BY G. CONNOR SALTER

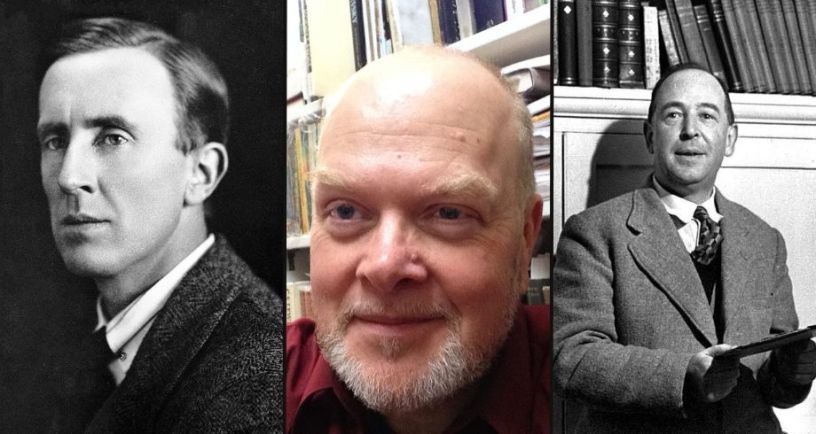

The first section of this interview with Dale J. Nelson (professor emeritus of Mayville State University) focused on his work exploring weird/horror fiction. While he has contributed some fascinating works in that area, particularly his thoughts on Arthur Machen (see his articles for Darkly Bright Press) and H.P. Lovecraft (see his article in Mallorn), he is also a prolific Inklings scholar. He writes regular columns for Beyond Bree and CSL: The Bulletin of the New York C.S. Lewis Society, and has contributed to books like the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia edited by Michael Drout (Routledge, 2006).

Here, he discusses how he became interested in the Inklings and areas he would like to see new scholars explore.

Interview Questions:

How did you first become interested in the Inklings?

First, thanks for this opportunity to talk about these favorite authors.

As near as I can tell, I first read Tolkien at age 11 in late 1966. From the first half of 1967, I have documentary evidence of having read Tolkien, in the form of surviving home-made comic books that show his unmistakable influence, such as my naming one of my characters Drogo.

I seem to remember the day of my first encounter with Tolkien. During the “Hobbit Craze,” newspapers and magazines reported on Tolkien as a campus fad. The Coos Bay, Oregon, public library set up a display in the adult fiction section with the Ballantine paperbacks and a poster, probably the Middle-earth map drawn by Barbara Remington. She had illustrated the book covers with a colorful, continuous semi-abstract design. This art looked sort of science-fictiony to me and so I looked the books over. I checked out The Hobbit. It was as if the book had been written specifically for me.

The Hobbit and then The Lord of the Rings were books about long walks, and I was a sturdy walker around the hills and byways of that woodsy lumber shipping port. Without doubt, coming under the spell of Tolkien was interwoven with my developing enjoyment of winding trails in the ferny woods. If I might digress from the Inklings for a moment—a little-known book I discovered in the children’s library also contributed to the fostering of an imaginative attention to nature. This was outdoorsman Denys Watkins-Pitchford’s copiously illustrated tale The Little Grey Men. And Barbara Ninde Byfield’s amusing book The Glass Harmonica: A Lexicon of the Fantastical also pleased me. She wrote the text and drew the pictures. She included a drawing of Gandalf and the Balrog at the Bridge of Khazad-Dûm—though there were no explicit Tolkienian references in the text.

For several years, it seems I read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings annually. By the end of 1973, I had finished a fifth reading. Along with those books I read the contents of Ballantine’s The Tolkien Reader, which included not only the Bombadil poems and Farmer Giles of Ham, but Tolkien’s scholarly essay “On Fairy-Stories.” What I made of that on a first reading, I don’t know, but after all it was by Tolkien! Since I ended up majoring in English, this first taste of academic prose was a landmark on my career’s journey.

Sometime when I was around 12, I discovered the Chronicles of Narnia in the children’s section of the library, and I liked them well.

William Ready’s The Tolkien Relation, paperbacked as Understanding Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings, appeared in early 1969 and I got hold of a copy. It was a shoddy piece of work, but it was about Tolkien and so it interested me. Who knew, Tolkien’s mother was a missionary “among the women of the Sultan of Zanzibar” (6)! … I was a naïve reader.

Ready cited various books and magazines and used the abbreviation “Ibid.” To me, Ibid appeared to be the name of a periodical that had printed biographical material about Tolkien, and I went looking for back issues in the library’s magazine stacks, without success.

Ready mentions both Lewis and Williams, but a better book, Lin Carter’s Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings, released March 1969, was a lot more fun to read and more useful about Tolkien’s friends and precursors. Carter refers to Williams’s “several fine novels on occult and mystical subjects” (p. 16).

At any rate, before I turned 14 in mid-1969, I had read of “the Inklings,” and Tolkien and Lewis were established favorite authors. I must have read Out of the Silent Planet before that 14th birthday.

It seems that I read That Hideous Strength during the 1969-1970 junior high school year, that is, 9th grade. My memory is that I was so fascinated by the Latin exchange between Ransom and the resuscitated Merlin that I told my English teacher, Mr. Paulsen, that I wished the school offered Latin. “Why? It’s a dead language,” he replied. Uff da!

It seems Perelandra had to wait to be read last of the books in the Ransom trilogy.

I didn’t read Williams till high school days, having found Many Dimensions on the city library shelves. I didn’t get into Williams till college days. One of my Southern Oregon State College professors, Brian Bond, turned out to be an Inklings reader who had published an essay in Mythlore.[1] As well as offering courses in fantasy (with Tolkien, Lewis, and Williams), he consented to an independent study on Williams’s Arthurian poetry. By then I was 20. So from the threshold of adolescence to the threshold of the voting age, I was growing with the Inklings. (It wasn’t till I was a high school English teacher that I first read Owen Barfield. Eventually, we corresponded a little before he died.

By around 1974 I found myself ready and eager for Lewis’s splendid books of apologetics. He helped me not so much with doubts, which didn’t much trouble me, but by wonderfully expanding my sense of Christian heritage and doctrine, and with Christian life as contrasted with the confines of the church I attended. In fall 1976 I was deep in the turmoil of first love, and writings by Lewis and Williams helped me to understand that experience.

What are some things that have kept you interested in them as a group, enough to keep returning to their work?

Lewis, Tolkien, and Williams are outstanding imaginative storytellers. I’ve read Out of the Silent Planet 16 times and The Place of the Lion five times and could pick them up again right now and read them with great pleasure. Each man’s work is of a piece and yet a pleasing variety abounds. The Screwtape Letters is different from Till We Have Faces. The Silmarillion is different from Smith of Wootton Major. War in Heaven is different from Descent into Hell. But each brings “news from the real world.” I don’t mean that in a Platonic sense, but refer to this world in which we choose, live in penitence and in faith, hope, and love (or not), this world created not by mindless chance or emanating from a mysterious, remote Mind, but this real world created by “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob”—as Pascal put it. These Inklings are sincere Christian believers. Each man embraces the Faith. And each author entertains—superbly—but moves the reader to become wiser, moves the reader variously to self-examination, to adoration of the living God, to hope.

One of the most appealing things in the writings of any of the Inklings is Lewis’s depiction of the St. Anne’s household in That Hideous Strength. It’s a place of silence and of good conversation, of gardening and husbandry, of hospitality, hierarchy, and healing. It’s Lewis’s counterpart of Tolkien’s Rivendell. In The Silmarillion, Tolkien describes Elrond’s Last Homely House thus: “a refuge for the weary and the oppressed, and a treasury of good counsel and wise lore.” Jane Studdock finds that refuge and that treasury at St. Anne’s. Every Christian household, in some degree and in a way appropriate to its unique character, should be like Rivendell and the St. Anne’s house.

So, much that keeps me interested in the Inklings is not just academic curiosity or opportunism but a concern for the moral imagination incarnated in our lives and homes; and these books are delightful to read. At the moment I’m reading The Lord of the Rings for the 14th time.

Was there a point where you shifted from being an Inklings reader to performing scholarship on them?

Year after year, I take them off the shelf and read the books, poems, and essays without necessarily planning to write about them. As for the beginnings of scholarship… I sent letters to the Mythopoeic Society’s monthly magazine Mythprint, sharing space in the letter column with people such as veteran Inklings reader Dainis Bisenieks, who became a friend many years later. Also I wrote letters to the New York C.S. Lewis Society and book reviews for my apazines (home-made magazines for amateur press associations). These were baby steps in the direction of scholarship.

I joined the Mythopoeic Society in 1974, the best time to do so. The articles then were often thoughtful but they were not addressed to a narrow professional academic audience. All these engaging, smart people digging into Tolkien, Lewis, and Williams together! “Joyful in the Great Dance” was their motto. One wanted to join in with this ongoing in-print symposium—a “symposium” more like Plato’s dinner party with good talk rather than the current sense of “symposium” as a formal academic occasion in which people embellish their CVs.

Many years later, when I studied for an English MA at the University of Illinois, one of my professors was U. Milo Kaufmann. He’d contributed an essay to A Tolkien Compass and served as a consulting editor for Mythlore, so I’d known his name for years before I met him. He granted my request for an arranged study on Inkling Owen Barfield. Barfield is like Origen, a thinker with gifts for the Christian Church who, however, must be read with discernment. Milo encouraged me as a scholar.

I’d say my first scholarly effort related to the Inklings began in 1989, when I wrote an article for North Wind, the journal of the George MacDonald Society; it was very soon followed in the NY CSL Society’s Bulletin with a long bibliographic essay, “C.S. Lewis and Weird Fiction.” Therein I wrote about Lewis’s youthful enthusiasm for Algernon Blackwood, Rider Haggard, &c, and Walter de la Mare. I committed a real blunder when I reported that Lewis had read de la Mare’s long novel Memoirs of a Midget. Alas, I have found no evidence that he even knew of the book. Given Lewis’s interest in de la Mare, he must have taken up the book, but I don’t know that he did.[2] It should be remembered, by the way, that after witnessing Dr. Askins’s spiritual torment and horrible breakdown in the mid-1920s, Lewis seems henceforth to have avoided most weird fiction!

Any subjects in Inklings studies you would especially like to see more scholars explore?

There remain topics for further research. Horobin’s recent book on Lewis’s Oxford was excellent. Bowers and Steffensen’s study of Tolkien’s 1913-1959 Chaucer scholarship should be in my hands any day now.

I would like to know more about Lewis’s brother Warren. I’m interested in the penumbra of the Inklings, too. Don W. King wrote a biography of poet Ruth Pitter and edited her letters—these were real contributions to Inklings scholarship (and beyond). What about poets Herbert Palmer, Phoebe Hesketh, Francis Warner? A.C. Harwood and Leo Baker? Tolkien’s brother, and his children other than Christopher? The Inklings’ many professional colleagues? Former pupils of Lewis and Tolkien? Douglas Anderson turns up eye-opening finds at his Tolkien and Fantasy blog. Myself, I hope to publish on Lewis’s pupil Martyn Skinner, author of The Return of Arthur and other books of poetry. I’ve been in touch with a member of the family. We’ll see.

As for methods… I’m often not very interested in current academic studies of the Inklings. Some exceptions include the writings of Shippey and Flieger on Tolkien and Ward and Schaekel on Lewis (Imagination and the Arts in C.S. Lewis).

I’m interested in social-historical contexts. I contribute to the latter subject with the ongoing Inklings Century series at Beyond Bree. David Llewellyn Dodds and Matthew Thompson-Handell are also contributing to the series. Independent scholars are diligently adding to our knowledge of the Inklings; these researchers include Seamus Hamill-Keays, Nancy Bunting, and others.

I don’t care for exercises in theory (queer theory, feminist theory, postcolonial theory, Marxism, psychoanalytic theory, etc.); my impression is that these are given to exhibitions of cleverness and even perverse misreading rather than applications of wisdom.

Oh, and I would like to read about individuals, families, communities that have been inspired by Lewis and Tolkien to take up deliberate living over against simply falling in line with what Paul Kingsnorth calls The Machine.

I’m curious since you’ve done so much work on understudied Inklings topics or how they intersect with writers they don’t immediately seem connected with. Any advice for researchers looking to underexplored areas?

Here it is: read the books they read. Get Holly Ordway’s Tolkien’s Modern Reading and review the appendix, and download the list of books in Lewis’s library. This 1969 record is available from Wheaton College in Illinois. As you read Tolkien and Lewis, make a note when one of them name-drops a book or a poem or short story. Build that list as you go along. What with Project Gutenberg, the Internet Archive, Abebooks.com, and interlibrary loan, it is often pretty easy to get hold of those works. I must have on hand something like 50 books that I haven’t written about yet, that were read by Tolkien or Lewis, or known by them, or at least in their libraries. Many of these books I have on hand are photocopies or prints from online sources. I’ve done over 60 columns on books Lewis read or that, at least, were in his library as catalogued after his death, etc., for the New York C.S. Lewis Society, plus an earlier series of articles on “Little-Known Books in Lewis’s Background.”

Let me try to stir up some enthusiasm for this kind of research. What a variety of books there is in Lewis’s background, from Laxdaela Saga to Bohun Lynch’s Menace from the Moon to the medieval romance The High History of the Holy Graal! Now The High History was a book Lewis, Williams, and Machen praised, in Sebastian Evans’s version. Lewis wrote to a friend, “It is absolute heaven: it is more mystic & eerie than [Malory’s] ‘Morte’ & has [a] more connected plot.” Towards the end of the High History we read of the castle of King Pelles’s son Joseus. He “‘slew his mother there. Never sithence hath the castle ceased of burning, and I tell you that of this castle and one other will be kindled the fire that shall burn up the world and put it to an end.’” Wow! Reading these books the Inklings read is not drudgery—you might discover some new favorites that everybody else has forgotten.

Here are four novels I own but I haven’t read and written about (unless a brief mention) yet. Anyone should feel free to see if there’s an article to be written about any of them. For Tolkien, John Goldthorpe’s The Same Scourge and Alexander MacDonald’s The Lost Explorers. For Lewis, Vaughan Wilkins’s Valley Beyond Time and Charlotte M. Yonge’s The Trial.

Read on!

Dale J. Nelson may be contacted at extollager at gmail dot com.

Selected Articles by Dale Nelson

These articles go into detail on some topics mentioned in this interview. Where the article is available online, a link is provided.

“Days of the Craze #33: An Impertinent ‘Rogue’ Writes the First Book on Tolkien and Earns the Scorn of Harlan Ellison.” Beyond Bree November 2019: 7-9. (About William Ready’s Understanding Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings.)

“Days of the Craze #34: An Affectionate Look at A Look Behind at Fifty.” Beyond Bree January 2020: 4-5. (About Lin Carter’s 1969 book Tolkien: A Look Behind “The Lord of the Rings.”)

“An Easy to Read Modern Arthurian Epic.” Pilgrim in Narnia, 7 February 2018. https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2018/02/07/an-easy-to-read/. (About Martyn Skinner’s The Return of Arthur).

“Inquiring Minds: Bygone Days with Two SF-Loving English Professors” Portable Storage No. 2 (Autumn 2019): 40-49. https://efanzines.com/PortableStorage/PortableStorage-02.pdf. (About Brian Bond and U. Milo Kaufmann).

“A Jamesian Source for Tolkien’s Conception of Gollum?” Beyond Bree Jan. 2009: 1.

“The Lovecraft Circle and the Inklings: The ‘Mythopoeic Gift’ of H.P. Lovecraft.” Mallorn: The Journal of the Tolkien Society No. 59 (Winter 2018): 18-32. https://journals.tolkiensociety.org/mallorn/article/view/18.

“Lovecraft’s Comfortable World.” Fadeaway #53 (May-June 2017): 12-20. https://efanzines.com/Fadeaway/Fadeway-53.pdf.

“The Pageant at Willowton.” The Lamp, 27 January 2022. https://thelampmagazine.com/blog/the-pageant-at-willowton.

“Pictures and an Inner Vision.” Portable Storage No. 4 (Autumn 2020): 24-39. https://efanzines.com/PortableStorage/PortableStorage-04.pdf.

“Tolkien’s Further Indebtedness to Haggard.” Mallorn: The Journal of the Tolkien Society #47 (Spring 2009): 38-40. https://journals.tolkiensociety.org/mallorn/article/view/93.

“The Uncertain Legacy of Owen Barfield.” Touchstone vol. 11 #3 (1998): 36-38. https://owenbarfield.org/BARFIELD/Barfield_Scholarship/Nelson.htm.

Interviewer’s Notes

[1] See Brian C. Bond, “The Unity of Word: Language in C.S. Lewis’ Trilogy,” Mythlore vol. 2, no. 4 (Winter 1972): 13-15. https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol2/iss4/2.

[2] Walter de la Mare was friends with Owen Barfield and contributed an introduction to Barfield’s novel This Ever Divers Pair. Barfield’s grandson has noted that the novel fictionalizes Lewis (G. Connor Salter, “An Interview with Owen A. Barfield,” The Lamp-Post of the Southern California C.S. Lewis Society, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Spring/summer 2024): 3-30; 10. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48791314). This background connection makes it even more likely that Lewis would have been familiar with de la Mare’s works, even obscure ones.