BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Novelist Graham Greene and filmmaker John Ford were complicated Catholics. Greene became Catholic partly to marry his wife Vivien Dayrell-Browning and partly because he became less convinced that he could argue that God didn’t exist. As various biographers note, he seemed to swing from piety to sin—a profile by Michelle Orange in The Nation listed his many contradictory traits, including “devout Catholic, lifelong adulterer.” Given Greene’s manic depression (what would now be called bipolar disorder), it’s hard to say how much Greene’s struggles were chemical, spiritual, or intellectual.

Ford was raised Catholic, and Joseph McBride quotes him saying, “I am a Catholic … but not very Catholic.” Like everything else in Ford’s life, his need to show and yet not show too much of himself makes it hard to say what he meant with this statement. As Turner Classic Movies’ podcast The Plot Thickens explored in their series Decoding John Ford, this director craved male friendship but was toughest to the male friends he cared about the most. His movie plots combined machismo with sensitivity. He went from drinking binges to strict sober periods. He made westerns with a strict teatime break every shooting day. Like Greene, Ford contained multitudes.

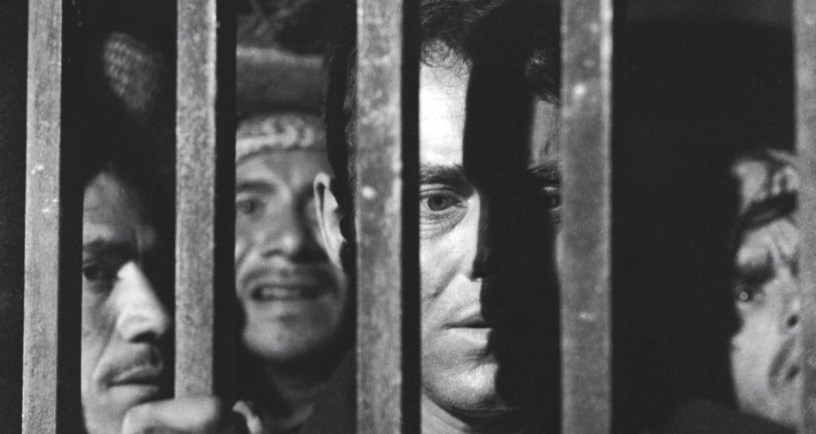

Given these complexities, it’s apt that Ford made The Fugitive, an adaptation of Greene’s novel The Labyrinthine Ways (better known today under its original British title, The Power and the Glory). Made in Mexico with Henry Fonda in the lead role, it follows a priest striving to carry out his duties in a strict secular Mexican state, always one step ahead of soldiers seeking to kill him.

Many film critics today agree that Ford is one of the most important film directors in the genre’s history. Many of his films are canonized classics. Yet The Fugitive isn’t very well known.

For one thing, it doesn’t fit well with the popular image of Ford. For better or worse, history has remembered him best for movies he made starring John Wayne—westerns like The Searchers and occasional comedies like The Quiet Man. Since Westerns and adventure films are often seen as more conservative genres, Ford is better remembered today for his late-life conservatism than for his New Deal Democrat period when he made pro-underdog dramas like The Grapes of Wrath. Stylistically and politically, The Fugitive is far from the Ford westerns your father used to watch on cable. As Bret Wood says, it belongs to “the earlier, lesser known faction of his work, self-consciously ‘arty’ films that demonstrated his interests in German expressionism, English literature and religious ideology.”

For another, Ford doesn’t follow Greene’s material too closely. Evidently, Ford decided not to follow Dudley Nichols’ script much when he began shooting in Mexico. The result looks very good. The camera beautifully mixes hard light and overwhelming shadows—a style developed in German films like Nosferatu, later applied to film noir to create claustrophobic intensity on a budget. Visually speaking, The Fugitive is one of Ford’s most beautiful films.

It’s especially a beautiful film to watch when you compare it to similar black-and-white movies that adapt similar material. I’m not sure if Greene was thinking of Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness when he wrote The Power and the Glory, although it’s plausible. By one account, Greene felt “as if there was a kind of ‘blank’ in the whole of contemporary literature” when Conrad passed away. Conrad’s flamboyant Russian and Greene’s fast-talking Mexican peasant feel like distant cousins, and there is a similar brooding existentialism as the whiskey priest and Marlowe inch their way through their respective jungles. Given these similarities, one could compare The Fugitive to the Playhouse 90 adaptation of Heart of Darkness from 1958. The TV show tries so hard to tell Conrad’s story on a small scale and falls under its poor execution and pretentious plot additions. Here, we get a similar approach—black and white film, smallish scale, a brave attempt to play with the source and still say something interesting—but it works much better.

As beautiful as The Fugitive looks, it is surprising how much of the plot has been omitted. In the novel, the priest has two marks against him: he drinks too much (his nickname is “the whiskey priest”) and has an illegitimate daughter. In Ford’s film, the priest avoids drinking (he tosses brandy over a porch in one scene), and the villager Maria has a daughter from a different man (the angry atheist soldier hunting down priests).

Fans may find the plot abridgment irritating. As John Updike observed in his introduction to the Penguin edition of The Power and the Glory, one of the book’s central themes is that a priest’s failings don’t change his office. He is called to give the sacraments and hear confession. The fact he is a flawed vessel is secondary.

So why adapt The Power and the Glory if the movie won’t include one of the book’s most interesting ideas?

Initially, one may wonder if Ford’s Catholic faith made him feel guilty about depicting a priest who has committed a mortal sin. However, Ford has no problem poking fun at priests in The Quiet Man. Perhaps Ford knew it was harder to talk about flawed priests in a serious drama, especially if the flaws aren’t something minor like Father Peter Lonergan’s fishing obsession.

It may also be that Ford wanted to contrast two ways of living out Catholicism. Nancy Schoenberger argues in a Portland Magazine interview that Ford often presents several images of masculinity in his movies: “he was concerned with men acting heroically, thus the most macho guy was not always the most heroic.” In her view, Wayne is the macho hero in a Ford movie, but he’s usually tenderer than Victor McLagen’s macho character. Wayne doesn’t appear in The Fugitive, but Ward Bond has a substantial role as “El Gringo,” a lapsed Catholic bandit who aids the priest. So, we have the fallible but goodhearted Catholic priest… and the criminal who isn’t following God as well as his childhood priest would hope. Perhaps Bond is the too-macho man, while Fonda is the tenderer man that Ford wants to be. Or they represent a spectrum and Ford sees himself in the middle.

Maybe Ford knew that he couldn’t do justice to Greene’s novel. In 1947, Hollywood movies had to follow a rigidly enforced censorship code where scripts had to be vetted before production. The rules (usually enforced by well-meaning but script Catholic censors) included barring “ridicule of the clergy.” Having an alcoholic priest with an illegitimate would certainly be considered ridicule. Many films found ways to slip sinful ideas past the censors with innuendo. But it’s one thing to do that in, say, a film noir where innuendo fills the story already, and the sinful thing instigates the main plot (a heist, a murder, a con job). It’s another to make a drama about a priest where his drinking and child become the main plot. Given the restrictions, Ford probably couldn’t have used Greene’s most interesting material even if he had followed Nichols’ script.

Whatever Ford’s motivations, he clearly understands what he wants and communicates it well. The priest may be a little more moral, but he’s still faced with dilemmas about whether he’s too selfish to be a good priest. Is he being prideful if he stays in a hostile situation where people get hurt for helping him? Does God want the priest to fulfill his office, even if others die for him? Ford doesn’t let these questions be easy, letting viewers of any denomination consider what it truly means to be a servant or a martyr.

Fonda proves especially good for the role, fulfilling what might be called the Martin Sheen Rule. Many film buffs know that Harvey Keitel was cast to play Colonel Willard in Apocalypse Now, then replaced by Sheen when Francis Ford Coppola realized he needed an actor who could be passive yet interesting. Someone whose body language meant the actor could spend most of a movie riding on a boat and audiences would stay interested. To make that material work on film, the movie needs an actor who is “easy on the eyes,” preferably someone with bright eyes and a naturally kind expression—what Sheen brings to Apocalypse Now, what Elijah Wood brings to The Lord of the Rings. Fonda has a similar assignment here—the priest doesn’t do much except travel and witness evil until the right moment comes. The fact he doesn’t have the alcoholism of the novel gives him even less to do. Yet he excels at being interesting while doing little.

The supporting cast is also well-chosen. Ward Bond proves he could play an engaging adventurer without John Wayne to help him out. Pedro Gregorio Armendáriz Hastings is suitably ruthless as the police lieutenant who hates priests, yet vulnerable enough to leave viewers wondering if his true anger is that he’s trying to stamp out his own belief in God.

Hastings is also believably tender when a plot shift requires him to recalculate. As mentioned earlier, the script makes him the illegitimate child’s father, not the priest. When he realizes he is a father and that the priest baptized his daughter, he must decide whether he can kill the man who christened his child. Every movie changes the source material—in this case, radically so. The mark of a good adaptation is if the changes serve the story well.

The Fugitive may be too simply plotted for some—more interested in great images than keeping the plot exciting every minute. It may not be the best adaptation of a Greene story—many fans will prefer Brighton Rock or The End of the Affair. However, it knows what it wants to do and does it well.

Perhaps especially today, after movies like Sorcerer or Apocalypse Now have redefined how to tell the existentialist jungle road trip story, it’s instructive to see how Ford offers another method (more expressionist, smaller-scaled, more claustrophobic). He even handles the religious material without stumbling into clichés or making it seem too simple—a hard thing in any filmmaking period.

Decades after their death, Graham Greene and John Ford are still two of their generation’s most complicated Catholic storytellers. Some ideas they raise have become more controversial today. As toxic masculinity becomes a larger and larger discussion, viewers ponder how to feel about Ford’s Westerns. As church abuse scandals affect Catholics and Protestants alike, many may question Greene’s thesis that a priest’s office matters more than his character. Do we have to choose between Jesus and John Wayne? Do we treat priests differently if they have feet of clay?

No one would call these questions easy. Perhaps what makes movies like The Fugitive so worth watching now is that they refuse to make it easy. They challenge us to keep seeking the answers in faith.

I’m working my way through all of Ford’s films right now and this is a very thoughtful review that helped me clarify some of my own impressions after seeing it. I think the issue is more the dialog than the plot. The Fugitive would have been better as a silent film, frankly, because it is amazing looking and the concepts are broad enough and plot clear enough not to need the dialog.

LikeLike