BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Corey Latta has many interests. He earned his BA in Biblical studies at Crighton College, and has since taken three Master’s (New Testament Studies at Harding School of Theology, English at the University of Memphis, Counseling at Concordia University) and a PhD (English, University of Southern Mississippi).

He has written on many of these interests. His first book, Election and Unity in Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, appeared in 2009. In 2017, he co-authored Titans: How Superheroes Can Help Us Make Sense of a Polarized World with Armond Boudreaux. He has also written about superhero movies and apologetics for Christian Research Journal, about Walt Whitman for CEA Critic, and both Othello and Hamlet for An Unexpected Journal. Among other things.

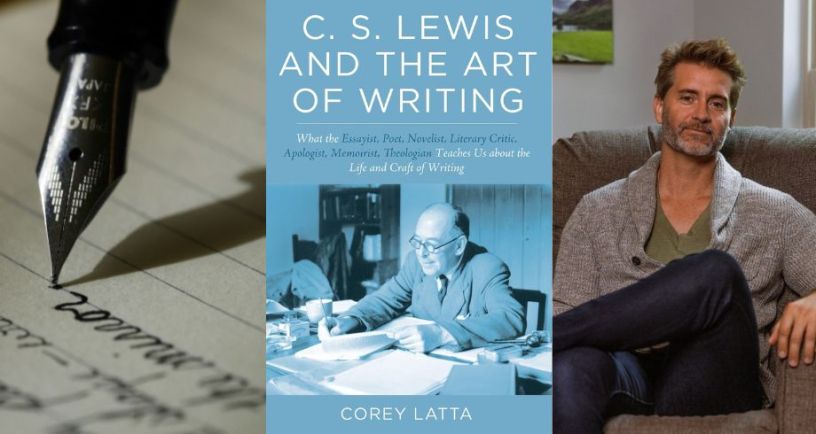

One continuing thread in his career has been the Inklings. His first book on the Inklings appeared in 2010, Functioning Fantasies: Theology, Ideology, and Social Conception in the Fantasies of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. Since then, he has published When the Eternal Can Be Met: A Bergsonian Theology of Time in the Works of C. S. Lewis, T. S. Eliot, and W. H. Auden (which began as his doctoral thesis) and C.S. Lewis and the Art of Writing: What the Essayist, Poet, Novelist, Literary Critic, Apologist, Memoirist, Theologian Teaches Us about the Life and Craft of Writing. He has also contributed a review of Paul Kerry’s book The Ring and the Cross: Christianity and the Lord of the Rings to the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

What was your first encounter with the Inklings?

I’m curious how many other lovers of the Inklings have a similar story, but I actually came to the Inklings through Peter Jackson’s trilogy, first seeing The Fellowship of the Ring in theaters in December of 2001. I had a very elementary knowledge of C.S. Lewis, and if I recall correctly, I read Lewis’s sermon, “The Weight of Glory,” for the first time early that year. But it was the big screen that led me to the page. Immediately after seeing Fellowship, I bought a paperback copy of The Lord of the Rings and just dove in.

That very next spring, I took a senior-level class on Tolkien, which served as a wonderful capstone to my undergraduate work. I was a biblical studies major, but my last semester took a “fantastic” turn as I started reading Tolkien and Lewis in earnest.

What led you beyond being a fan of the Inklings to studying their work?

Back to that senior level Tolkien seminar, which was very well taught, I was fortunate enough to read Leaf by Niggle and The Hobbit that same term. This exposure to Tolkien compounded with what became an absolute obsession with the Lewis’s work served as a threshold for me. I went straight into seminary after graduation and while my academic focus was New Testament studies, most of my time went to reading Lewis, Tolkien, and eventually Charles Williams. I began a MA in English while completing my seminary degree, and I tied almost all of my work to modernist literary and the works of Lewis and Tolkien. I did a minor in children’s literature and wrote as well as presented quite a bit on The Hobbit and the Chronicles of Narnia.

Your book on Bergsonian time discussed some common ideas between Lewis and Eliot—two writers we tend to think of as opponents. Were you surprised to see they had common ideas?

Yes, especially given the notable tension between them. Though, because of their conversions to Christianity, Eliot’s to Anglo-Catholicism in 1927 and Lewis’s to Anglicanism just a few years later in 1931, it makes sense that they would find some theological common ground. And I think, because of the prominence of Bergson’s ideas and because of just how influenced both Lewis and Eliot were by him, they were bound to line up in some areas.

How do you balance having, and writing about, so many diverse interests?

Balance? Is that French?

I’m terrible at balance. I do things in obsessive sprints, lots done in short periods of time, several lines of interest crashing into and cancelling out others. Somehow, it all seems to work. I think.

You mention in your book C.S. Lewis and the Art of Writing that it began as a scholarly research project, before you redirected to make it a more accessible book that a larger audience would appreciate. What kind of responses have you gotten from readers?

Gratefully, I’ve received overwhelmingly positive responses from readers. It’s exactly because it’s accessible that it’s been received well. The most common feedback I receive is appreciation for the “Do Try!” section at the end of each chapter, which leaves readers with a writing prompt.

One of your insights is how Lewis adopted a simple writing style. During your 2023 presentation at the Marion E. Wade Center, you noted that Pilgrim’s Regress has the same writing level you see in your nine-year-old son—simple and clear. How does that simplicity affect you as a reader?

Personally, I find it massively refreshing. Of course, Lewis is also a complex writer. At times, a difficult writer. But his ability to write with clarity and simplicity is refreshing. His prose is concrete, and I find I have something solid to grab a hold of, which is especially helpful in his secondary worlds. I see this as a chief characteristic in Pilgrim’s Regress and works like The Great Divorce.

Many American Christians have been exploring or rediscovering the idea of simplicity—limiting tech use, understanding work rhythms, things like that. Can we learn something from how simple Lewis’ writing routine was—using a dip pen instead of a typewriter, pausing to think every few minutes while he refills his ink?

Absolutely. I find much of Lewis’s creative habits helpful and prescriptive. The simple discipline of devoting time to answering letters, his endless devotion to reading, the simple comforts of a pipe or pint, these are all connected to his creative process. I think writing was a simple pleasure for Lewis. He speaks of writing that way. Reading, too. Lewis’s life was quite simple, at least in the facilitation of his creativity.

Any new projects on the horizon?

Yes! I’m finishing, and boy is it overdue, a more popular level, though deep and rich, work on Christian spirituality and creativity. I’m also in the very early stages of putting together a proposal for a book on Psychology According to C. S. Lewis.

Corey Latta’s books can be purchased through all major book retailers.