BY G. CONNOR SALTER

Karlee Rene Bowlby met her husband, Ewan, in online seminars in 2021, when they were both students at the Institute for Theology, Imagination and the Arts (ITIA) at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. As discussed in a profile for the Telegraph, Ewan had his first seizure at 16 and was diagnosed with a brain tumor at 17, and had a series of brain surgeries over the next decade, receiving a formal cancer diagnosis at 21. He was pursuing a PhD focused on how fictional narratives in popular works of art like novels, TV series, and films can provide emotional and spiritual care for cancer patients by helping them to navigate their stories.

Karlee was studying for a Master’s degree in ITIA, and they both became involved in Transept, a group of creatives associated with ITIA who met weekly to discuss their work. They married in May of 2022, days after Ewan learned that his tumor was not responding to chemotherapy. Ewan passed away in December of that year. Friends remembered him for his involvement with Maggie’s cancer charity and his commitment to the ITIA community, including helping to lead Transept and serving as Editor-in-Chief of the ITIA journal Transpositions.

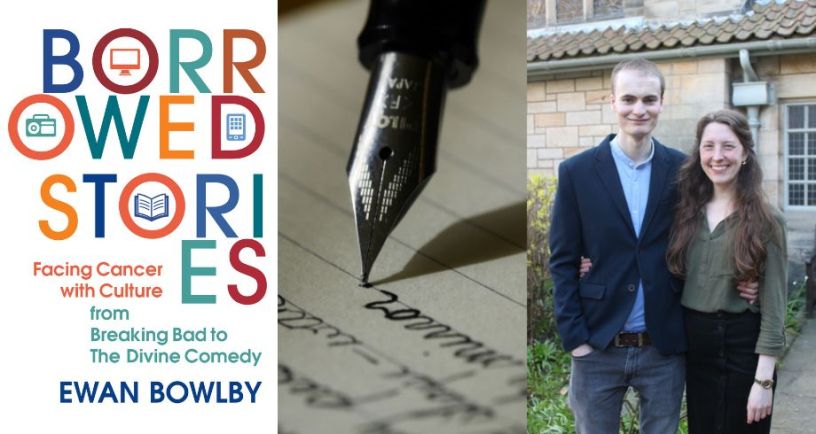

Karlee, now living near St Andrews, helped to edit some of Ewan’s writing, which has been posthumously published as Borrowed Stories: Facing Cancer with Culture – from Breaking Bad to the Divine Comedy. The book was released by Darton, Longman, & Todd in summer 2025, with a foreword by Rowan Williams (who supervised Ewan’s undergraduate dissertation at Cambridge) and an extract released in the Church Times.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS:

For the benefit of those not familiar with your story, how did you meet Ewan?

I first met Ewan as a little square on my computer screen. I entered the ITIA MLitt program in the middle of the pandemic in August 2020. Of course, we were all ignorant of it being the middle of the pandemic at the time, and were hopeful things were improving and that the end was right around the corner. However, that is not how things turned out, and nearly the entirety of my one-year program was online rather than in person. Ewan and I both virtually attended our institute’s weekly research seminars as well as the gatherings of the student art group that we both participated in. We helped to plan an exhibition together, he edited some writing of mine for Transpositions, and we exchanged a handful of emails on subjects of overlapping interest. In spring of 2021, we finally met in real life for a walk along the beach and it was more or less love at first sight.

Did Ewan discuss plans to share his work with a wider audience, or was it more for a family discussion after he had passed?

Ewan always felt passionate about his academic work being available to a wider audience. The initial inspiration for his research was his own experience with fictional narratives as a cancer patient, and his desire to share what he had learned and to improve the lives of real people was always an urgent motivating factor in his work. He put much of his research into practice as a PhD student, designing and implementing several successful cancer patient resources for Maggie’s and the Northumberland Cancer Support Group.

When he knew he was running out of time, Borrowed Stories became a priority for him. He wanted to offer inspiration and encouragement to as many people seeking a more constructive, imaginative relationship with their mortality as possible. Before he had even submitted his doctoral thesis, he began writing the memoir section of the book, planning how he would interweave it with his PhD findings, and sending proposals to potential publishers. Bringing the book to publication after his death was something Ewan’s family felt grateful to be able to complete on his behalf because we knew how important it was to him.

Ewan explored using culture to discuss cancer and help cancer patients in his PhD thesis, “From Beune to Breaking Bad.” How much does Borrowed Stories draw on the thesis, and how much of it is later material?

Ewan had initially planned to write about his own cancer journey at the beginning of the book and then to re-work his thesis into something more readable and interesting to a popular audience. He wanted to weave his personal experiences together with fictional narratives and the stories of friends, family, and fellow patients to show how “borrowing” from other stories helped him to tell his own. These chapters were to focus on the themes of death, time, humor, and relationship following the four main chapters of his thesis. However, he died while writing the memoir section of the book, and left his father with the task of simplifying his PhD thesis so that it would be suitable for a popular audience. Together, his father and I worked with the publisher to edit the memoir and adapted PhD thesis into parts I and II of Borrowed Stories. We took a very light-handed editing approach (mostly just organizing, polishing, and proofreading), so the entire book is Ewan’s words.

While researching Borrowed Stories, I came across some of Ewan’s articles for academic journals, and was struck by his willingness to embrace high culture alongside popular (or “low”) culture. He wrote in Intima and Critical Studies in Television about the educational value of using episodes from Breaking Bad and Orange is the New Black to talk with cancer patients. He wrote in Literature & Theology about how Eugene Vodalazkin uses Johannine theology in his novel Laurus. Were you surprised by any of the cultural references he mentioned?

Yes, he had a remarkable appreciation for both high and low culture. As soon as I got to know him, I wasn’t surprised by his ability to find value and something worthy of consideration in almost any medium that crossed his path. He had a very open and generous approach that fit well within the ITIA community. I loved being able to share the breadth of high and low art that I found moving with him because he always took it so seriously.

You’ve written for the St Andrews alumni page about how Ewan did not consider himself an artist, but was very committed to supporting artists in community through Transept. What are some ways you saw him support others?

That’s right, although I will say that after a few drawing lessons from me, he showed real artistic potential in my opinion. His support for artists was widespread and varied—from using his height to help artists install their work to using his leadership skills to facilitate and guide Transept meetings to using his eloquence to champion art of all kinds through his research and writing. And, of course, there is the support he offered to the artist closest to him through the words of encouragement, feedback, and meals he prepared for me that enabled me to experiment and create new work. His beloved grandfather, Tony Harrison, was an acclaimed poet and I think Ewan valued artists deeply as real people.

Since you live near the university where you and Ewan studied, were you able to reach out to people who had supervised his thesis while you were working on Borrowed Stories?

Yes, although not directly involved in the editing or publication process, all of the ITIA staff were so supportive and encouraging of the book, especially Ewan’s supervisor Professor George Corbett. We made sure to include Ewan’s PhD acknowledgements in which he thanks Prof. Corbett for his “consistently superb supervision and pastoral support” at the back of Borrowed Stories.

Editing another writer’s work can be complicated, even more so when it is a partner’s work. What were some challenges you did not expect as you worked on the book?

The most practical challenge was making out his handwritten notes for a few of the sections he had not had time to type and edit himself. For the rest, I had a good deal of experience editing Ewan’s work, so it didn’t feel very different to what I was used to. He was such a good writer, that working with him was always a copyeditor’s dream. As I mentioned, I took a really light-handed approach since he wasn’t present to accept or reject the suggested changes himself. I think it was the small decisions about how to organize, label, and arrange things and what to include in the brief editorial notes that I found difficult—I so wished I could have had just a 15 minute conversation with him to clarify how he would have chosen things to be presented. But, he trusted me and his family with the task and I think he would be proud of the result.

Did you find that you learned new things about Ewan as you re-explored his writing?

I don’t think I would say I learned new things, but I do think it deepened what I already knew. It was an interesting way to interact with his voice and be in a kind of dialogue with it even after he had gone.

While the book is about the artwork that Ewan explored for healing and education, you are also an artist who engages with classic artwork in various ways. What are some pieces of artwork that helped you to cope or find healing?

I have found films, TV series, and even fairytales about people being widowed or unwillingly separated from their partner to be quite comforting. The way Ewan interacted with art in facing his cancer diagnosis is very similar to how I have interacted with art in facing his death. C.S. Lewis’ A Grief Observed has been the most significant, but more popular examples would be the film Love Again and the TV series After Life. So much of the unbearableness of suffering is the sense of isolation and lostness that comes with it. It’s such a relief to know you’re not alone and to be given potential maps for how to navigate a path through grief (as Ewan well knew). I have also embraced Ewan’s defense of the sentimental and escapist qualities of popular art, and have enjoyed the therapeutic benefit of occasionally reading or watching what brings me comfort and offers a break from the pain of real life—the TV series Friends was one that Ewan and I turned to often for this reason.

I would also say the creative process of making art has been healing for me. Much of what I have created since Ewan’s death has incorporated words, ideas, and images from Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love. I have also been exploring the healing potential of movement and dance lately.

Fairly or not, anyone who has lost a partner to cancer tends to get asked immediately for advice or to be a listening ear when others receive a cancer diagnosis. What are some things you wish more people knew about partners of cancer patients?

This might seem obvious, but I’m still surprised by how much cancer feels a part of my identity although I never had it myself. Walking beside someone and caring for them during their cancer journey gives you a bit of a vicarious experience—when your other half has cancer, you sort of feel like you do too. Words like “MRI scan” and “test results” still give me a sensation of panic although those words have never been connected to anything life threatening in my personal health journey. It always feels strange to answer “no” when a doctor or health form asks me, “Any experience of cancer?”—because of course the answer in that context is “not at all,” but the answer that feels truest is “yes, lots.”

Currently, there is a short story by Ewan, “Half-Smile and Pinch-Face,” illustrated by you, available online. Do you have any plans to illustrate more of Ewan’s work in the future?

That project is very close to my heart. When we worked on that together, we didn’t expect that later that year he would be receiving a second round of radiation (repeat radiation to the brain tends to be avoided and treated as a last resort). So, I had not had the opportunity to witness any of the radiotherapy process that I later would, and was dependent on Ewan’s story and the descriptions he shared with me to depict the setting of his short story. Both that process and the themes of the story itself felt like going back into the past and enchanting a dark and despairing space. I’ve carried that idea with me, and have drawn Ewan over the last few years with that in mind—the sense that I can interact with and reframe the past through the creative act of illustrating it. However, this piece was sadly Ewan’s first and only attempt at creative writing. Attempting to illustrate his academic writing would be a challenge—but I wouldn’t rule it out!

Any upcoming creative projects you can share?

I would like to work on more folklore-inspired illustration this year. I think it would be great to find ways of connecting stories of contemporary individual’s real-life experiences with those of characters from regional folktales as a way of exploring the themes of connection and story-borrowing that Ewan experienced and researched and that I too have experienced in healing from his loss.

Borrowed Stories: Facing Cancer with Culture – from Breaking Bad to The Divine Comedy can be found at all major book retailers. More details about Karlee Rene Bowlby’s illustration work (Hireath Illustrations) can be seen on her website and on Instagram.