BY LYNNE BASHAM TAGAWA

Boston. December 1770.

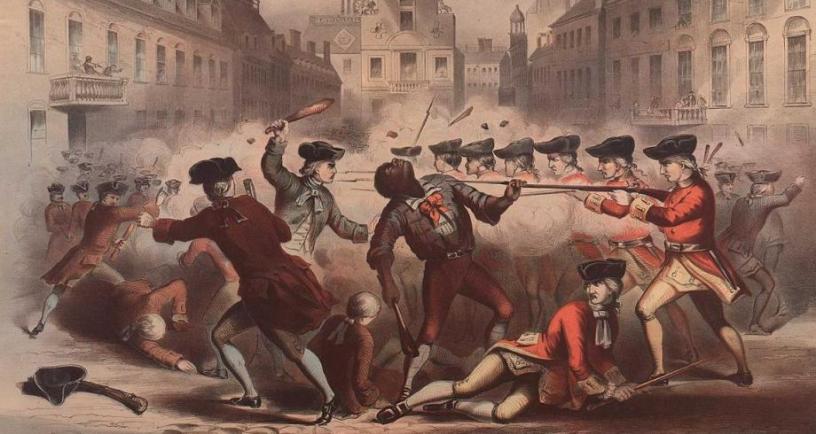

A clod of manure flew through the air and impacted the red brick of the courthouse.

Abigail Adams stopped in her tracks. Too close. Behind her, John’s white wig shone in the morning sunlight, his black robe still folded under his arm. Her sister’s husband, Richard, turned and addressed the crowd.

“Behave ye like civil men!” Richard bellowed.

Abigail almost smiled. Richard was slender, his long fingers better suited for exploring the intricacies of a clock than for fighting. But he stood straight, jaw clenched. He was no coward.

“Hang the lobsterbacks!”

John stopped, motioning them to continue inside.

“Adams is a traitor!”

She placed a foot on the first step, then scanned the scowling crowd. A few faces were friendly. Perhaps not all of Boston hated the Adams family. Carriages thronged the road; not everyone would make it inside on this eventful day.

Another missile flew past them. John gestured to the crowd.

“Does not every man deserve a fair trial?”

She took a deep breath and entered the building, Richard just behind her. The clunk of a closing door marked John’s entrance. He detoured to the judges’ chamber while Abigail and Richard made their way to the second floor amid a stream of last-minute attendees like herself who had reason—and permission—to enter the room.

She’d been here before, for Captain Preston’s trial. Now, the second half of the drama would conclude, the trial of the rank and file who had fired upon the crowd that horrible March evening. Light from tall windows illuminated the high-ceilinged space, packed with bodies. She gripped one side of her best skirt and made her way to the seat reserved for her as the wife of the defense counsel.

To one side, the jury sat on their benches. On the other, the defendants stood at the dock, dirty uniforms below scruffy faces. Above, tradesmen in brown wool stood in the gallery. More prosperous Bostonians occupied seats below them.

Some were her own family. The Boylstons in expensive, colorful silk stood out. Two of her Quincy relations were closely involved in the trial: Samuel Quincy was a prosecuting attorney, while his brother Josiah served as John’s assistant. Other prominent Bostonians were in attendance, like Dr. Joseph Warren, well-dressed as usual, lace protruding from his sleeves. She looked for Henry Knox, the garrulous young bookstore owner, but did not see him. But then, he’d given his testimony already.

Some of the expressions of the attendees were hostile, like the men outside, but the faces of others seemed patient.

Dr. Joseph Warren was a member of the Sons of Liberty and no friend to the occupying troops. But his face looked calm. An intelligent, thoughtful man. Would to God all Bostonians were as sensible as he.

John took his seat at his place, his black robe fluttering. Abigail’s heart raced seeing him. She knew he’d prepared. She had all faith in his ability to argue a case. But the hysteria that had followed the Boston Massacre had not vanished. The trial of the Redcoats had been pushed to the fall to give them a semblance of fairness, but anger still lingered like a miasma.

Her heart returned home to her children. They were so young, Charles just a babe. Mother disliked the twelve-mile drive to Boston but proclaimed herself capable of managing little ones. These families, now intertwined—Adamses, Boylstons, Quincys, Smiths—were like a strong multi-stranded rope, even if a certain Quincy sat on the other side of the courtroom. But Abigail feared for the future. The future in which her children would grow up. The Stamp Act, the Intolerable Acts… they were the winds of a storm. But this event, and this trial, was a nexus, like the eye of a hurricane.

Abigail had not been in Boston that fateful March day but only heard of the events from others the next afternoon.

She’d heard a knock.

“Mistress Adams.” The neighbor’s lad told her the tale of ringing bells, crazed soldiers, and blood on the snow. The details, the causes, were sparse, but came to light over time.

None of it surprised her.

“All rise.”

She shook away the past and focused on the courtroom. Everyone stood to acknowledge the entrance of the judges, clad in brilliant crimson, clean and sweeping, unlike the filthy defendants. Even Captain Preston, standing with his men, showed the effects of long imprisonment. His officer’s gorget was missing, and he wore no wig.

For once, the sight of the red coats did nothing to stir Abigail’s animosity. She sat with the rest and smoothed her skirts, breathing a silent prayer for her husband.

Lord, thou knowest…

God knew what John needed. And God knew the mood of Boston, a dank cloud that hovered over all of Massachusetts. She was a proponent of liberty as much as anyone, but not liberty at the expense of justice.

It had been a long year. First, a snowy March evening, branded on all their memories. Then, in September, the beloved minister George Whitefield died the morning after his last sermon, and his body buried in Newburyport. Then, just six weeks ago, Captain Preston had been cleared of the charge of murder but not of suspicion. Boston still hung on the edge of riot.

His men stood in the dock now, their eyes downcast. Once, one of the men looked up at the defense’s table where John sat. Was there hope in his face?

Taking the job had been an easy choice for her husband. No one in Boston understood, except perhaps the family, and John felt the barbs sent his way; she knew. But he couldn’t decline the case.

No one else would defend these men.

But Abigail shared her husband’s conviction that every man deserved the right to counsel and a fair trial.

Samuel Quincy, the prosecuting attorney, rose first at the command of the presiding judge. He interviewed a witness and made it sound as if the discharge of the soldiers’ weapons was an act of utmost perfidy.

“Snowballs!” he said. “Why should a man-at-arms kill a lad who threw a snowball at him?”

It wasn’t an accurate description of the night on King’s Street at all. But her cousin was doing his best to prosecute, and Abigail was suddenly glad he was better at wills and estate matters than murder trials.

John sat listening, looking at his notes, seemingly unperturbed. His mind must be churning as it always did. Was he reviewing a certain Italian criminologist’s words even now, as he had rehearsed them to her?

“If, by supporting the rights of mankind, and of invincible truth, I shall contribute to save from the agonies of death one unfortunate victim of tyranny, or of ignorance, equally fatal…”

The Crown was engaged in tyranny against the colonies. But God forbid the citizens of Boston engage in the same.

Her cousin closed his case, and her husband stepped up to the witness.

“Snowballs. Did they throw anything else?”

The witness stumbled in his words. “Perhaps,” he concluded.

John strode down the line of spectators and then to the jury, his black robe giving him a magisterial air. Then he turned. “Might they have carried clubs?”

“Yes. Yes, they carried clubs.”

The room grew tight with tension.

“Every man has the right to self-defense. Even soldiers.” Her husband looked about the room, as if concerned that everyone, rich or poor, should understand his reasoning. “We need to know what happened that fateful evening.” He turned toward the soldiers; their eyes locked on him. “We need to know who or what is truly responsible for this tragedy.”

Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, Crispus Attucks, and Patrick Carr. All dead. Patrick Carr had suffered for days.

“I call as witness, James Goodall.”

A tradesman sitting near the Boylstuns lifted his hand timidly. “I am here.”

“Tell me, Mr. Goodall, what you saw the night of March fifth, before the Customs House.”

“I saw one soldier knocked down. His gun fell from him.” Goodall swallowed. “I saw a great many sticks and pieces of sticks and ice thrown at the soldiers. The soldier who was knocked down took up his gun and fired directly.”

“Thank you.” John spoke to the jury. “We have eyewitness testimony that the soldiers were attacked.” He lifted his gaze to the scowling gallery. Then said, “I call as witness, Dr. John Jeffries.”

The physician made his way forward. “I am he.”

“Were you at the square, the evening of March fifth?’ John asked.

“I was not.” Dr. Jeffries shifted the tricorne in his hands.

“Did you treat one of those injured in the melee?” John asked.

The doctor nodded. “Patrick Carr.”

“If you would, tell us what Mr. Carr said about what happened that night.”

The physician’s Adam’s apple bobbed. “He said, near as I can recollect, that the soldiers fired in self-defense.”

A murmur rose in the courtroom, then ebbed.

“How did Carr know that?”

“I asked him whether he thought the soldiers would have been hurt if they had not fired,” Dr. Jeffries said. “He said he really thought they would, for he heard many voices cry out, kill them.”

“Imagine this,” John said, walking yet again before the jury. “Kill them, kill them. They were armed with clubs. Who were these people? The best of Boston? No, they were the sailors, the saucy boys, disreputable men. In short, a mob!”

The murmur rose again, the mood electric. Abigail grew warm under her bodice. John’s forehead gleamed below his wig.

John stepped closer to the jury. “You have heard the testimony of all these witnesses.” He proceeded to list several and reminded the jury of their remarks. “Even Captain Preston agrees that the arrival of His Majesty’s troops was extremely obnoxious to the inhabitants. I submit to you,”—he turned and gestured to the spectators—“that the true culprit is a standing army in peacetime!”

He faced the jury once more. “Was there malice in the hearts of these soldiers against the men of Boston? Against Gray, against Maverick? The evidence says no.” He paused. “Facts are stubborn things. And whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictums of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

Abigail looked at the faces of the jury. Twelve men. Most were impassive, but a few were frowning. Were they Boston men? Were some from Charlestown? Cambridge? The country?

One of the judges spoke. “The jury is dismissed to decide the verdict.”

The bailiff cried, “All rise.”

She stood and watched the judges in their fine robes retire.

***

Abigail joined her husband at the defense table once the gallery had emptied. Richard walked over with a bag in his hand.

“Mary sent this.” He opened it to reveal several thick slices of bread, a wedge of cheese, and a jug of cider.

“My sister thinks of everything,” Abigail said, studying her husband.

Now relaxed, lines of strain were visible on John’s face. He was only thirty-five but looked older in that moment. She passed him a handkerchief. He flashed a smile and wiped his face.

“How long do you think the jury will take?” she asked.

John pursed his lips.

“I recognized several of them,” said Richard. “Not from Boston.”

“Is that good?” she asked, guessing that it was. After the shooting before the customs house, Boston had been in an uproar. Putting the soldiers in jail at least kept them safe.

John nodded slightly and passed her the cider. “The longer they take, the better. A mob takes no thought for justice. They are activated by emotion. A thoughtful man considers both sides. If some of these good men live in the countryside, or in Cambridge, or even in our fair Braintree, they may not have been exposed to the crass hysteria in town.”

Richard chuckled. “I wonder what your cousin Sam would say to that description of the mood of Boston.”

John smiled. “Oh, I doubt he would disagree. But Sam is a political animal. He would rather use the energy of a mob for his own purposes than condemn it to no end.”

Abigail had to agree. Still, she liked Samuel Adams. “Richard, tell Mary this is wonderful cider.”

“You saw our orchard. Just purchased a press.”

She listened to the men speak of ordinary things. But the faces of the soldiers nagged her.

“John, what will happen if they are found guilty?”

“If they are found guilty of murder, they will hang.”

Her stomach clenched. Murder. What would happen if a Boston court sentenced the king’s men to death?

The Mother Country already treated them like wayward stepchildren.

The creak of a door interrupted her thoughts. The galleries began to fill with townspeople.

The jury hadn’t been out all that long. Was that good or bad? Either way, these men had settled on a verdict.

The judges filed into the courtroom, their faces impassive. Richard left for his seat, and John fingered his wig before taking his place at the defense table. Abigail returned to her reserved seat. The weather was cool, and the room wasn’t warm, but her skin was sweaty beneath her chemise.

The defendants were escorted inside, and then the jury took their places.

The head judge instructed the clerk, who read the verdict: “Six of the accused are declared innocent.”

Men shifted and stirred in the gallery, and voices rumbled throughout the room until the judge called for silence.

Six—what about the other two?

Movement stilled and faces were tight. A few frowned.

The clerk continued. “Matthew Kilroy and Hugh Montgomery…”

The room froze.

“Are found guilty of manslaughter.”

Abigail could breathe again. Manslaughter. Guilty, but they would escape the noose. She glanced at the defendants. Loosened jaws revealed shock—and relief. One wiped his eyes. Another gazed at her husband with an expression she could only interpret as thankful.

Tears came to her eyes.

Voices rose. Several hostile glances from the gallery flew toward the defendants, but the mood softened and deflated. There would be no violence today.

John found a seat next to her. “What’s wrong?”

“They won’t be hanged.” She wiped her face. “Congratulations, John.”

“They’ll be branded, I’m sure.”

“Seems medieval.”

“It is, in a way.” John watched the spectators leave, some angry, some bemused. “There’s an old legal loophole called ‘benefit of the clergy.’ The defendant prays, and if he is seen as penitent, he is spared. But only once.”

“Only once. So, they brand them?”

“They can’t use that loophole again.”

Richard joined them. “I’ll bring the carriage.”

John took a last look around the courtroom. “One day, I want to retire to my farm and do nothing but make good cider.” He took a breath and gazed into her eyes. “It might be a while.”

“In time, we’ll dwell peacefully under our fig tree.”

The future was hazy, but Abigail didn’t say that. She’d stand by his side till the end.