BY G. CONNOR SALTER

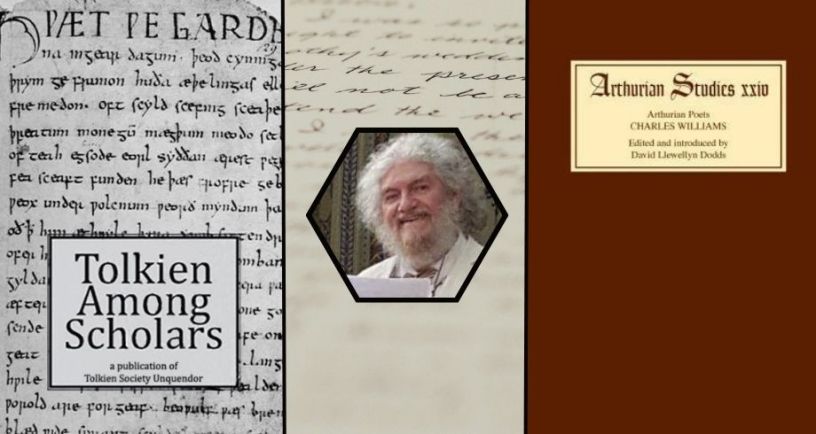

David Llewellyn Dodds studied at the University of Oxford (Merton College) and has the distinction of doing critical work on three of the Inklings. He helped to lead the Oxford C.S. Lewis Society and curated The Kilns, C.S. Lewis’ Oxford home, when it was being restored in the 1990s to become a guest house for visiting scholars. He has edited Arthurian poetry collections of Charles Williams’ and John Masefield’s works, and has contributed introductory articles on Williams to such websites such as A Pilgrim in Narnia and The Oddest Inkling. Dodd’s work on J.R.R. Tolkien, including essays published in Beyond Bree and Lembas, has often addressed unusual topics, from Tolkien’s interest in Magyar to how the hobbits conduct funerals.[1]

He was kind enough to answer a few questions about his Tolkien scholarship and his memories from the early days of Lord of the Rings fandom.

How did you discover Tolkien’s works?

As far as I can recall, my first encounter with Tolkien was “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” in The Beowulf Poet: A Collection of Critical Essays (1968) edited by Donald K. Fry—which I thoroughly enjoyed. And my first encounter with Beowulf was Burton Raffel’s translation (1963). But when? When I had a high school class in Old and Middle English poetry in translation in the early 1970s? My Dad had a copy of the 1965 Ballantine Hobbit from a colleague, and said he enjoyed it, but without adding details—and I was put off, somehow, by Barbara Remington’s emus and whatnot on the cover, and never tried it.[2]

By contrast, in junior high, I had gotten interested in Lovecraft and his circle, and Arthur Machen, and Algernon Blackwood, which led to other books in Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series, including Lin Carter’s Golden Cities, Far (1970), which has an extract from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso—with his sea-monsterish Orc. I had an Italian friend who was keen on Tolkien and she was talking about his Orcs, and I asked if they were like Ariosto’s. She persuaded me to find out how different they were for myself, and lent me her copies of the three volumes of The Lord of the Rings. So I started with our Hobbit and followed up with her loan—and never looked back. This was in 1975.

Was there a point where you developed from someone who read Tolkien to studying his work as a scholar?

Once I started reading him, I wanted to read lots. Most of my early Tolkien books are in storage at the moment, but I see I got my copy of the Ballantine Tolkien Reader (1966)—a wonderfully varied volume, with an introductory essay by Peter S. Beagle—on 17 May 1976. I had the good fortune to be spending a term abroad at Harlaxton College outside Grantham when The Silmarillion came out in September 1977, and I went down to London to Allen & Unwin and bought several copies for myself and some friends—and a copy of Humphrey Carpenter’s biography, which had come out in May.[3]

We had a field trip to Oxford and I found out Humphrey’s address and turned up at his door to get it autographed. He took a break from his home improvements to give me tea and we talked about my interest in Charles Williams—and he told me he was working on The Inklings. Little did either of us know he would be supervising me on Williams a couple years after that.[4]

But, daring to write about Tolkien myself? That only came with the Tolkien birth centenary in 1992, when I followed up my paper for the 1986 Williams Inklings Gesellschaft centenary conference with one on Williams and Tolkien for their Tolkien conference. By January 1992, Christopher Tolkien had published Unfinished Tales (1980) and nine volumes of The History of Middle-earth—with six of those since August 1986. Sadly, I had not kept up my attentive buying and reading of new Tolkien works as they appeared—and so I had a lot of catching up to do if I wanted to be anything like a scholar of his work. (Happily, my future wife did a much better job of keeping up, but even she did not catch every book as it appeared, so we have had belatedly to fill the gaps—and it has taken me years to read [almost] everything in book form at least once.) My first “purely” Tolkien paper was a kind of complementary work to the one on Tolkien and Williams and magic, among other things, expanding attention to his thoughts on “magic” and “the Machine.”[5]

You’ve written extensively about one of Tolkien’s fellow Inklings, Charles Williams. Did you discover their works in isolation of each other, or because they were both in the Inklings?

In isolation—with Williams’s Arthurian poetry, a little earlier. Though one of the first things I read about Tolkien was Lin Carter’s Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings (1969), and it includes a couple of vivid bits about their acquaintance as fellow Inklings, so that may have been my first link. I ended up reading my first Tolkien, Williams, and Lewis fiction at about the same time.

For the benefit of those who do not know the full story, how did Williams come to know Tolkien?

If we can go by Lewis’s first letter to Williams, which arrived on 12 March 1936—and seems to survive only in a transcription made on Williams’s OUP typewriter—the first acquaintance came when Lewis “put Tolkien (the Professor of Anglo-Saxon and a papist)” on to reading Williams’s novel, The Place of the Lion—somethinghe had already mentioned to R.W. Chapman on 9 March.[6] With both Tolkien and Williams being well acquainted with Kenneth Sisam and Chapman, one might think they would have heard of each other sooner, but I know of no evidence of that.

As to personal acquaintance, the next clue is tantalizing: Williams wrote his friend Olive Willis that on 18 May he was “going to Oxford to meet a Don who admires me, in fact, two”—about which Williams’s biographer, Grevel Lindop, notes “The other ‘Don’ was probably Tolkien, possibly [Neville] Coghill”—who was already a fan of Williams’s novels, as Lewis notes in his first letter.[7] The first documented Inklings meeting Don King notes in his splendid chronology where both Tolkien and Williams were present is on All Souls—2 November 1939.[8] Since Williams had been evacuated to Oxford with other London OUP staff on 4 September, the day after Britain declared war on Nazi Germany, Tolkien and he may well have already been meeting regularly—and cordially—as Inklings for weeks by 2 November, but we do not know for sure.

There seems to be a broadly held assumption that Tolkien and Williams did not get along, partly because Tolkien downplayed their friendship in some of his later letters and he allegedly referred to Williams as “that witch doctor” in a conversation.[9] Is there more nuance to their friendship than we assume?

There certainly is, if we go by Tolkien’s published letters—especially with reference to Inklings meetings—written from 28 July 1943 to 15 May 1945, the day of Williams’s death when he wrote immediately to his widow that “in the (far too brief) years since I first met him I had grown to admire and love your husband deeply, and am more grieved than I can express.”[10] A good example is Tolkien writing to his son Christopher around five months earlier, on 24 December 1944, noting of The Lord of the Rings as far as it was written then that Williams was “reading it all” (one of the first people ever to do that in any form!) and that he “says the great thing is that its centre is not in strife and war and heroism (though they are all understood and depicted) but in freedom, peace, ordinary life, and good liking. Yet he agrees that these very things require the existence of a great world outside the Shire.”[11]

I don’t know if anyone followed up that 1967 “witch doctor” remark, which Carpenter quotes from Paul Drayton, his friend and collaborator on their adaptation of The Hobbit as a musical drama, until I did earlier this year. Something about which I hope to write, soon, but it remains tantalizing.

Unless I’m mistaken, your first essay on Tolkien appeared in 1993, “Technology and Sub-creation: Tolkien’s Alternative to the Dominant Worldview,” and considers how he approaches technology, especially how Tolkien offers a different view than many modern people do today.[12]

It does—though not exclusively. My Dutch review of the fascinating collection, Tolkien among the Theologians, appeared recently—and gets me thinking my first paper might have been subtitled “Tolkien among the Philosophers,” not least in the context of the works of two younger contemporaries I attend to there: Eric Voegelin (1901–85: born on Tolkien’s ninth birthday!), among other things a scholar of mythopoeia and the manipulative construction of “second realities,” and George Grant (1918–88), the Canadian philosopher—and avid Inklings reader—who started his studies in Oxford before World War II and attended the Socratic Club when Lewis was its President and whose future wife and collaborator, Sheila Allen, attended Tolkien’s lectures.[13]

(My essay title plays with those of Grant’s books, Technology and Empire (1969) and Technology and Justice (1986). Terry Barker, author of Continuing Chesterton (2015), and I started an Oxford George Grant Society to complement the C.S. Lewis Society in which we were both very active, and a couple of Grant’s letters to me in this context are published in William Christian’s edition of Grant’s Selected Letters (1996). Christian also stayed with us at The Kilns in the course of researching his 1993 Grant biography.)[14]

Was Tolkien skeptical of new technology, or simply wary of its potential for misuse?

I would say that Tolkien, like Grant, was very wary not only of the potential for misuse, but of the particular dangers of “technologies”—and “technological thinking”—conducing to misuse. Good examples are Tolkien’s writing to Christopher on 9 July 1944 after he “went solo” in his training as an RAF pilot, where he speaks of “the tragedy and despair of all machinery”: “Unlike art which is content to create a new secondary world in the mind, it attempts to actualize desire, and so to create power in the World; and that cannot really be done with any real satisfaction.”[15] Another is his 1956 draft to Joanna De Bortadano—which I would describe as distinguishing between “science” and “technology”—taking the example of “nuclear physics”: “They need not be used at all. If there is any contemporary reference in my story at all it is to what seems the most widespread assumption of our time: that if a thing can be done, it must be done. This seems to me wholly false.”[16]

Tolkien’s views on technological misuse have come up many times in discussions about industrial technology (killing forests, etc.), but we’ve also seen a big increase in digital technology since your essay appeared in 1993. Have any of Tolkien’s ideas informed how you approach the digital world?

To try to use some Tolkien imagery, I think he has given me enough sense of palantíri to know that I am no Aragorn and so try to avoid Pippin’s temptation. But, sadly, which digital “device” in the “Internet of things,” from Roomba to refrigerator—cannot be used as a palantír to scrutinize you when you have no intention of gazing into it yourself? How can the savviest programmer always keep a step ahead, or the hardiest ascetic get far enough “off the grid”? To apply Gandalf’s words: even more sharply than in the Third Age of Middle-earth, we need to be “saved […] mainly by good fortune, as it is called.”[17]

Several of your recent articles have dealt with spirituality in Middle-earth, such as what worship looks like and how the created beings relate to the creator (Eru).[18] What were some things you found that surprised you as you studied how Tolkien portrays religion in his works?

With respect to worship, both in Númenor itself and in Númenórean Middle-earth, I was pleasantly surprised at how much detailed evidence there was to be drawn together from works Christopher published after his father’s death and from The Nature of Middle-earth (2021) edited by Carl Hostetter, and how finely it passed by often very subtle hints in The Lord of the Rings— though there is much that remains tantalizing.

Where the relation of created beings and the Creator, Eru, are concerned, I remember having a fascinating conversation with Charles Huttar a number of years ago about the Ainur, Valar, Maiar, and Istari in Tolkien’s work, and the “Angelicals” in Williams’s The Place of the Lion, and the Oyéresu and eldila in Lewis’s Ransom books, and their relations to Biblical angels—a “matter” which has continued to attract me.[19] There is a passage in chapter 16 of Perelandra where Ransom, hearing from Perelandra herself of her planet-building and -ruling work as Oyarsa, refers to what “one of Maleldil’s sayers has told us,” in a clear allusion to St. Paul in the Epistle to the Galatians 4:1-9 where he speaks of the stoicheia (in the original Greek, translated as elementi in Latin, “elements” in the Authorized/King James Version). I think one of the first reviewers of Williams’s novel is right to speak of “the elementary powers” there, too.

And the more widely and carefully I read Tolkien—especially the versions of the Elvish account of the creation told them by the chief of the Valar—the more I am somewhat surprised to find myself inclined to think the Ainur and Maiar are distinct from “angels” and seem like Tolkien’s own “supposal” (to use Lewis’s term) of what the Biblical stoicheia might be like.

Tolkien famously wrote that he deliberately tried to keep his religious views implicit in The Lord of the Rings by removing references to religious activity. He seems to engage more explicitly with religious ideas in his other writings, as he offers a cosmology and creation story for Middle-earth. Does reading the larger story enrich how we see faith being explored in the trilogy?

Absolutely! I have been steadily impressed by how much more this is the case than even I expected. We can’t tell just how he would have presented what we may (by way of shorthand) call the “Silmarillion material” had he lived to prepare it for publication himself, but it is certain that he always intended for there to be a public form so that it and The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings would complement each other.

Of course, Tolkien is writing and revising as mythopoet himself, but I have also been impressed by his growing presentation of himself as a translator and scholar of existing works, with attention to the questions “How did these works reach the form they have?” and “What are the implications?” Tolkien on Chaucer: 1913–1959 helps us see how this echoes his own academic work.[20] Who are the faithful Valar and Maiar? What did they know, and how did they share it, and what did Elves make of what they received—and passed on to Men? So, for example, Tolkien “finds” Finrod in the Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth having inklings of the Holy Trinity from what he has heard of Eru and the Secret Fire.

Several of your works have appeared in Dutch Tolkien scholarship publications, and I believe your Beyond Bree collaborator Viktória Marácz studied in the Netherlands.[21] How did you become connected to this particular circle of Tolkien scholars?

At the 1986 Charles Williams Society birth centenary memorial service in Oxford, we were encouraged to be hospitable to our Dutch visitors, three young women friends from the Dutch Tolkien Society, two of whom were also attending the Tolkien Society Oxonmoot the same weekend. I became friends with them all—and the one who had not booked for the Oxonmoot (as she did not know if she could get off work till the last minute) and I ended up getting married, and living in the Netherlands for the greater part of every year. Then, a couple years ago, I read a Dutch book about Hungarian history and culture which fed into my growing interest in Tolkien and matters Hungarian, and wrote to the author and asked one thing and another, and he put me in touch with Viktória, who is a scholar of both English and Celtic literature, history, and culture— (and a Tolkien fan) living here, who is also fluent in Magyar.

Do you find that European Tolkien scholars focus on different questions than Anglo-American Tolkien scholars explore?

I think there is a comparably wide and varied spectrum of particular interests among European and Anglo-American Tolkien scholars—though, given Tolkien’s breadth of interests in languages, native speakers of Welsh, or Irish, or Finnish, or Magyar, or Spanish, or Italian, or German, to take seven examples, who are also fluent in English, will have distinct advantages in elucidating his interest in their respective languages—as, I think, does Ryszard Derdziński in researching Tolkien’s Prussian ancestry.[22]

Any upcoming Tolkien publications that you can discuss?

Yes, though they are variously works in progress—or in aspiration and planning. For instance, the hinted sequel to my Sven Hedin article, about Tolkien’s “rangers” and Kipling’s Kim and the “Great Game.”[23] And a note about Alcuin’s Lives of St. Willibrord and St. Martin and both Eärendil and the breaking of rings. And revising further articles about Tolkien and matters Hungarian, one comparing the treatments of the Atlantis legend by Tolkien and Mór Jókai (1824–1904, and reported to number Queen Victoria among his admirers), another comparing an incident in the life of St. Ladislas and Éowyn and Merry’s defeat of the Witch-King, and a third, more broadly, on statuary often associated with the Cumans (with lots of examples in the Wikipedia article of that name) and Tolkien’s “Púkel-men.”

I had an exhilarating time writing a fairly extensive overview of Tolkien and the Old English poet, Cynewulf, originally intended as a chapter of Jane Beal’s memorial Festschrift for Richard C. West, “J.R.R. Tolkien and Medieval Poets,” in book form, which (alas!) I decided not to publish in the special-issue version in the Journal of Tolkien Research when I had carefully read all their—to my mind, hair-raising!—Terms and Conditions.[24] I have not yet found another publisher for it as a whole, and am in any case revising sections for separate publication, such as the one on Tolkien’s second verse-riddle written in Old English (for Beyond Bree).

Working on that overview intensified my interest in Tolkien’s “contrafacta,” his writing of new words—sometimes in Old English!—to existing tunes, which has already borne some published fruit in my Lembas Extra 2024 paper with respect to “Over Old Hills and Far Away,” but I hope to write more about them, whether the 13 words in Songs for the Philologists or others elsewhere.

What are some topics you would like to see more Tolkien scholars explore?

I may not be a very good person to ask, given how difficult I find it to keep up with “the literature.” Specifically, I would rejoice to see Patrick H. Wynne’s work on Tolkien’s Magyar-related Mágo/Mágol texts appear, and Carl Hostetter produce something about Tolkien’s annotations in his copy of József Szinnyei’s Ungarische Sprachlehre (1912).

And John Bowers was variously helpful in my work on Cynewulf, and told me that his conclusion on examining Tolkien’s lecture series among the manuscripts in the Bodleian Library on Cynewulf’s poem Elene—about St. Helena and the discovery of the Cross—was that the material deserved editing and publishing. Such an edition is something else I would rejoice to see.

Tolkien on Chaucer includes various interesting examples of Tolkien writing on the lives of saints. And Jane Beal published an article in 2020 entitled “Saint Galadriel?: Tolkien as the Hagiographer of Middle-earth.”[25] Not unrelated to this is Tolkien’s own reference to the importance of 25 March in his “Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings” (published as long ago as 1975 in the first edition of Jarrod Lobdell’s A Tolkien Compass) which could be seen as giving a strong accent to the matter of “typology” in his legendarium—something both Dale Nelson and I have also written about, but which invites more judicious attention, however speculative.[26] For example, in my Lembas Extra 2022 paper, I note Gandalf telling the rescued Frodo in Rivendell “It is the morning of October twenty-fourth” is referring to a date that (in its Gregorian calendar equivalent) some 9200 years later (by a decree of 21 October 1921) will be made the Feast of St. Raphael the Archangel, of whom Gandalf in his degree seems a type.[27]

Of course, Claudio Testi’s lively and fascinating Pagan Saints in Middle-earth appeared in its English version in 2018, inspired in part by Jean Daniélou’s Les Saints « païens » de l’Ancien Testament (1956).[28] There is some pointed friendly fencing between Testi’s main text and Tom Shippey’s “Afterword” about the significance of 25 March, and I think Testi should have improved on Daniélou’s Italian and English translators by preserving his playful quotation marks around “Pagan.” But a lot remains to be said—and discovered—about Tolkien and saints (angelic and human—and imagined, among other “peoples of Middle-earth”) and typology.

Where can people find your past work on Tolkien?

While I had published a couple reviews in The Charles Williams Society Newsletter/Quarterly and one in Mythlore (most now accessible online) and another in the Church Times, in recent years I have done a lot more reviewing, with increasing frequency of books by and about Tolkien, though also ones about Charles Williams, and the Inklings, and by Dorothy L. Sayers. A number of these are freely accessible in the online versions of VII: Journal of the Marion E. Wade Center.[29] About half of my reviewing is in Dutch for Lembas, the journal of Unquendor: The Dutch Tolkien Society, but I write English versions of these for the convenience of the publishers, and I think Walking Tree Publishers has taken to posting some on their website, while the one of Holly Ordway’s Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography appeared in the May 2025 issue of Beyond Bree (2–4).

Worth adding is my second “purely” Tolkien paper—which my old high school history teacher and lifelong friend advised me would be judicious to leave out of my Curriculum vitae on account of its less-than-self-explanatory title: “The Centrality of Sex in Middle-earth,” Lembas Extra 1993/1994 (my second appearance with Tom Shippey in a collection!). It attends both to Tolkien’s masterful stylistic subtlety in the handling of his tale of the Children of Húrin in comparison with that of Kullervo in the Kalevala, and the analogous tales in the Volsunga Saga, the Niebelungenlied, and Wagner’s Die Walküre; and to the typological aspect of Tolkien’s mythopoeic choices with respect to his emphases on sexual reproduction in contrast, for example, to Wells imagining his Martians to be “absolutely without sex” in The War of the Worlds. I think Tolkien’s eye is on St. Luke 1:31 and the wonders of Incarnation.

[1] For Beyond Bree contributions solely written by David Llewellyn Dodds, see: “‘Kubla Khan’, Doctor Doolittle, and Father Nicholas Christmas?” (December 2020): 1–3; “C.W. Stubbs and J.R.R. Tolkien: Possible, Plausible Connections and Intriguing Comparisons” (August 2021): 4–7; “Tolkien, Freeman, and Golom?” (April 2024): 6; “The Inklings Century #3: How a London Novelist at the OUP Joined the Inklings: Part 1” (July 2024): 4–5; “The Inklings Century #3: How a London Novelist at the OUP Joined the Inklings: Pt. 2” (August 2024): 3–5; “Tolkien’s Guest Gwyn Jones” (December 2024): 5–6.

[2] Various fans, and Tolkien himself, have questioned the use of emus and a fruit tree on this cover by Barbara Remington. For example, see Brian Sibley, “Hobbits and Lions and Emus, Oh My!” Blogger.com, 18 April 2017, https://briansibleysblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/hobbits-and-lions-and-emus-oh-my.html. See Tolkien’s disapproving letter to Ballantine in Letter 277, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded, ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien (Allen & Unwin, 2023), 506.

[3] J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography was first published in May 1977, the first of three books on Inklings topics (the first Tolkien biography, the first book on the Inklings, the official collection of Tolkien’s letters) and one booklet (The Lord of the Rings Souvenir Booklet released in 1980) published by Carpenter.

[4] Humphrey Carpenter served as one of the supervisors on a Bachelor of Literature thesis that Dodds wrote at Merton College, Oxford, through a Rhodes Scholarship.

[5] “Technology and Sub-creation: Tolkien’s Alternative to the Dominant Worldview.” Scholarship & Fantasy: Proceedings of The Tolkien Phenomenon edited by K.J. Battarbee (University of Turku, 1993), 165–185. For the Tolkien and Williams article discussing magic, see David Llewellyn Dodds, “Magic in the Myths of J.R.R. Tolkien and Charles Williams,” published among the Centenary Symposium papers in Inkling Jahrbuch vol. 10 (1992): 37–60.

[6] See letter dated 11 March 1936, The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Volume 2: Books, Broadcasts, and the War, 1931-1949, ed. Walter Hooper (HarperCollins, 2004), 183. See also Grevel Lindop, Charles Williams: The Third Inkling (Oxford University Press, 2015), 256.

[7] Lindop, Charles Williams, 259.

[8] See Don W. King, “When Did the Inklings Meet? A Chronological Survey of their Gatherings: 1933–1954,” Journal of Inklings Studies, vol. 10, no. 2 (2020): 184–204. https://doi.org/10.3366/ink.2020.0079. For interviews with King published in Fellowship & Fairydust, see https://fellowdustmag.com/?s=don+w.+king.

[9] See Humphrey Carpenter, The Inklings (Allen & Unwin, 1979), 121, 272.

[10] See Letter 99 in Carpenter, Letters, 167.

[11] See Letter 95 in Carpenter, Letters, 151.

[12] See David Llewellyn Dodds, “Technology and Sub-creation: Tolkien’s Alternative to the Dominant Worldview.” Scholarship & Fantasy: Proceedings of The Tolkien Phenomenon ed. K.J. Battarbee (University of Turku, 1993), 165–185; see also Dodds, “‘Tolkien’s Narnia’? Lit., Lang., Saints, Tinfang, and a Mythology – or two – for Christmas,” Tolkien Among Scholars: Lembas Extra 2016 ed. N. Kuijpers, R. Vink, and C. van Zon (Tolkien Genootschap Unquendor, 2016), 85–103.

[13] See David Llewellyn Dodds’ contributions to Lembas and Lembas Extras, available at Tolkien Genootschap Unquendor, https://www.unquendor.nl/.

[14] See William Christian, George Grant: A Biography (University of Toronto Press, 1993).

[15] See Letter 75 in Carpenter, Letters, 125.

[16] See Letter 186 in Carpenter, Letters, 35–354. Dodds noted that the 2023 edition does not capitalize “De Bartadano.” It is capitalized on Tolkien Gateway.

[17] See J.R.R. Tolkien: The Two Towers (Allen & Unwin, 1954), 199. In the book’s context, good fortune is implied to be divine grace.

[18] David Llewellyn Dodds, “‘Not his to worship the great Artefact’: Loving and Misloving the Creature, Making and Falling among the Ainur, in Eä, and throughout the Life of ‘Man, Sub-creator,’” Evil in Eä: Lembas Extra 2024 ed. J. van Breda, C. Marchetti, J. Steen Redeker, and R. Vink (Tolkien Genootschap Unquendor, 2024), 155–72.

[19] For more on this topic, see Charles A. Huttar, “How Much Does That Hideous Strength Owe to Charles Williams?” Sehnsucht: The C.S. Lewis Journal, vol. 9, no. 1 (2015): 19–46. https://doi.org/10.55221/1940-5537.1321.

[20] See John M. Bowers and Peter Steffensen, Tolkien on Chaucer: 1913–1959 (Oxford University Press, 2024).

[21] For their Beyond Bree articles written together, see David Llewellyn Dodds and Viktória Marácz, “Tolkien and Magyar – and Other Matter Hungarian?: A Preliminary Inquiry: Part 1” (May 2024): 1–5; “Hungarian as a Dream Language in The Notion Club Papers” (June 2024): 1–4.

[22] For more on Derdziński’s work as a translator and illustrator, see https://tolkniety.blogspot.com/.

[23] See David Llewellyn Dodds, “Sven Hedin—and The Hobbit?” Beyond Bree (May 2023): 4–5.

[24] For this issue, see Journal of Tolkien Research vol. 19, no. 3, “J.R.R. Tolkien and Medieval Poets,” in honor of Richard C. West. https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol19/iss3/.

[25] See Janet Beal, “Saint Galadriel?: J.R.R. Tolkien as the Hagiographer of Middle-earth,” Journal of Tolkien Research, vol. 10, no. 2 (2020): 1–35, https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss2/2.

[26] For examples, see Dale Nelson, “Contemplated But Not Resolved: Opening Up Lear and Lord of the Rings.” Portable Storage no. 6 (2021): 30–41; for Beyond Bree articles co-written by Dodd and Nelson, see “Thélemè and Sæmund: Two Source Speculations for The Treason of Isengard” (November 2020): 5-6; “What Were the Funerary Customs of the Shire-Hobbits?” (June 2022): 4–5; “Inklings Century #1: The Morbid Twilight of These Days” (April 2024): 2–4.

[27] “Faithful Cultus in Númenor and Númenórean Middle-earth,” Númenor: Lembas Extra 2022 ed. J. van Breda and R. Vink, (Tolkien Genootschap Unquendor, 2022), 131–150.

[28] Claudio Testi, Pagan Saints in Middle-earth (Walking Tree Publishers, 2018).

[29] See VII issues available to read online, see https://www.jstor.org/journal/seven. For digitized Charles Williams Society Newsletter/Quarterly reviews, see https://www.charleswilliamssociety.org.uk/. For Mythlore reviews, see https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/.