BY AVELLINA BALESTRI

I have always been sympathetic towards the British/Loyalist side of the American Revolution and had the pleasure of watching an interview where the author of this book discussed the story of her ancestor, Charles Asgill, a young British officer who was very nearly executed in a revenge hanging towards the end of the bloody conflict determining the fate of empires. Having already learned about his story through the memoirs of Sergeant Roger Lamb, which were among my favorite reads growing up, my interest was further piqued by Anne Ammundsen’s extensive research and clear passion for bringing her ancestor’s harrowing experiences to the attention of the wider public. Eventually, we became friends on social media after crossing paths on an American Revolution history group, where we were quite possibly the only Loyalist sympathizers in the room!

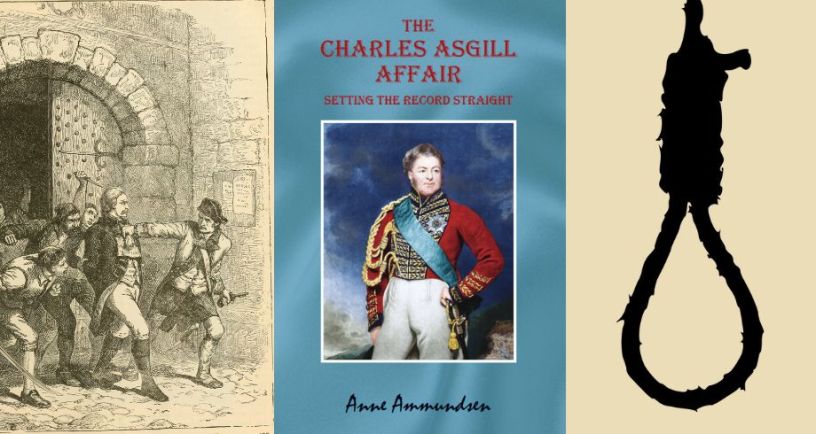

I am even more impressed by the scale of her study and dedication to this topic after receiving a copy of her book The Charles Asgill Affair: Setting the Record Straight, which also follows the titular character’s life after the war, a life he might not have lived if the forces of vengeance had their way. I particularly appreciated the letters included from Asgill and others involved in the unfolding drama that could easily have mirrored the sad fate of Major John Andre but had a much happier conclusion. It is a very underrated slice of history, subject to partisan spin-jobs as the fratricidal conflict bled out to its conclusion, with both sides striving to come away with something that resembled honor. Honor, though, was often sacrificed in the violent cycle, and the innocent were made to suffer as scapegoats for those with red hands.

While Asgill is certainly the protagonist of the piece, one of the primary heroes of the affair is the Scottish officer Major James Gordon, who was determined to save his young charge from such an ignoble and unjust fate one way or another, even if it meant sacrificing his own life if all else failed. After the “unfortunate” lot was drawn for Asgill, Gordon would not allow himself to rest, and “spurred Frenchmen and British and Americans to action,” eventually pricking their consciences on behalf of the condemned young man. It might be argued he poured his last life’s strength into saving the youth, given how soon after he died, a changed man. A memorial to this gallant officer has recently been installed at Trinity Church, NYC, where he is buried in an unmarked grave, which Anne, with good reason, considers to be one of her proudest achievements.

Lord Charles Cornwallis once remarked, in a moving testimony to his deceased fellow officer, “When I first knew Gordon, twenty years ago, gay in gay London, who could have guessed how much lay in the man?” Anne also includes a passage from General John Burgoyne commemorating the death of his comrade and confidante, General Simon Fraser, applying the sentiments as equally applicable to Gordon: “To the canvas, and to the faithful page of a more important historian, gallant friend, I consign thy memory. There may thy talents, thy manly virtues, their progress, and their period, find due distinction and long may they survive long after the frail record of my pen shall be forgotten.”

Meanwhile, in contrast to selfless and compassionate Gordon, Washington comes off as quite a flawed character, more than willing to break a few eggs to make an omelet if it suits his goals (including those centered upon revenge), then eschew responsibility when his actions are called into question or he fails to receive the type of gratitude he thinks he deserves for stepping back from the brink. Far from being unable to lie, he can very easily alter facts to frame a story the way he wants to defend both himself and the revolution. This does not blot out Washington’s more admirable qualities, but should be a sobering reminder that he was a man, warts and all, leading a hard-fought rebellion that involved both blood-letting and mud-slinging.

The bitterness of the conflict also left roughly a third of Americans as political exiles in the land of their birth. Still loyal to the line of kings given allegiance by their ancestors, they found themselves torn between trying to make peace with a new government they considered to be fundamentally illegitimate or going abroad. Either way, they were no less American than their pro-rebellion compatriots. To them, and by extension to modern-day sympathizers like me, the story of British officers such as Charles Asgill is nothing less than our heritage too.

I am of the opinion that Asgill’s near brush with the hangman’s noose would make an incredible film, and Anne Ammundsen’s book would make a wonderful groundwork source to create a screenplay around. I highly recommend it as a read for all those interested in unique characters and aspects of the period. It is a story not just of high-stakes drama, but also a testimony to the endurance of the human spirit and abiding human decency that cuts through cycles of revenge.

~

To purchase The Charles Asgill Affair: Setting the Record Straight, go here:

To watch Anne Ammundsen’s enlightening video interview, go here: https://www.family-tree.co.uk/how-to-guides/charles-asgill-setting-the-record-straightting-the-record-straight