BY PETE WEBSTER

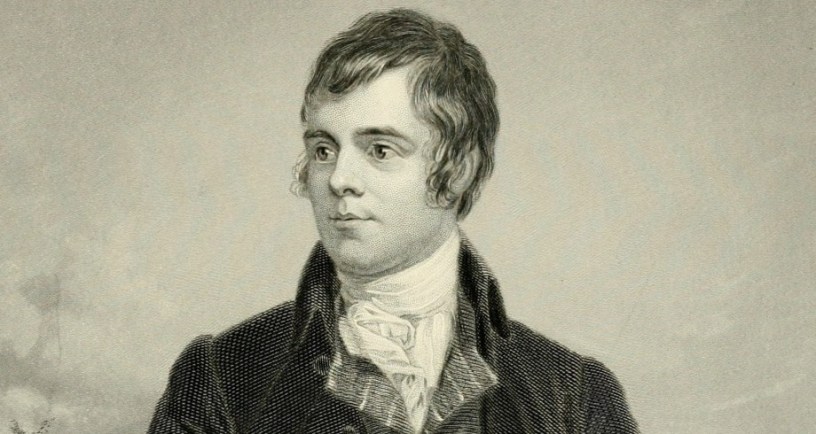

Ladies and gentlemen, let us raise our glasses to the immortal memory of Robert Burns. Though centuries have passed since his pen first touched paper, his words continue to inspire and unite us with their wit, warmth and humanity. Burns, the ploughman poet, gave voice to the hopes and dreams of ordinary folk, and with each verse, he captured the heartbeat of Scotland and the universal spirit of humankind.

Tonight, as we honour his legacy, let us remember his passion for justice, his love for language, and the enduring power of his poetry to bring joy and reflection to people around the world. To Robert Burns—may his memory ever burn bright!

— Microsoft Co-Pilot Toast

A year ago at this dinner, my contribution was to sing “My Love is Like a Red Red Rose.” Perhaps that poem is in a way Rabbie Burns’ own immortal memory. “And I will luve thee still, my Dear, till a’ the seas gang dry.”

Burns’ “Dear” is not identified, nor are her particular fair features described. What we are given is a poet’s expression of Love. And that Love will last until an event which would spell the end of the world and would destroy all human life well before it was complete.

What I want to celebrate and cherish and invite you to toast with me tonight is not something we collectively might remember about Rabbie Burns, but how Rabbie Burns remembered us.

And of course not just us gathered here tonight, but people in many different times and places and stations in life.

It has been said that Burns was a man of contradictions, and the poem that I have offered to sing later tonight seems to contradict “My Love is like a Red Red Rose.” “Ae Fond Kiss and then we sever” is about break-up. No waiting for the seas to dry up and the rocks to melt. “Ae fareweel, alas, forever!”

Burns’ love has a name this time: Nancy. But we learn little more about her than we learn about whoever inspired “My Love is Like a Red Red Rose.” Only that “Naething could resist my Nancy; But to see her was to love her; Love but her, and love forever.”

Love is still immortal. But in this instance it cannot keep two people whose lives are moving in different directions together. They are left broken-hearted, with heart-wrung tears and warring sighs and groans pledged and waged on Burns’ side.

If we are remembering Rabbie Burns through these two poems, we may choose to remember a man who loved and was loved by many women and who could not readily settle down. But if we are the ones who are being remembered in the poems, then we should perhaps instead be looking into the mirror that Burns the poet holds up to us. There is a timelessness, an immortality in the human experience described – as Shakespeare put it in one of his sonnets: “Nor shall Death brag thou wand’rest in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou growest.”

Rabbie Burns has been credited with preserving the Scots language at a time when English language and culture were in the ascendancy. His century had seen the Act of Union and the final defeat of the Jacobites at Culloden. It was a significant and perhaps a brave choice to write in the vernacular.

Yet there are other reasons for a poet to prefer the vernacular over the prevailing literary language of the day. For all his credentials as a ploughman, Burns was an educated man. He was not writing in Scots because he knew nothing else.

I suspect that like Dante Alighieiri before him, who wrote his Divine Comedy in vernacular Italian instead of Latin, Rabbie Burns wanted the “eternal lines” that he was penning to be something ordinary people could read or just hear recited in a language they could understand and identify with, and could memorise and pass on orally as well as in writing.

Love is a universal human experience. Dante explicitly identified it with the divine, and ended his poem in contemplation of the “love that moves the sun and the other stars.” Burns describes love as being “for ever” even when a particular relationship may be interrupted or ended.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is the immortal memory that Rabbie Burns had and still has in the lines of his poems for you and for me.

There will be some here who have cherished Tam O’Shanter and the Address to the Haggis since childhood and can recite them perfectly. To others – perhaps including myself – the language may be opaque but nonetheless dramatic and engaging. Yet for all of us, experiences with food, drink and travel are brought alive in vivid, imaginative and beautifully crafted poetry.

And so it is with love. Life’s best, and worst, experiences are associated with love. Poetry helps us rejoice in life’s best moments and provides solace in life’s worst. Somehow putting the experience into words, metrically organised and maybe set to music, provides a salutary perspective on our triumphs and our disasters, and can turn them into smiles and laughter.

Burns’ century had seen sensibility acquire cult status in high society, especially in France. The century had of course concluded with revolution in that country, hot on the heels of revolution in Britain’s American colonies. People’s feelings were driving seismic social and political change.

And yet…invoking people’s love of their country to take vengeance upon the enemies of freedom comes at a cost. As does any endeavour where others lie perhaps unwittingly in the way. Rabbie Burns highlights the plight of the mouse in the field he has just ploughed:

“Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste,

An’ weary winter comin fast,

An’ cozie here, beneath the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

Till crash! The cruel coulter past

Out thro’ thy cell.”

In solidarity with the mouse he has made homeless he reflects in words that have become immortalised:

“The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!”

But then distinguishing himself from the mouse:

“Still, thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward tho’ I canna see,

I guess an’ fear!”

You might wonder how the poet can proceed from such a premise when he has acknowledged that the mouse saw winter coming fast and made itself a safe underground dwelling away from the cold.

But it’s hard to tie down poetic imagination with rules of logic. The poet’s reflection turns from the mouse to himself. He is not a brute beast of the field with no understanding. Nor are we according to the old prayer book. Our awareness extends back from present calamities to past ones that still affect us and forward to “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns” lying beyond “the whips and scorns of time.”

Again by remembering himself at the end of the poem Burns the poet remembers his readers and listeners including us.

And we in turn may recognise and smile at our own frailty when compared to a “wee, sleeket, cowran, tim’rous beastie.”