BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Dr. Amanda B. Vernon (PhD, Lancaster University) is a specialist in Victorian literature and theology. She has taught at Lancaster University, Anglia Ruskin University, and at the University of Tübingen. Her research has appeared in various publications, including Victorian Review, Victorians: A Journal of Culture and Literature, The Journal of Inklings Studies, and Among Winter Cranes.

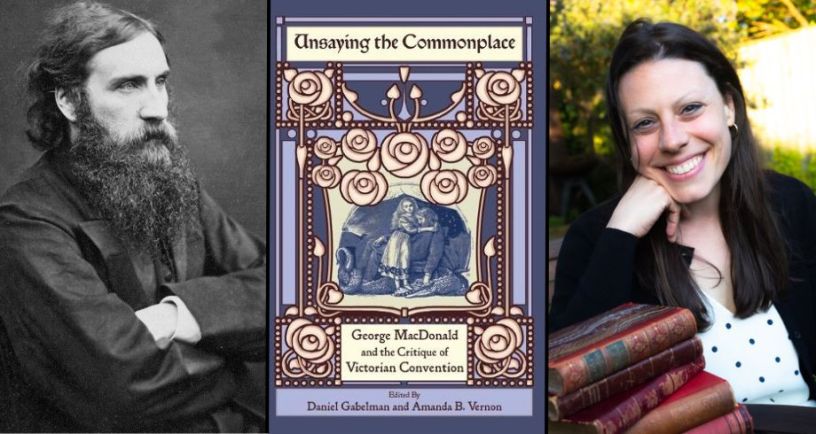

Much of her work has focused on George MacDonald, the Scottish writer and theologian whose work ranged from fairy tales to realist novels. MacDonald influenced many thinkers, including J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Madeleine L’Engle. Vernon co-edited with Daniel Gabelman the essay collection Unsaying the Commonplace: George MacDonald and the Critique of Victorian Convention. She will also contribute to the upcoming Cambridge Companion to George MacDonald and her first book, the monograph Reading with the Trinity: Theology and Literary Form in George MacDonald, will appear in 2026.

She was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

What was your first exposure to George MacDonald’s work?

I read MacDonald’s fairytales when I was a child. I have a vivid memory of being terrified of the long-legged goblin creature that Irene runs away from in The Princess and the Goblin!

Were you interested in Victorian literature already, or did that grow out of your work on MacDonald?

The former!I’ve always been drawn to Victorian literature and gravitated towards that during my undergraduate degree. I decided to write my undergraduate dissertation on the role of the imagination in Jane Eyre and Alice in Wonderland (a bit random, but it worked!). I was reminded of MacDonald when I was reading Stephen Prickett’s Victorian Fantasy for that dissertation. I got my hands on a copy of The Princess and the Goblin and was astonished by how theologically rich it was. That intrigued me and I ended up focusing on MacDonald’s fairytales for my Master’s dissertation.

MacDonald can be a specialized topic, under-researched compared to people he influenced like the Inklings. Were you able to connect with other scholars who supported your work?

I was fortunate to have met Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson at a conference in Cambridge in 2016 as I was trying to decide whether I wanted to pursue PhD study. Before that I hadn’t come across anyone working on MacDonald or specialising in theology/religion and literature (although my supervisors and lecturers along the way were very supportive, which was lovely). Kirstin is a massive cheerleader and kept encouraging me to pursue my work on MacDonald. I was then doubly fortunate to connect with my PhD supervisor, Mark Knight, who was very supportive of my project on MacDonald’s literary criticism. While there are fewer scholars in mainstream academia working on MacDonald, people have shown a lot of interest in him when I’ve spoken about my work at conferences, etc. MacDonald does seem to be popping up more and more in Victorian studies, which is exciting.

Perhaps I’m mistaken, but it appears as if most people focus their attention on MacDonald’s fantasy literature (The Light Princess, Phantastes), less on his realistic fiction and his nonfiction. Any thoughts on what the barrier has been?

I think that’s a fair assessment. MacDonald is doing some really interesting things with his fantasy writing and, of course, has influenced fantasy writers from Tolkien and Lewis to LeGuin and Gaiman—so perhaps that is why people have gravitated towards that aspect of his writing. In terms of the non-fiction, I’ve heard from various people that they find his style difficult. I wonder if that might be part of the problem…Victorian prose! Personally, I don’t think his non-fantasy novels are executed as convincingly as those of other nineteenth-century writers (say, George Eliot). If you like MacDonald’s spiritual ideas then you’re probably more apt to enjoy the novels, though, and be less resistent to the more didactic moments. I think his novels are interesting for various reasons, though, and so I continue to read them with enjoyment. I like thinking about how he uses them as a way of exploring his theological ideas and instructing people on how to read literature, as well as the window they offer into Victorian culture. He also depicts mentally-afflicted characters with a sensitivity that I think is quite remarkable.

I have found when speaking with others that Phantastes seems to be a book people love immediately or find intimidating and hard to get through. Any suggestions for first-time readers?

I would say to follow the Novalis epigraph at the beginning of the novel and simply go along for the ride. Don’t focus on trying to ‘decode’ things, you’ll probably end up frustrating yourself and not enjoying the book! MacDonald intended his fantasy work to affect you and stir things up in you—he wanted your emotions and imagination involved before your intellect. Another thing I’d say is not to rush reading it. The novel is full of the most lush descriptions and if you slow down and read it like poetry, or in a slow, meditative way, you’ll enter into the realm of faerie with much more ease!

You’ve written in your essay “A Form of (Spiritual) Knowing” about how MacDonald’s understanding of the way poetry communicates information enriched his understanding of prayer. Anything else you find notable about MacDonald’s perspective on poetry?

One thing MacDonald focuses on in his critical work on poetry is something that I think we might have a tendency to lose in academic work: aesthetic enjoyment! For MacDonald, it wasn’t enough to analyse a poem, to really ‘get’ it you need to feel it. I think we could make a bit more space for a balance between intellectual engagement (which, as a literary scholar, MacDonald certainly did and then some!), and unabashed enjoyment of the literary works we read. My experience with many of the people interested in the Inklings is that they’re really good at holding these two things together. MacDonald would be very pleased!

Your essay included in Unsaying the Commonplace touched on another Victorian Christian fantasy author: Charles Kingsley, author of The Water-Babies. What are some ways he compares and contrasts to MacDonald?

There are a lot of differences between the two writers (and the fairytales that I look at in that chapter): style, ideas about the relationship between science and theology, approach to social issues, etc. One thing that stands out to me, though, is the level of trust MacDonald places in his reader as opposed to Kingsley. The latter often seems worried about controlling interpretation or the dangers of writers who are more mystical or vague. For instance, Kingsley warned his wife away from reading the German Romantic poet Novalis (a favourite of MacDonald’s), because ‘you never know much he means’. MacDonald, on the other hand, had a trust in his reader and a willingness to learn from the interpretations of others. He writes in his essay ‘The Fantastic Imagination’: ‘It may be better that you should read your meaning into [his fairytale]. That may be a higher operation of your intellect than the mere reading of mine out of it: your meaning may be superior to mine.’ Part of that trust for MacDonald is an awareness and welcoming of the work of interpretation. It is also a trust in the Holy Spirit, who he believed to be working in the imagination, revealing truth to each person as they were able to receive it.

What are some MacDonald topics you would particularly like to see scholars explore in the near future?

Ah, so many wonderful things to explore! I’m particularly keen to see more work done on MacDonald in his Victorian context, so I would love to see an exploration of his relationships with, and influences on, proto-feminists and social reformers like Josephine Butler and Octavia Hill. I’d also love to see someone dive into his connections with the Pre-Raphaelites. That would be fabulous!

Are there any other Victorian authors you hope to explore soon?

Yes indeed! Unlike my PhD, my next project is thematic rather than single-author focused. I’m expanding out to look at the idea of therapeutic reading (or bibliotherapy as we’d now call it) and spritual practice in the Victorian period. MacDonald will feature, but I’ll also be looking at Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and George Eliot (amongst others!).

Any upcoming articles, podcast interviews, or other projects you can share with us?

Apart from my monograph and the Cambridge Companion chapter,I’m writing a little piece, ‘Growing Younger with George MacDonald’ to celebrate MacDonald’s bicentenary in December. It’ll be available to everyone in the ‘Discover Literary Anniversaries’ section of Connotations, a journal that comes out of my department at The University of Tübingen:

https://www.connotations.de/2021/03/05/discover-literary-anniversaries/

More information about Amanda Vernon’s work can be found on her website.