BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Dr. Sørina Higgins (2021, Baylor University) has many interests. She has published two poetry books (The Significance of Swans and Caduceus). She hosted a podcast, 1619 & 1776, on the state of American Christianity. However, she is probably best known for her work on Charles Williams (1886-1945). A later member of the Inklings, Williams wrote in many genres, most notably supernatural thrillers, mystical dramas, lay theology, and Arthurian poetry—all imbued with an offbeat tone informed by his Anglo-Catholicism and involvement in multiple secret societies.

Higgins has contributed to several books collecting Williams’ work, including writing a preface for a 2016 edition of Williams’ poem collection Taliessin through Logres and editing the previously unpublished The Chapel of the Thorn: A Dramatic Poem.

Her academic essays have appeared in many places, including Mythlore, VII, The Journal of Inklings Studies, The T. S. Eliot Studies Annual, and International Yeats Studies.

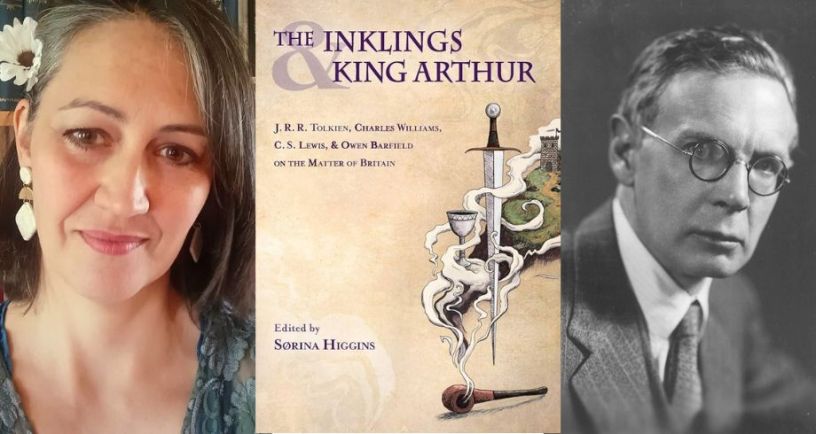

In 2018, she won the Mythopoeic Society Inklings Scholarship Award for editing The Inklings and King Arthur: J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, C.S. Lewis, and Owen Barfield on the Matter of Britain. She’s currently writing The Oddest Inkling: An Introduction to Charles Williams, slated for publication by Apocryphile Press in 2024.

She was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

You’ve said your first exposure to Williams was when someone gave you his novels. What attracted you to the novels when you first read them?

Even before someone gave me the novels, my favorite undergraduate professor kept talking about Charles Williams. He kept saying, “You should read his works because you like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.” In my obnoxious undergraduate way, I kept thinking, “Well, one, if I’ve never heard of him, he can’t be that good. And two, who’s got time for that?” But right after I graduated from undergrad, I think it was my sister who gave me two of the novels for Christmas. I read The Place of the Lion first, and like Emily Dickinson said about poetry, it lifted off the top of my head. It was an amazing experience.

What were some of the things that attracted you at first?

The brilliant, beautiful, vivid visual imagery, I think. There are pictures in that novel that are unforgettable—the gigantic platonic archetypes coming to life in the world. Then, the very strange writing style I found to be an appealing challenge. Beyond that, probably most of all, it was the way that ideas come to life in unforgettable ways in his books.

As a poet yourself, what are some things that you find interesting about Williams’ poetry?

First, I’m interested in how his poetry evolved across his lifetime. It started out very derivative, imitative, and even old-fashioned for its own time. But in the early 1930s, he edited a collection of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poetry, and his own verse greatly improved as a result. It became more alive, more concrete, with shorter, more descriptive words. His rhythms became a lot more complex and beautiful.

Again, I love when he is able to evoke a visual image in his poetry. I also like the way he works the sentence against the line to create interesting tensions and pacings throughout the poem. To put it really simply, he uses enjambment—he doesn’t end every sentence at the end of a line. Anyone who practices formal, metrical poetry knows that’s what really gives it the rhythmic interest: when the sentences and the lines have conflicting rhythms so they create a counterpoint, like in the music of Bach, for instance.

The book Inklings and King Arthur was a great success. How did that project come about?

I knew that C.S. Lewis and Charles Williams wrote a great number of Arthurian works—especially Williams. Then in 2013, Tolkien’s one explicitly Arthurian work was published posthumously: The Fall of Arthur. I knew it existed, but no one had any idea of how extensive it was. There were significant materials, very exciting, with notes and commentary by Christopher Tolkien. I read that book with great enthusiasm and realized one could create an imaginary composite Inklings Arthuriana. We could take the works by those three authors and put them together into an imaginary world and see whether and how they matched up.

So I started poking around in the works of Owen Barfield and found out he had an unpublished Arthurian piece and then a few other works with Arthurian references and analogies. I was talking about this fact with Brenton Dickieson and saying: “Someone needs to edit an anthology about this.” He said, “why not you?” So I did.

How long did it take to produce the book?

It took three years and a bit. The Fall of Arthur was published in 2013; I think I issued the call for papers that year. Then I collected and edited the articles over the next two years. It took about a year to revise, get permissions for the quotations, and make the index for the book. It came out at the very end of 2017, just a few days before 2018.

I am very grateful to all the chapter writers for their excellent pieces in that book. I think it’s a brilliant collection.

Were you surprised to win the Mythopoeic Award?

That was a very pleasant surprise! It’s an excellent award, and there were many other good books nominated that year. So, yes, I was surprised and pleased. But that award goes to every one of the authors of the chapters.

I know you write fiction as well. Do you see any Inklings influence there, or is it more background?

There’s less than I myself would expect. The fiction I’ve written that remains thankfully unpublished—a murder mystery and a quasi-realist, quasi-dystopian novel—bears almost no superficial resemblance at all. But the influence definitely is there.

One thing I admire in the works of C.S. Lewis to which I aspire is clear syntax: streamlined, straightforward sentences. What I love in Williams, as I said, are the visual descriptions and the sense that there are huge theological ideas underlying the work. An analogy would be the historical and linguistic work that underlies Tolkien’s writings; but in Williams’ case, it’s church history and theological concepts. So, perhaps those are influences.

One short story of mine is directly inspired by Williams. The title is “Incoherence,” and it’s essentially the tale of a young man who rejects Coinherence, who rejects mercy, grace, and community. That’s a direct influence.

The others are much more subtle. I have a story that is a myth retold. I had Till We Have Faces in the back of my mind—how do we tell all of the human story of the main character in a myth who’s left out of the Greek versions that we’re familiar with?

Since you mentioned Coinherence, we should probably clarify. What is Coinherence, in Williams’ theology?

Coinherence is his idea that, put simply, we are all members of each other and everything that we do influences everyone else. It’s a more theological version, perhaps, of the Butterfly Effect or the idea that we are a global village. But it’s grounded in the persons of the Trinity: That the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are in “perichoresis” with each other, which is a communal dance, an intermingling, the three persons dancing together.

That’s the concept of coinherence—that we are in some literal, theological way, members of one another. The slightly weirder doctrine based on it is Williams’ signature idea of the Way of Exchange or Substitution. That’s based on coinherence: because we coinhere in each other, he believed we can make verbal contracts with one another to carry our intangible burdens. If, say, you and I were walking out of a building with luggage and boxes, we could carry those for each other. It would be very easy. He believed we could do the exact same thing with one another’s illness, grief, sorrow, mental burdens, etc. He established an Order to practice this, where he would assign his disciples to carry each other’s non-physical burdens.

I believe this leads into the story of C.S. Lewis and Joy Davidman—Lewis pondering whether he took on Joy’s illness when she recovered from cancer.

HIGGINS: That’s right. She had agonizing pain because the cancer had eaten away her femur, and he prayed that he could take the pain. Surprisingly, he got a terrible pain in his bones—he developed osteoporosis, which is the leaching out of calcium from one’s bones. Her bones regrew the doctors said it was a miracle. Lewis then wrote to a friend, “One dreams of a Charles Williams substitution!”1

Researching Williams’ occult interests has required you to dig into some strange topics—your doctoral dissertation focused on how he and contemporaries like Aleister Crowley and William Butler Yeats were simultaneously involved in ceremonial magic and drama, that fusion’s impact on their writing. Was there a point in the Williams research journey where you realized, “I’m getting into strange territory,” and had to commit to taking the research journey, or was it a more gradual realization?

There were two very clear moments.

The first was the most difficult for me as a young woman and as a Christian. I read the novels, I read the poetry, I read some literary criticism. Then I read Letters to Lalage, a series of letters from Williams to a young woman named Lois Lang-Sims. In the book, she reveals how he carried on a very intense relationship with her that involved ceremonial practices that she didn’t quite understand and that she was uncomfortable with. When she asked him to stop these practices, he immediately cut off their friendship altogether. She experienced a great deal of psychological hurt and confusion. At one point in their relationship, she was bedridden for six weeks with intense physical and mental weakness, as a result of the emotional manipulation that he put her through. This was horrifying to me. I had thought of Charles Wiliams as a Christian mentor through his books—some of his books have beautiful inspirational scenes and concepts about sacrificial love. So, to find out he had mistreated someone so severely was extremely difficult.

That was the first moment, and I had to decide whether or not to keep studying his works. But I did, because I figured his theories and his theology were better than he was as an individual—and that is always the case. That is always the case with any theologian or Christian master.

The second moment was when Grevel Lindop’s biography came out, and there Lindop reveals further details about a second secret society that Williams was in that no one knew about previously. The one that we did know about was a Christian mystical society, the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross. The second one, an offshoot of the Order of the Golden Dawn, practiced rituals that are more troubling—again, to me as a twenty-first-century female scholar. They involved transmutation of sexual desires, and seemed to be quite troubling, especially given that he sometimes practiced these in what we would think of as situations that did not involve informed consent. But at that point, I had crossed over to studying his work academically rather than just for personal pleasure, so I was already committed to the research journey. This goes on. I continue to wrestle with his personal failings while appreciating the literary quality of his writing.

You have talked on your blog about some of these issues. Williams could be a wise spiritual mentor, and he could be controlling. He apparently didn’t consummate any extramarital relationships, but he did lots of “spiritual exercises” with women that had sadistic, quasi-sexual overtones. Have you been able to reconcile or compartmentalize it, is the wrestling ongoingt?

I keep wrestling with it. I’ve been unable to reconcile or compartmentalize it. You’re right that he didn’t have a fully consummated extramarital affair, but he absolutely had an affair with one woman, Phyllis Jones, for years. It was an intensely emotional affair; she reciprocated at first and then withdrew her affection. It was also a sexualized relationship if not consummated.

He was practicing an ancient technique of taking intense emotional experiences and transferring that energy into either creative acts—writing poetry—or into spiritual devotion. This is a technique that many traditions have practiced throughout time, just not in evangelical or many types of Christian circles. It’s very questionable to a lot of us, and in his case, the problem is that it turned abusive. He did not explain it to many of these disciples or get their willing participation. Some of those women did participate in it willingly and joyfully, and others did not.

I think there are two different problems. One is the whole practice itself, that many of us are unfamiliar with and uncomfortable with. The other is if it was done to unwilling victims.

The only way I can mentally manage these problems in Williams’ lif, is to come back over and over to the idea that every one of us is horrifically broken. Every pastor, every spiritual mentor, is a terribly broken person with dark sins. I would be very hypocritical if I said Charles Williams was worse than I, or that therefore we shouldn’t study his work to draw their good qualities out of them. I think we should.

While we’re talking about Williams’ behavior, I am curious if you see any “smoking guns” in his life story. Sometimes we can see painful events that may explain where the addictive behavior started, or what pain the person was compensating for. Can we see anything in his early life that suggests where the dysfunction started?

Nothing huge and obvious. The family did struggle with poverty. His father went blind and lost his job, and then tried to start up another entrepreneurial endeavor that wasn’t very successful. Williams was sick as a child—he had childhood tuberculosis from drinking unpasteurized milk. That illness damaged his intestines permanently and is what killed him at a fairly young age. Other than that, he seems to have had a happy relationship with his parents, sister, and extended relations. I guess the real answer is No.

In the last few years, we’ve seen many Christian groups wrestling with the fact their spiritual leaders weren’t who they seemed to be. Has looking at Williams’ complexities given you any insights into how we can navigate those waters?

I wish it helped me, because I have experienced that myself. I was a member of a church that I loved, I was happier than I have ever been in any other church. Then when COVID came, it exposed some of the leadership’s dark sides.

I would say “No,” until recently. Your article for the Oddest Inkling about ways Williams’ life parallels some behavior we’ve seen in toxic church leaders like Mark Driscoll and Bill Hybels was very helpful.

One thing that may be helpful but sad is simply that this happens. You give people power, and they will misuse their power. In Christian circles, we have a history of giving power to men of a certain age, economic status, race, etc., and then we put them in positions of power over women, children, working-class people, minorities in their congregations, and then we’re surprised that they abuse their power.

That leads into an interesting point. Recently, we were discussing the fact that Williams came from a working-class background, where material success or influence were hard to achieve. You observed that secret societies like the Fellowship of the Rosy Cross were very popular with people who fit that profile, or were otherwise marginalized.

Exactly. Occult groups were really popular in England from the 1890s to the 1920s and a little beyond. I think one reason they were so popular is they welcomed in and gave power to people who couldn’t have power out in mainstream institutions.

Women could not become priests in Anglican or Roman-Catholic churches, but they could become priestesses. Women could not receive degrees from Oxford until 1920, but they could rise up the ranks in these occult orders all the way to the top and become the highest ranking leaders. It was a woman, Florence Farr, who eventually took over the Order of the Golden Dawn in England and kicked out the founding leader.

So these orders were very popular for women and for working-class men who couldn’t afford a university education. It really was like a Bachelors/MA/PhD system: there were ten levels, and at every level, one had to pass a written examination and then perform a practical examination. Then they would receive a grade and a rank and be initiated into the next rank. People traveling up these ranks could feel educate, and empowered in very real ways. They would wield real power inside the order that would perhaps replace their sense of not having any power outside the order.

Obviously, since Williams has been under-researched, there are lots of areas that could use more exploring. What are a couple of areas you would particularly like to see more research being done?

When I was at Wheaton College’s Marion E. Wade Center in October 2023, I discovered an enormous amount of unpublished material. I’m currently talking to other scholars to figure out what this material is and how it relates to published material—is it just drafts or discarded, or is it whole new material?

There’s a lot more that I didn’t even touch during my trip. One area is we just need everything published. There are plays, there’s a novel fragment, some essays and talks and things that have never been published. First, get it all out there.

A couple of others I’d particularly like to see more work being done:

The relationship between Williams and his mainstream modernist contemporaries. More work on him and William Butler Yeats, him and T.S. Eliot. There are some younger modernists that Lindop mentions in the biography—Kingsley Amis, and Philip Larkin, and a few others of that generation.

I’m trying to do more work on Williams’ plays and poetry. We have a Collected Plays, but it’s by no means all of them. We need a Complete Plays volume, probably annotated. I’m working on the annotated Arthurian Poetry, which I could use help with if anyone’s interested.

Outside the Inklings, who are some authors who get you excited?

All of them. Whoever I’m reading at the moment. The ones that I study are Yeats and Eliot—T.S. Eliot that is, not George. But honestly, whoever I’m reading right now—and that happens to be the contemporary Chinese science fiction authors Ted Chiang and Liu Cixin.

You balance many skill sets: fiction, literary research, poetry, and editing. What are some things that help you balance all those elements without overworking yourself?

Yoga, sleep. I tend to work mainly on just one or two at a time. I have not written poetry since before I started my PhD. Actually, I don’t think I have written poetry since I got a smartphone, and I think the two are not unrelated. I do tend to write in seasons, with whatever genre is foremost.

What are some future projects you can tell us about?

Oh, so many. The main one right now is a book titled The Oddest Inkling: An Introduction to Charles Williams. I hope to have that finished in several months and published in 2024. That will be a popular-level guide, welcoming new readers to his work and giving them some tools for developing discernment when they come across disturbing material.

The one after that is the annotated Arthuriad—all of his Arthurian poetry, with a couple of collaborators.

I am also working on revising my dissertation into a book that I hope will soon be accepted by a publisher. That is called From Thaumaturgy to Dramaturgy: Staging Occult Modernism.

I currently have a volume of short stories under consideration by a publisher.

I know you also recently became part of an editing service, Wyrdhoard. What can you tell us about that?

HIGGINS: Yes! In addition to my own writing, I’m a member of Wyrdhoard, a consultancy of four freelancers available for hire. Between us, we can help writers with any stage of the writing, revising, publishing, and marketing process from the very beginning to the very end. We can brainstorm, beta read, copy edit, proofread. We have someone who’s an expert in marketing and social media. We have someone who can do the formatting. We also have translators on the team. If someone wants to self-publish, we can take them all the way through that process.

In addition to being an author, I have a passion for helping other authors to perfect and polish their works and get them out into the world.

More details about Sørina Higgins can be found on her BuyMeACoffee page and her website. More information about her editing services can be found at Wyrdhoard.com.

Footnotes

- See Lewis’ November 1957 letter to Sheldon Vanuaken in Collected Letters Volume 3, pg. 901. For more details on Lewis’ view of Coinherence, read Andrew C. Stout’s Mythlore 35.1 essay “‘It Was Allowed to One’ : C.S. Lewis on the Practice of Substitution.” ↩︎