as other writers continue to discover and explore Gresham’s career.

On the more personal side, do you have any upcoming projects you can talk about?

I’ve been working on a story about the notorious historical figure Gilles de Rais, but couldn’t tell you if it is going to end up being a novel, audio drama, or something else. Unlike Gresham, I support myself with a day job so I don’t have the pressures of finding a publisher, meeting a deadline, or receiving a paycheck. So, I’ll try to take pleasure in the process of writing and let that be its own reward.

(Article first published November 22, 2024).

Footnotes

[1] To summarize, Rodriguez was Davidman’s cousin, staying with the Greshams in New York to hide with her two children from an abusive husband. During her 1953 trip to England, Gresham sent Davidman a letter that he had fallen in love with Renée.

[2] Jonathan Brielle had several conversations with Renee in 1992 about adapting Nightmare Alley into a musical but did not record their discussion. For details from their talk, see G. Connor Salter, “Nightmare Alley the Musical: Interview with Jonathan Brielle.” Fellowship & Fairydust, July 18, 2024.

[3] The bally platform is the platform an announcer, or barker, stands on to announce the carnival attractions and entice customers.

[4] For Sheldon’s discussion of his research and book in progress, see G. Connor Salter, “Exploring William Lindsay Gresham: Interview with Biographer Clark Sheldon.” Fellowship & Fairydust, February 28, 2024.