BY G CONNOR SALTER

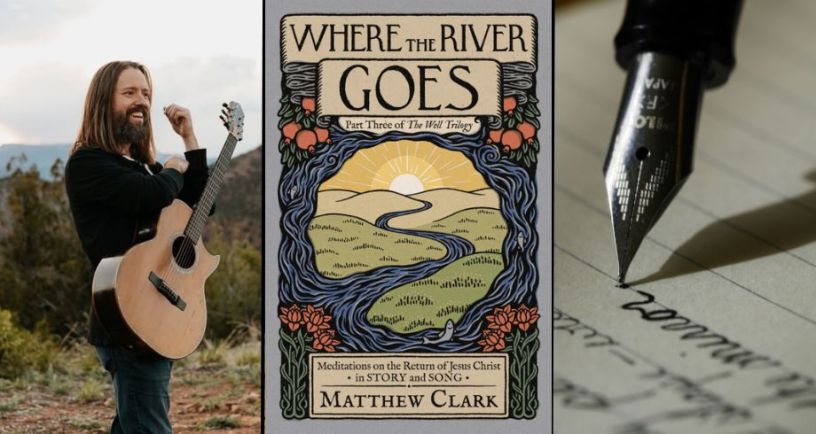

Songwriter Matthew Clark has written multiple albums based on biblical themes, but his latest one offers more than just lyrics and music. Where the River Goes is an album with a companion book containing reflections by Clark and other writers about restoration, mourning, and grief. The project is the culmination of the Well Trilogy, which Clark started with the 2022 book Only the Lover Sings and continued with A Tale of Two Trees.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions about the Well Trilogy and the journey to realize this project.

Interview Questions

For readers who have not gotten a chance to read Only the Lover Sings, can you share how the Well trilogy began?

Back in the fall of 2019, I was about to leave for a three-month house concert tour. I had about 50 or so song ideas recorded on my phone that had accumulated over the previous few years, and I decided to put them all on a big playlist I could listen to while driving around the country. The more I listened, the more I felt like the songs naturally seemed to group themselves into three conversations. One was about encountering Jesus and all the obstacles and surprises involved. Another was about holding on to a relationship in hard times, and another seemed to be about the joy and relief of a happy ending. I didn’t go looking for it, the songs just seemed to cohere in that way. I hadn’t been thinking of doing anything like a trilogy, but there it was.

The more I listened, the more excited I got. It hooked my imagination, and themes started to emerge. John 4, where Jesus goes to Samaria and meets the woman at the well, had been an important scripture scene for me. The Lord had been using it to help me heal after a divorce for a while. That became the framework for understanding the first group of songs that were about encounter, obstacles to encounter, and ultimately surprise and joy in that encounter with Jesus at the well. Then, Psalm 137, where the exiled Israelites are deciding whether or not give up on singing the songs of Zion, became the frame for the second group of songs about faith-keeping. Finally, Ezekiel 47 and Revelation became the frames for the last group of songs about the final defeat of sin and death, where, in the end, God’s dream for his world is fully realized.

That makes it sound like it happened quickly, but there was a lot of just hanging around these songs and dreaming about the project, watching a blurry idea become a clearer and clearer picture. Then, when the pandemic hit the following spring of 2020, I decided, since I couldn’t tour, it would be a good time to hunker down and finish writing all the songs. By then, I had a kind of “storyboard” in my head as the songs had taken a more definite shape and sequence. I just needed to spend a few months strengthening the ones I had and writing the ones that were missing from that sequence.

Pairing a book with an album can be a challenge. Did you have any models to draw on when you started—Michael Card’s books on biblical figures, anything like that?

Not really. I’ve never actually read or listened to any Michael Card, though I really enjoyed hearing him speak at Hutchmoot some years ago. I didn’t grow up being very aware of Christian music, really. My youth minister tried pretty hard, but I was way too cool for Christian music growing up. Eventually, I warmed up to Rich Mullins and Mark Heard.[1] As a guitarist, Phil Keaggy was very easy to love. Sara Groves is a favorite, and eventually Andrew Peterson and the Rabbit Room crew.

Really, I’ve just always loved books. Growing up, I had zero athletic interest or ability. I tried to throw a spoiled mini-orange about 20 feet over the backyard fence the other day, and my arm almost came off with it. And the orange didn’t make it over the fence. So, bad at sports, and actually pretty bad at school. I read books and played guitar. That was my thing.

Over the years, I’ve gotten to know a lot of wonderful writers, and dabbled in writing myself. When the songs took shape as a trilogy of albums, I thought, “What if I made some books to go with the albums? They could be like massively expanded liner notes, like physical albums used to have. What if I invited writers I admire to choose a song and respond with a personal narrative essay?” I ran the idea by Diana Glyer,[2] who wrote a book on collaboration called Bandersnatch, which is about Tolkien and Lewis and their writing group, the Inklings, that had been challenging me to invite other people into my work. I asked her if she thought this was a stupid idea, and she assured me it wasn’t. That gave me the affirmation that I needed to move forward. Then, amazingly, writers said “yes” to the invitation, and we started putting together the Well Trilogy, with this combination of albums and books.

While every story about Jesus is certainly memorable, I suspect most of us would feel intimidated at writing multiple books about a short story like the Woman at the Well. How did you decide to explore this story over three books instead of one?

Good question. That’s one reason I structured the books as essay collections by a variety of writers. Honestly, at the beginning, I did not feel confident that I could make a book at all—much less three. It was very intimidating. I had some conflict with the Lord about it, and it became clear that the confidence I wanted wasn’t owed to me and, thankfully, wasn’t a prerequisite to doing the work. He was teaching me that my job was simply to make something of the love I’d been shown. Make something, send it out, the rest was none of my business.

At any rate, the shortness of the story wasn’t the problem. Humans have “eternity in their hearts,” Ecclesiastes says. When it comes to stories about people, there’s no such thing as “getting finished.” Personhood, by nature, has an endlessness to it. Our personhood is nestled in and derived from God’s, and so when you put Jesus and this woman in proximity in this scene, there’s a kind of generativity of meaning that never runs dry. In the terms of the story itself, it’s like living water that just continues to well up forever. And that’s just one tiny passage in Scripture, but it’s indicative of the whole. People are just like that somehow—relationship is just like that somehow.

Again, the trilogy wasn’t strictly my idea. It just took shape that way. Meaning is not something you have to fabricate or invent. It’s already there. You have to practice a certain posture of attentiveness and care in order to participate in it, and it takes a lot of patience with the process for the blurry thing to become clear, or for the folded thing to unfold. You can’t expect intimacy to develop without a carefully kept habitat, right? Art-making is like that. The central skill is something like careful listening, attentiveness, and participation. Love, basically. Art gets made because someone begins to feel love might be directed their way, and they vulnerably venture to love that love back. Then they “make something of that love.”

You talk honestly through all three books about empathizing with the Woman at the Well, particularly after a crisis challenged you to consider your priorities. Was this the first time you’ve published about that difficult time?

You know, I used to work at an inner-city summer camp. Youth groups would come from all over and serve in what to them was a very impoverished place. At the last chapel of the week, we’d have a sharing time, and the majority of them would say something like, “I didn’t realize how poor some people are, so from now on I’m going to really practice being thankful for what I have.” We understood that response, of course, so I’m not beating up on those kids, but it also frustrated us. It was sort of missing the point. They mistook the suffering as a challenge to straighten out their priorities. To do better.

Your question clarifies something for me, because it reminds me that the experience of a traumatic marriage and divorce didn’t make me consider my priorities so much as it just rendered my life completely incomprehensible. It blew everything to bits, and nothing made any sense to me. My only priority was to not die. I mean that in the most literal, desperate sense. I couldn’t imagine anything better than dying for a time. I had no imagination or heart for life at all. Maybe it was only shame about feeling that way that kept me from enacting anything? I don’t know. That and the people in my life who didn’t disappear.

In the middle of that, the Samaritan woman snuck up on me. I wasn’t looking for that story. It just showed up, and kept showing up over and over. A podcast here, a “random conversation” there, and so on. I see now that the Lord was making sure it kept crossing my path. Eventually, I came to see that this woman’s life and mine were similar. After so much trauma and loss, neither one of us had any heart or imagination left for seeing the possibility of anything good up ahead of us. And both of us were wrong. Both of us were in for a surprise.

The process of sitting with that story and all that led up to making the first album of the Well Trilogy, Only the Lover Sings, took about seven years. When that book came out, it was the first time I’d published about those experiences. But I wasn’t nearly as raw by then. Not that I wasn’t scared to put it out there, I was! But I’d done a good bit of healing and felt like the Lord had re-cosmosed enough of the chaos that I was ready.

Some time ago, I was listening to a talk you gave at the Anselm Society, where you mentioned being advised early in your career that art is made in collaboration with others. Did that shape your decision to make these three books into collections of reflections from different writers, instead of just your thoughts?

Yes, collaboration didn’t come naturally or easily to me. I resisted it. Early on, I had a mentor who called me out on it, and it just made me bitter. I was maybe 20 at the time. It was a long process, maybe 15 more years, of slowly learning that whatever false sense of control or invulnerability I got from working alone wasn’t worth it. My own stuff was getting very boring to me. I couldn’t surprise myself in a closed system. I looked around and I saw all the artists I admired and whose work moved me the most, and realized that they were all deeply collaborative. Tolkien, Lewis, Rabbit Room folks.

I mentioned Diana Glyer’s work on the collaborative fruitfulness of the Inklings that produced some of my favorite books, like The Lord of the Rings and Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy, and I finally caved. I’d been inching towards collaboration for a while, but at that point, I decided to intentionally create a project that would require it of me. To force me to immerse myself in that interdependence. It’s been very challenging at times, but absolutely worth it. It’s been so good to practice getting over myself a little.

The books have some impressive contributors, including people who make art in many media—poets like Malcolm Guite, visual artists like Ned Bustard. What would you think we gain when we have multiple kinds of artists sharing their stories?

People are irreplaceable. If we were just machines you could get new parts, switch this one out for that one. I think it’s telling that Paul says the church is like a body. I guess he could have said it was like a weaving loom, or some other complex mechanism. We’re back to personhood again, right? Part of the fun of collaborating is being surprised, because I can’t predict (and I was deliberate about not micromanaging) what the essayists brought to the project. I picked people I felt I could trust to show up in a rich, vulnerable way, and then I had fun being surprised by how the absolutely irreplaceable particulars of who they are showed up.

Life has patterns and real meaning, so as those surprising particulars are offered up, the Holy Spirit connects our hearts in compassion and shared reality. It was fun to involve writers from different disciplines, because the ways of seeing and engaging with the world that they’ve picked up by loving the specific materials of their craft come through in the what they thought to say and how they thought to say it. I don’t see things the way a painter does, or sculptor, or a parent, or a foster parent. But God has made us so that our inner worlds are communicable, transmittable… the One who dwells in the bosom of the Father has come to make the invisible God known to us, John says in the prologue to his gospel. God discloses himself to us, so that his heart can enter into ours and vice versa. People can do that, so I can enter in and learn from someone who is very different from me and begin seeing things that I wouldn’t otherwise have seen or known.

Did your understanding of the Woman at the Well grow or change as you read the different thoughts each contributor brought to the project?

Absolutely. Jesus says that the reason he tells parables is to put a lamp on a stand, but they require investment. You get about as much out of them as you’re willing to put in. Any relationship, any story is like that. So, naturally, hanging out with a bunch of people all paying attention to similar things will grow and change you according to the direction of that attention. The more you walk in those woods, the more you get to know the trees. But, there’s a lot of trees! So, walking with friends gives you the benefit of what their attention is able to gather, too. Then you can tell each other stories that’ll help you see more than you ever could have seen on your own. Those stories give us the courage to keep walking, to stay on pilgrimage toward the Joy set before us.

You give a memorable example in the introduction to Only the Lover Sings about the blessing that Christian community can be—someone who offered a room you could stay in for a while so you could work on the songs without distraction. When you talk with other Christians who make art, what advice do you give them about finding good community?

Yes! Steve and Terri Moon, who I met through the Anselm Society out in Colorado Springs, invited me to come live with them for as long as I needed to work on the songs. I’m still amazed by that. At the time, we knew each other a little, but we were not super close. It was a risk and an experiment for both sides. But they were incredibly generous.

Something I realized was that the notion that, as an artist, the ideal would be to hide away in a cabin by yourself to work on your art was not really as great as it sounds. I did have distractions, but they were the kind that make life feel like living. So, the game changer for me was being incorporated into the daily rhythms and routines of family and home life with the Moons. I really believe that’s what made things work. It was communicated that I’d protect a pretty solid schedule, working something like 9-5 on the songs, but I wasn’t alone. I was situated in a family habitat. We ate meals together, went on walks, watched movies, they hugged me every morning at coffee and every night before bed. I’d play the songs for them and get their feedback in real time. It was an incredible experience, and it was very hard to leave when the time came at the end of 10 weeks.

My advice would be to be on the lookout for folks you might invite into your life and creative processes. Don’t assume no one wants to help. And don’t assume you don’t need any help. Being alone goes against the grain of our nature.

Reading Where the River Goes, I was struck by how honestly the Well trilogy addresses grief—the grief some writers felt from losing loved ones, the grief we are all feeling in the aftermath of the pandemic, how grief is written into the story of the Woman at the Well. Yet the book also avoids angst, it’s very much about what J.R.R. Tolkien called eucatastrophe—the promise of renewal after pain. Would you say it’s important we affirm both sides of that story—the pain as well as the renewal, Good Friday and Easter Sunday?

One of the major themes across Scripture, it seems to me, is vulnerability, which is a word that means “able to be wounded.” Humanity has all this capability and power, but we’re also incredibly vulnerable. It’s scary to be a human. Things like angst, bitterness, cynicism, sarcasm, even bravado… they’re understandable ways of coping with the fear inherent in being vulnerable, but they only simulate safety and peace.

Surprisingly, the most vulnerable person in Scripture winds up being God himself. The person who risks the most in relationship, puts his heart on the line more than anybody, is the Lord. The one who experiences intense disappointment, frustration, rejection, and, in the New Testament torture, brutalization, and murder turns out to be God. If anybody knows how terrifying and miserable it is to be vulnerable, it’s our very wound-able God. Christ’s invitation now is that we abide together, and maybe you could think of that as an invitation to enter into each other’s wounds? To die and grieve with one another. God knows what it’s like to suffer as a human, can we have compassion on God and learn from him what it’s like to be as vulnerable as he is? That seems to be a protection against simulated peace, because the shared experience moves us into union rather than coping which creates false, protected selves that can’t make true contact.

Jim Wilder, a favorite of mine, says that joy is not the absence of pain, it’s discovering someone is glad to be with you in it. Accompaniment, connection, attachment, intimacy—that’s where joy comes from. Finding someone is glad to be with us even in the most miserable places. That the cross, though, isn’t it? It’s God saying, “Yes, even here in the middle of all this nakedness, shame, and misery… I want to be with you.” Someone said that at the scene of the crucifixion there was only one person who actually wanted to be there.

As that becomes clear we can relax and just let ourselves rest against Jesus’ bosom, like John at the last supper. The Resurrection is exciting, of course, but the main idea for me is that it means Jesus has cleared all the obstacles to us reaching the destination we were made for: to be with and like Jesus. That “eternity he has set in the hearts” of humanity will outlast every death, because of what Jesus has done in love for us. Meanwhile, the call is to follow the pattern of reality (the Life of the Trinity) revealed by Jesus, which is vulnerability.

You make an important point in the introduction to Where the River Goes: “you can’t grieve a false narrative and you can’t grieve it alone.” What has helped you to seek true narratives about pain?

That’s right. The title track of the first album says, “You’ve never met a liar / you’ve only met the lie that they put forth / There ain’t no soul more lonely / until you tell the truth / you can’t be touched.” So, a lie isn’t real. It’s an un-reality. If you grieve a lie, you haven’t made contact with what’s actually going on, so don’t be surprised if you can’t get anywhere new in your life. One of the big themes across the Trilogy is this idea of facing. Can we face reality? What if the reality is we were abused, or we’re addicted, or something like that? It becomes too painful to face. Depending on how bad it is, our brain and body may literally be unable to deal with it and we dissociate, we sever that part of ourselves.

The only thing that can give us the strength to face our own stories of what we’ve done (shame) and what’s been done to us (trauma), is to be held lovingly by another person… to be faced in love. Without being located like that in a context of reliable, tender love we just can’t stand to face the pain of life. Instead, we live in an un-reality, and rather than faces, we construct façades, which protect us from making real contact with other souls. That’s tragic. Instead, we’re just façades bumping up against other façades, you know? The only outcome there is loneliness.

Jesus is trying to get us out of that trap. Again, the woman at the well is an example. By the end of that conversation, she’s able to face herself and her own sad story with joy, because she’s been faced with such incredible love by Jesus. She goes “singing” all over town about this man who knew all about her shame and yet came to make real contact in love. The lyric to the song “Meet me at the Well” goes, “When I saw you seeing me / it was the first time I could see / that I was loved completely.”

The Samaritan woman also goes and invites her town into what’s going on, right? By the end, the healing work of Christ has called a community together. Everyone in that town is invited to come before the face of God and be surprised by his love, which will enable them to shed their façades and live with real faces, to stop living a false narrative.

But you can see how the world is so terrified. We spend a lot of energy avoiding Jesus’ face. So did the Samaritan woman. Her wounded imagination just had no room for the look of tenderness and joy on Jesus’ face toward her.

I imagine you’re busy celebrating the Well trilogy being fully realized and finished, but can you share any future projects?

Ha! I’ve got a document on my Google Drive with about 10 or 12 different projects I’d love to work on. I’d love to make an instrumental guitar album. I’d love to maybe re-work a Bible Walk-through album I made in 2012 called Bright Came the Word from His Mouth. After this book, maybe I’ll have more headspace to get back to making my podcast, One Thousand Words? I also just kind of want to go hide somewhere and take a long nap.

Where the River Goes will be available for purchase on April 17. More information about the album and book, as well as the first two installments of the Well Trilogy, can be found on Clark’s website.

Interviewer Footnotes

[1] Heard’s biographer Matthew Dickerson, spoke about his work to Fellowship & Fairydust in this 2024 interview. https://fellowdustmag.com/2024/03/06/fantasy-author-interview-matthew-dickerson/.

[2] For more details on Glyer’s work, see her 2024 interview with Fellowship & Fairydust. https://fellowdustmag.com/2024/01/24/diana-glyer-talks-the-major-and-the-missionary/.