BY G. CONNOR SALTER

William Lindsay Gresham helped put the word “geek” into popular American culture with his 1946 novel Nightmare Alley, a hardboiled tale that takes a behind-the-scenes look at carnivals… including the notorious “geek show” where a person pretends to be feral and eat live chickens and snakes. The geek as an image of what people will do to survive haunts the novel, making it an iconic if understudied classic in mid-century American crime fiction.

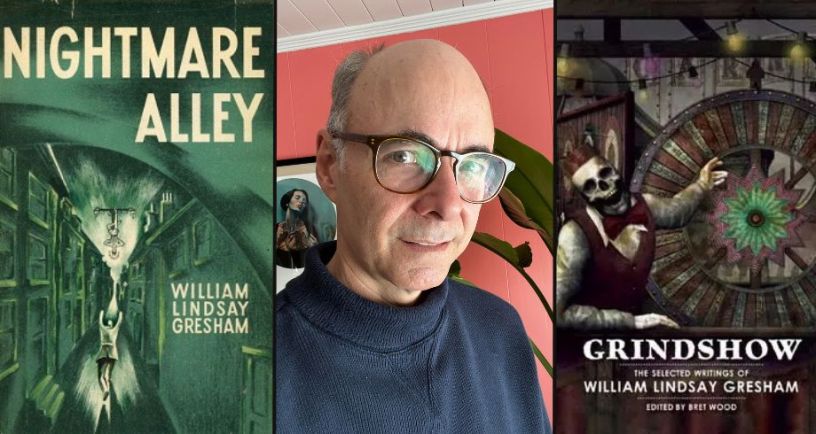

Several writers have produced important work on Gresham—both his fiction and nonfiction like his 1953 biography of Harry Houdini. One of the best profiles of Gresham’s life and works is Bret Wood’s introduction to Grindshow: The Selected Works of William Lindsay Gresham.

Wood is an award-winning independent filmmaker based in Atlanta, where he is the Senior Vice President and Producer of Archival Restorations for Kino Lorber. His works include the documentary Hell’s Highway: The True Story of Highway Safety Films and the horror film Those Who Deserve to Die.

Wood has also written for publications like Film Comment on under-explored films or filmmakers, as well as publishing books like Queen Kelly: The Complete Screenplay, and co-writing Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Film with Felicia Feaster. The same year that Centipede Press released Grindshow, Wood also contributed an introduction to the publisher’s special edition of Nightmare Alley, featuring two of Gresham’s articles on carnival/circus topics.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

How did you first learn about William Lindsay Gresham?

Back in the late ‘80s to early ‘90s, film enthusiasts would share VHS tapes they had recorded of their more interesting finds, whether it was a feature film or a mixtape of oddities. Because they knew I was interested in carnival culture (at the time, I was researching a book on director Tod Browning, several of whose films had carnival settings), someone gave me a bootleg of Nightmare Alley—which was not yet available commercially on video.[1] I liked the movie well enough to track down a copy of the novel, which I happily discovered was as good as the movie, only ten shades darker.

I was reading a lot of 1930s fiction at the time, especially interested in writers who straddled the line between literature and pulp (Nathanael West, Graham Greene, James M. Cain). So, Gresham was very much aligned with my interests, and I found in him someone whose life had not yet been adequately explored.

At this time there was no detailed bibliography of Gresham’s work, and his papers had yet to be donated to Wheaton College, so the only way to read his work was to embark on a literary treasure hunt. So, I, and a handful of others like me, spent a lot of time scouring libraries and way too much money on eBay trying to compile an authoritative list of Gresham’s writings and collect as many original copies as possible. He published a lot (170+ short works) in a wide variety of publications. And from this interest in his writing came my curiosity about the details of his life. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was often bidding against fellow Gresham enthusiasts Bramlett, Diego Domingo,[2] or Clark Sheldon, though we had yet to discover one another).

It seems that frequently, people either hear about Gresham from reading crime fiction and are shocked to discover his connection to C.S. Lewis, or they’re C.S. Lewis fans who hear Gresham’s name and are shocked to learn there’s more to him than the portrait we see in the play/movie(s) Shadowlands. How familiar were you with Lewis when you discovered Gresham?

Not very. I knew who C.S. Lewis was, primarily from my middle school reading list. I read The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, but nothing beyond that. I rarely read fantasy, and when I did, I seldom enjoyed it. For whatever reason, the magic of Lewis or Tolkien, Frank Herbert, or J.K. Rowling are lost on me. In 1978 my eighth-grade self was discovering Stephen King and my idea of engaging religious literature was the doom-laden comic book tracts of Jack T. Chick.

But it’s interesting now to come to Lewis in my fifties, and approach his work as a researcher, rather than as a reader. I think it’s going to take a lot of time for me to put aside the politics of Gresham and appreciate Lewis’s writings for its own merit. It’s an interesting reversal of the path taken by historians such as yourself and Perry C. Bramlett, who came to Gresham as a result of their interest in Lewis.

We know that Nightmare Alley is dedicated to Joy Davidman and that she gave feedback to many of his writings. Any insights into how she influenced the book?

I recall reading in correspondence that Davidman claimed to have rewritten the dialogue of not only the women characters of Nightmare Alley, but much of the men as well. I have to agree that she probably did, since there is a rhythm and naturalness in the dialogue, especially in the first half set among the carny folk. It is poetic in a way Gresham’s later dialogue seldom is. Gresham loved to pepper his dialogue with lingo, but it didn’t always come out naturally. We know from correspondence that Davidman enjoyed weaving slang in her language. She could launch a cute little word like “cookie” and make it land either as a term of endearment or a threat.

My favorite of Davidman’s writings are her film reviews (for the New Masses) where we see some of the same playfulness, shrewd intellect, charm, and venom that one finds in her correspondence—only now it was being aimed at an eclectic mix of Hollywood studio product and Soviet propaganda films.

Davidman also mentions having written portions of Monster Midway. Having been married to a writer/editor, I know the degree to which husbands and wives can rely on their spouses for feedback and suggested revisions. But I also know from personal experience that neither spouse wants to be reduced to proofreader of the other. Each wants to be the writer of the family. And so, I’m sure there was a degree of competitiveness between them that may have contributed to their alienation and eventual separation.

Not much has been said about Gresham’s second book, Limbo Tower. I’m curious, what’s your take on it—what works, what doesn’t work?

Limbo Tower is a typical sophomore effort, where the artist, swept up by the success of their first work, raises their ambitions to something more lofty.[3] And, under pressure to follow up quickly, Gresham could not take the time to finesse the novel. I also feel that 40 was a bit young for a writer to attempt to define a humanist philosophy spanning religions and races. He had found Christ, suddenly had the Answer, and maybe Limbo Tower commemorates a lightbulb moment in his life.

Joy Davidman once said of Nightmare Alley and Limbo Tower, “the two make up a picture of Gresham before and after Lewis.”[4] At this point in his life, Gresham had gone “From Communist to Christian”[5] and was just at the point of joining Alcoholics Anonymous for the first time. But he still had a great deal of searching ahead of him, a great deal more to suffer (separation from his children, cancer) before he could have written the book that Limbo Tower needed to be. But herein is one of the tragedies of Gresham’s career: he never had the luxury of financial independence. He used the initial Nightmare Alley proceeds to purchase a large house in Staatsburg, New York, neglected to set aside a portion of the payment for income tax, and spent the rest of his life trying to keep his head above water.

Gresham later alluded to a third novel, about hypnosis being used as a tool of persuasion and deception, inspired by his and Davidman’s experiences “running engrams” the analytical tools of L. Ron Hubbard’s Scientology.[6] Gresham had since become disenchanted with Scientology, and it is difficult to imagine what this novel would have been like, though it may have been too much a pastiche of Nightmare Alley, with hypnosis replacing stage mentalism. And instead of the intellectual Lilith Ritter, there might be a charismatic Hubbard figure in a jaunty sailor’s cap.

We talk a lot about the geek, but one of the quiet horrors of Nightmare Alley is the way psychoanalysis gets used as a tool for torment and manipulation. Ritter uses psychology as a stiletto or jiu-jitsu. Gresham was not cynical of psychoanalysis. He had been a patient at one time, and later in life regretted that he had been unable to undergo psychotherapy more often. He just saw the dramatic value of such a powerful method being employed with diabolical intent.

Given your work in film, I’m curious: what’s your opinion on the 1947 movie Nightmare Alley?

I like the film, but as noir goes, I rank it fairly low on my list of personal favorites, just because it was a real product of the studio system, and as such lacks the authorial voice of a director. It’s as good an adaptation as one could hope for, considering the time in which it was made. I’m just amazed that they were able to retain the novel’s bitter ending while operating within the guidelines of the Production Code.[7] So for that reason alone, the film is a wonder to behold.

Any thoughts on the more recent Nightmare Alley movie directed by Guillermo del Toro?

I really appreciated the way del Toro blended a traditional film noir approach (it’s worth noting that he did also release a black-and-white version of the film) with something so carefully crafted, like a jewel box or a storybook. It’s true to the spirit of Gresham, yet it is entirely his own.

I found the performance of Cate Blanchett as Lilith Ritter distracting. I had too much of a fixed idea of what the character of Lilith should be like: plain in appearance, bookish, almost asexual. She’s one of the grain villains of literature because we at first don’t think she is dangerous. Just another woman for Stanton to use and discard. So, to see her depicted as this silken seductress — it turns her from a truly enigmatic figure into an obvious femme fatale.[8] At times Bradley Cooper seems to be playing Stanton as a literal Fool, so maybe that explains why he couldn’t see his fate when it was so apparent to the viewer.

In my opinion, the Lilith character is a combination of Jean Karsavina (the novelist and CPUSA member with whom Gresham had a long relationship) and her fellow writer and CPUSA member Joy Davidman. Gresham was clearly attracted to this kind of New York intellectual, who also had a codified look. In 1990, Gresham’s sister-in-law Mary Ellen Gresham (she was married to his brother),[9] addressed the misperception of Joy Davidman’s appearance as unattractive:

“She was not ‘dowdy’ and unattractive. She gained weight when she was ill, before that, she had a nice figure, “zoftic” [zaftig] type in Yiddish. That is, not fashion slim, but pleasingly fleshed, without dumpiness. She had a fine olive complexion, good color, well middle parted hair, pulled back in a bun, was precisely what Gloria Steinem’s downplay of natural attractiveness was, a defiance of New York Jewish women’s emphasis on making as good as an appearance as possible, as a sign of prosperity. It was also, with both, intended to show intellect does not need feminine attractiveness, the mind is what matters, not the ‘feminine’ that men so often look for first.”[10]

That checks with Nightmare Alley itself, where Ritter is hardly glamorous but almost intentionally nondescript: “This dame wasn’t fat, she wasn’t tall, she wasn’t old. Her pale hair was straight and she wore it drawn into a smooth roll on the nape of her neck. It glinted like green gold. A slight woman, no age except young, with enormous gray eyes that slanted a little.”

No photos are known to survive of Gresham’s first wife, Beatrice McCall, but a snapshot of his final partner, Renée Rodrigues Gresham, shows off her striking features, hair pulled back into a bun at the neck.

I know your book Forbidden Fruit is about exploitation films specifically, but I’m curious. Do you see any overlap between noir and exploitation?

Oh, for sure. They are both set in this American underbelly that seems to always attract my interest.

Exploitation films were independently produced low-budget movies of the 1930s. The hook of the exploitation film is that it would proclaim itself educational, it would begin with a long title scroll, citing police and medical authorities, explaining why these issues would need to be frankly addressed in this motion picture. And they would make films about drug abuse, syphilis, polygamy, and child marriage. If it was in the Hollywood Production Code of forbidden topics, they probably made a film about it.

These were low-budget black-and-white films on grim topics, so they fit right alongside noir cinema. But they bear an even greater resemblance to the carnival world which so fascinated Gresham.

These films were often exhibited as “roadshow” attractions, with elaborate (sometimes gruesome) lobby displays, live lectures by phony medical authorities, and of course souvenir booklets being pitched by the lecturer. Gresham would have made a good exploitation pitch man, and could have milled some wonderful stories from its grist.

Who knows, if Gresham had spent time with an exploitation roadshow person during the Spanish Civil War (instead of a carnival veteran), Nightmare Alley might have been a very different novel.[11]

Next week, Part 2 of this interview will discuss Wood’s time interviewing Gresham’s wife and his book Grindshow: The Selected Writings of William Lindsay Gresham.

(Article first published November 15, 2024).

Footnotes

[1] This may be because a lawsuit involving producer George Jessel kept the movie from being released on video for some time, and sometimes limited its being broadcast on TV. The movie appeared in various late night TV showings, festival screenings, and bootleg videos for decades before it was released on an authorized DVD in 2005.

[2] For Domingo’s description of his interest in Gresham, see G. Connor Salter, “William Lindsay Gresham, The Inklings, and Magic: An Interview with Diego Domingo.” Fellowship & Fairydust, February 7, 2024.

[3] It’s worth noting that Gresham spent a year attempting a similarly lofty project, a novel inspired by his Spanish Civil War experiences in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, before burning it and writing Limbo Tower (Bret Wood “Introduction,” Grindshow: The Selected Works of William Lindsay Gresham [Centipede Press, 2013], 9-39; 20-21).

[4] June 21, 1949 letter to Chad Walsh. See Don W. King (ed.), Out of My Bone: The Letters of Joy Davidman (Wm.B. Eerdmans, 2009), 104-105.

[5] In 1950, Gresham published a three-part article series in Presbyterian Life called “From Communist to Christian” discussing his spiritual journey.

[6] Gresham and Davidman became interested in Hubbard’s book Dianetics when it appeared in 1950, and practiced auditing for several years.

[7] Jonathan Brielle discusses how the movie combines the dark ending with a redemptive final moment, and Renée Rodriguez’s memories about how Gresham felt about this adjusted ending. Kim Morgan has discussed how it perhaps inadvertently makes the ending darker, suggesting that the characters Stan and Molly will repeat the tragic roles of characters Zeena and Pete (“Nightmare Alley: The Fool Walks in Motley…” Criterion, May 25, 2021).

[8] It may be worth noting here that Spain Rodriguez also falls into this trope, making Ritter an attractive figure from the start in his graphic novel adaptation. Diego Domingo has noted that the graphic novel deliberately combines Ritter with another set of cultural cliches: illustrations of her sexually manipulating Stan Carlisle resemble layouts from 1950s adult magazines (email conversation with G. Connor Salter, “Some odd Gresham research,” February 5, 2024).

[9] Henry “Hank” Lindsay Gresham. Both sons received their mother’s maiden name as a middle name.

[10] Mary Ellen Gresham to Kathryn Linskoog, 5 December 1990.

[11] As Gresham discusses in Monster Midway, the novel was inspired by conversations he had with a carnival employee Joseph “Doc” Halliday, during their service in the Spanish Civil War. For more details on their friendship, see Ben Iceland, “Last Months in Spain,” The Volunteer, September 24, 2015.