BY G. CONNOR SALTER

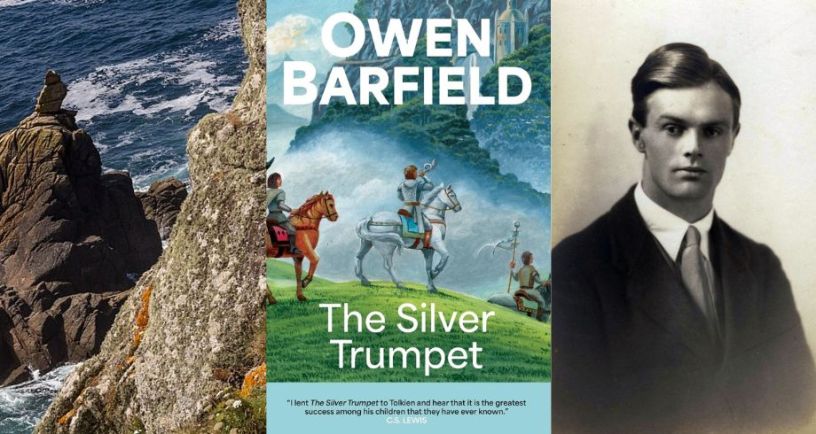

The Silver Trumpet by Owen Barfield. Barfield Press, May 29, 2025. Paperback, 172 pages.

If most readers were asked which member of the Inklings first published a fantasy novel, they would probably answer J.R.R. Tolkien (The Hobbit appeared in 1937). In fact, the correct answer is Owen Barfield, C.S. Lewis’ Oxford classmate credited with helping Lewis overcome atheism. Barfield had an underdiscussed influence on the other Inklings as well: Verlyn Flieger discusses in her classic study Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World how Barfield’s theories about language informed the development of Middle-earth. Barfield’s first work of fiction, The Silver Trumpet, was released in 1925 to good reviews, including positive recommendations from Tolkien’s children when he read it to them. Hard to find for decades, Barfield’s literary estate has published a centenary edition, including new illustrations by Fredy Jaramillo Serna.

Since The Silver Trumpet was published two years after Barfield joined the Anthroposophical Society and twenty-four years before Barfield was baptized into the Anglican Church, it would be tempting to treat this as a pre-Christian fairytale. Barfield argued throughout his life that his spiritual interests in the 1920s were compatible with his later faith, and whatever readers may think of Anthroposophy’s more unusual ideas, nothing in The Silver Trumpet seriously goes outside a Christian worldview. The story offers compelling lessons about deception, jealousy, the nature of wonder, and the poisonousness of cynicism. Without being as explicitly Christian as some scenes that Lewis offers in the Chronicles of Narnia, the book is clearly written by an author immersed in spiritual discussions about the nature of truth and reality.

The story follows twin princesses, Violetta and Gambeta, who appear very much alike but have very different ideas about what matters. A magic spell at their christening ensures that they have intertwined destinies, which keeps them emotionally connected. The connection also makes things complicated when a visiting prince with a silver trumpet falls in love with Violetta. Strange dark magic infects Violetta after she marries and becomes a mother, and soon begins affecting her husband as well. Her daughter will need help from many friends and learn some hard lessons about courage if she’s going to unwind the dark enchantments and rescue her kingdom.

Reading Barfield’s fiction is always curious because he seemed to explore whatever genre came to his mind. His books range from dystopian sci-fi (Night Operation) to philosophical comedy (This Ever Diverse Pair) to ecology-themed thriller (Eager Spring). Given Barfield’s experimentation with different forms, it’s not surprising that The Silver Trumpet is an inventive story. It swings from fairytale to slapstick comedy to gothic drama, then back to fairytale again. Like some of Tolkien’s shorter fiction (especially Farmer Giles of Ham), it reads like the author is bursting with ideas.

While several plot points and set pieces resemble ideas that Barfield’s friends explored in their fantasy stories, the clearest connection it has with the Inklings is mutual influence: The Silver Trumpet owes a great deal to George MacDonald. In fact, Barfield’s opening scene parallels the first chapter of McDonald’s fairy tale The Light Princess so closely it reads like an intentional homage.

Like many of McDonald’s stories, the first act of Barfield’s story emphasizes comedy before giving way to something darker, more ruminative, filled with philosophical overtones. Barfield understands, as MacDonald did, that a good fairytale has to feature darkness as well as light. There are some heartbreaking moments as Barfield’s heroes face their own fears. The writing style doesn’t exude the gothic style MacDonald offers in Lilith, but Barfield offers a compelling villain who is as clever and grotesque as any of MacDonald’s witches.

If the many elements (the comedy, the gothic, the fantastic) seem like too much, the combination offers a particular advantage. As the story develops, as deceptions mount on top of each other and then get upended in unexpected ways, the tonal shifts mean Barfield can offer wilder plot twists than a conventional fantasy novel might allow. By the story’s end, he offers some surprises that even go beyond the twists that readers find in Lewis, Tolkien, or MacDonald.

Barfield’s writing may not have achieved the sales of his friends’ books, but he shows here that he was just as creative. The Silver Trumpet is a memorable fairytale that continues to entertain a hundred years later.

A wonderful book for children or fans of classic fairytales, particularly readers who enjoyed The Hobbit, The Princess and the Goblin, or the Chronicles of Narnia.

For an F&F interview with Barfield scholar Landon Loftin, read: